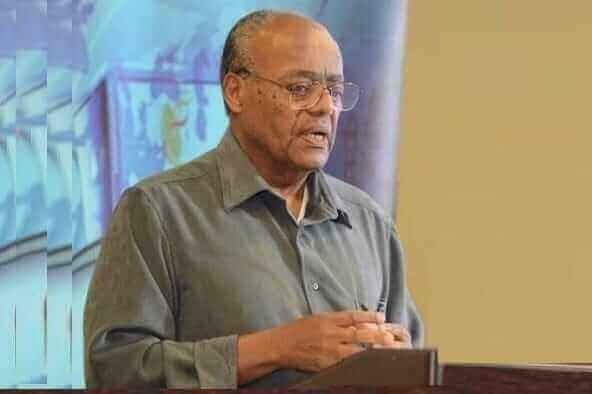

Paulos Milkias,

Paulos Milkias, an active participant in the student demonstration supporting the abortive coup d’état staged by Mengistu and Germame Neway in 1960, played a pivotal role in this historically significant event. The demonstration, directed towards La Garre station, demonstrated stark gendered separation, advising female participants deemed inadequate by the student leadership (though incorrectly!) to remain ensconced in the shadows of the Haile Selassie Theatre building. Upon reaching the precincts adjacent to the Moa Anbessa statue, the demonstrators encountered a formidable blockade erected by loyalist forces, strategically stationed in the 4th division military headquarters where prominent loyalists General Merid Mengesha and Kebede Gebre were located.

A tense atmosphere enveloped the area as a group of soldiers, armed with M1 rifles and displaying a threatening demeanor, faced off against the demonstrators supporting the coup. The seriousness of the situation heightened when a senior officer, holding a shotgun, gave a clear ultimatum, ordering the dispersal of the demonstrators within a mere ten seconds. As the countdown reached three, the possibility of violence became imminent; Professor Mesfin Wolde Mariam, the only Ethiopian faculty member among the demonstrators, urgently cautioned the students, foreseeing a potential tragedy if the confrontation continued. In the midst of chaos, the bold Vice President of the Students, Shibiru Seifu, openly defied orders and tried to break through the line, but was promptly stopped by Professor Mesfin, preventing a disaster. The group, miraculously unharmed, turned back, unaware of the false information spread by rebel factions from the imperial bodyguard, wrongly claiming that the students had perished at La Garre Station.

In another epoch-defining act, Paulos Milkias spearheaded a student delegation, endeavoring to petition the Emperor for the reinstatement of suspended colleagues during the academic year 1962-63. Amongst this cohort of impassioned activists stood Gebebyehu Firisa, serving as President, alongside the vociferously critical Yohannes Admasu, whose scathing denunciations of the prevailing political system echoed with profound resonance. Yohannes Admasu’s composition of ሰምና ወርቅ (“wax and gold” poetry), a revered tradition in Ethiopian literary discourse, delves into societal divisions with nuance. The interplay of “wax” and “gold” in this poetic form becomes a powerful tool for navigating the prevailing socio-political dynamics. At the heart of Yohannes’ verse lies an allegorical depiction of societal inertia and acquiescence, symbolized by the pervasive silence and perceived powerlessness of the populace against hegemonic feudal forces. As the verse resonates within Ethiopian society, it moves beyond mere aesthetic contemplation to become a catalyst for socio-political discourse and collective action. This politically charged stanza, rich in allegorical motifs, delves into metaphysical realms, exploring empirical questions and societal discontent with finesse. The allegorical journey of disillusioned youth, depicted through “wax,” prompts existential reflection, contrasted with the sharp critique of the entrenched feudal regime represented by “gold.” Through this dialectical lens, Yohannes exposes systemic injustices and unravels the complex web of oppression and terror ensnaring the Ethiopian populace.

This politically charged stanza, rich in allegorical motifs, delves into metaphysical realms, exploring existential questions and societal discontent with finesse. The allegorical journey of disillusioned youth, depicted through “wax,” prompts existential reflection, contrasted with the sharp critique of the entrenched feudal regime represented by “gold.” Through this dialectical lens, Yohannes exposes systemic injustices and unravels the complex web of oppression and terror ensnaring the Ethiopian populace. Here is the poem loosely translated into English:

Please unravel your secrets, you people from the dead,

How is the political system in your country led?

If you assess and analyze your compatriots’ plight,

Is their spirit burned out, or is it still shining bright?

Tell me who steers the reins of your economic growth,

Is it consigned to the scrap heap by the oligarchs you loathe?

Is your community tortured and tormented by oppression?

Are you clobbered with ridicule? Are you robbed of possession?

Do you shoulder a few people who wallow in riches,

Who exploits your labor and stash gold in niches?

Is conversing with the intelligentsia unpardonable and unwise,

Due to fear of assassins and entrapment by spies?

What about the mandarins of your civil service and government?

Are they insidious sycophants?

Are they deceitful and fraudulent?

Do you have in your land the uneducated citizen?

Who is beaten, who is hungry, who is enthralled and downtrodden?

Do you brave the night’s cold with nothing but rugs?

Do you sleep on a verandah infested with bugs?

Are there peons and serfs in the country of the dead?

Whose lives have been defiled by the landlords they dread?

Are they treated like cattle? Do they sleep without bread?

Do their children live on a pittance, and their masters overfed?

This is a very rough translation from Amharic by me. But I am not doing justice to Yohannes because the rendering doesn’t fully capture the power and poignancy of the poet’s Amharic ቅኔ (poetry). His work is deeply rooted in the unique cultural and historical context of Ethiopia, making it a significant contribution to the country’s literary and political landscape. Within his composition, the allegorical dichotomy of “wax” and “gold” emerges as a potent vehicle for exploring nuanced societal dynamics.

In this politically charged verse, the “wax” symbolically encapsulates the arduous journey undertaken by disillusioned youth into the metaphysical world of the “dead,” wherein inquiries of profound empirical significance are contemplated. This metaphorical expedition serves as a conduit for grappling with existential queries that elude resolution within the confines of a mundane “living” sphere. Conversely, the symbolic manifestation of “gold” embodies the poignant interrogation leveled by the same disenchanted youth, aimed squarely at the entrenched feudal regime.

The power of Yohannes Admasu’s poetry to ignite societal transformation is evident in the way it challenges the status quo and inspires the youth to question and resist Haile Selassie’s anachronistic feudal system. Through incisive inquiry, the poet lays bare the systemic injustices perpetuated by the ruling elite, which hold the Ethiopian populace captive within the shackles of ignorance, oppression, and terror.

Central to the verse’s thematic tapestry is its allegorical portrayal of ‘the dead’ as emblematic of societal inertia and acquiescence. This poignant metaphor underscores the populace’s pervasive silence and impotence in challenging the hegemonic dominance of a regime that consigns them to a state of perpetual servitude. The verse, conceived as an extended ‘wax and gold’ satirical stanza, is pivotal in galvanizing collective consciousness. Its recitation before tens of thousands of captivated Ethiopian spectators congregated during University College Day was an auspicious occasion that served as a catalyst for introspection and communal engagement. The poet was later a graduate assistant lecturer in the Department of Languages and Literature at Addis Ababa University and died in Harar under mysterious circumstances during the student ዘመቻ (campaign) while working with the peasants whose quandary he had eloquently championed in his poem.

In an additional episode, the students appointed Paulos Milkias and two other activists to go to the imperial court and appeal to Haile Selassie to rescind the suspension of the student president, Gebeyehu Firisa, and the poet, Yohannes Admasu, who were suspended following the above-mentioned provocative poetry reading. The team went to the then president of the University, Lij Kassa Woldemariam, and asked him to take them to the Emperor from whom they would ask for imperial pardon. Kassa expressed his willingness to advocate for the reinstatement of the suspended students by the Emperor, yet he delineated the constraints of his influence, emphasizing its confinement to the precincts of the campus. Implicitly, he conveyed a gleaming metaphor, likening himself to a custodian of a villa, charged with its maintenance and embellishment yet delimited by its boundaries, thus rendering him impotent beyond its confines. Despite his empathetic alignment with the students’ ethos and his pledge to safeguard their academic freedom within the scholastic enclave, Kassa cautioned against escalating criticism of the government and open dissent promoted beyond the realm of the campus, cautioning that such actions might undermine his capacity to intervene on their behalf in the event of their internment by the state. Following the encounter with Kassa, the delegates went to see the Emperor, who tried to cajole them by referring to the palace as “your house!’ He said, “in the future, when you have ideas to change things you disagree with, instead of blaring it to the public through political poetry, just come to the palace and tell us, and we will make any change necessary.” The Emperor then informed us that on compassion, the expelled students would be reinstated.

According to Paulos Milkias, another important episode occurred when the government, in a bid to quell dissent, revoked the boarding system under the presumption that the learners would be appeased by assimilating into the general populace of the capital, leaving him alone with politics which he considered his special preserve. In defiance of the policy, students organized a demonstration converging upon the citadel of the Negus near Meskel Square only to discover the absence of Haile Selassie. Undeterred, they staged a sit-in protest in front of the palace (known as the Jubilee Palace) strategically situated adjacent to Africa Hall, where African diplomats bore witness to the unfolding drama.

Amid this demonstration, Lij Kassa Woldemariam personally confronted me, attributing the organization of the protest to me He said in an angry voice . “ጳውሎስ፥ መች አጣሁ፦ አንተ ነህ ይኸን የምታደርገው!” I swiftly refuted this assertion, ascribing the protest’s spontaneity to the student body’s collective conscience, a veritable assertion validated by the circumstances. The confrontation was punctuated by the intervention of Lt. General Dressé Dubale, Commander of the Ground Forces, who came with a retinue of soldiers and told the student including me to go to the Menelik palace to meet the Emperor. In a brazen rebuke, President Kassa admonished the general, firmly asserting the autonomy of university and relegating military interference as incongruous. The general did not respond to Kassa’s rebuke, knowing full well his royal family status because he was married to the Emperor’s granddaughter.

Subsequently, the demonstrating students ignored Kassa and went to the Menelik Palace, where the Emperor awaited them. They were nestled within a protective cordon of the imperial bodyguard, armed with M1 rifles, live ammunition, and poised bayonets. On arrival at the imperial court, the bodyguard started intimidation by snatching a flag from the hands of a towering activist student, Baro Tumsa, who happened to be 6.6 feet tall. They smashed the flagpole into pieces and threw the three-color national standard on the floor. It was in this intimidating atmosphere that Haile Selassie announced the cessation of the boarding system, concurrently proffering a nominal monthly stipend of 50 Birr to defray living expenses, not hiding his disenchantment with the student demonstration, which he referred to as አድማ (conspiracy.)

When to justify the imperial decision, the President of the university’s Board of Governors, Lij Yilma Deressa, reminded the students that prominent Western institutions such as New York University do not have a boarding system, Vice President of Students, Iyesus Work Zafu countered that he was aware of that because as an exchange student in the U.S. he knew that New York University had no boarding system adding that that may be normal in prosperous societies like the U.S. where the per capita income of the people was several times higher that of Ethiopians. At that stage, the Emperor went into a temper tantrum and questioned the statistics quoted. He said Ethiopia’s per capita income is not less than that of the U.S.! He retorted, “Who will you compare Ethiopia with? Countries like Nigeria, Ghana, and Egypt? (For the information of the reader, at that time, the per capita income of the three countries mentioned by the Emperor was three times higher, and the Emperor himself knew it!) The message was actually to the uneducated masses at whom the live broadcast was aimed.

The Emperor accused the students of being selfish. He asked, “Do you want to monopolize the benefit alone?” He pointed out, “Look at the ministers serving in my cabinet at the moment. In earlier periods, “I had to cajole averse children from everywhere including the countryside and educate them, but now, times have changed. People know the advantages of Western education, and many children are currently waiting to be helped by us.” Here, Prime Minister Aklilu Habte Wold interjected and said, “It was thanks to his majesty that I and my brothers who were begging for food as ቆሎ ተማሪዎች (beggar students) were put through the modern school system by His Majesty that I have reached this rank.”

As a punishment for being insolent in front of the Emperor, Iyesus Work Zafu was denied his degree, though he won the Governor General Award as the best graduating student. Dean of students Dr. Aklilu Habte, on the threat of his resignation to the President, gave Iyesus Work his degree after the ceremony was over. The Emperor in the end indignantly reprimanded the students for exposing their country’s problems in front of strangers and retired to his office, still fuming.

Notwithstanding Haile Selassie’s plans to silence the students by shutting down the boarding system, they assimilated into the urban populous. They carried on their “conscientization” program, which the government security apparatus had observed and reported. The imperial government therefore belatedly learned that the action had backfired. Consequently, the Negus had no choice but to reinstate the boarding system within a few years.

Paulos Milkias also delineates other cases of tumultuous interaction between student activists and the imperial echelon, marked by a crescendo of dissent and authoritarian reprisal. There were several episodes that he helped organize and direct. The exigencies of the era compel a reassessment of power dynamics as the imperial edicts collided with the irrepressible enthusiasm of student activism. Amidst the backdrop of escalating tensions, the confrontation between student demonstrators and royal retinue unfolded in a dramatic tableau, punctuated by the intervention of formidable military forces and the imperial pronouncements of Neguse-Negest Haile Selassie.

In the crucible of dissent, ESM activists emerge as a vanguard, navigating the perilous terrain of political upheaval with sagacity and fortitude. Their indomitable spirit, epitomized by an unwavering commitment to social justice resonated as a beacon of hope amidst the encroaching shadows of authoritarianism. Through its activists’ impassioned advocacy and moral stance, the ESM embarked upon a transformative odyssey, catalyzing a renaissance of conscience and collective agency within Ethiopian society.

In this regard, Paulos Milkias was a leading activist for the momentous and transformative demonstrations of 1964-65 staged by university students, under the slogan “Land to the Tiller” and “Is poverty a crime?” Paulos was wounded and hospitalized in the Addis Ababa City police attack during the Shola Camps “is poverty a crime?” demonstration. The feudal regime then struck back. Its response was to mandate 50 lashes for persons convicted of a variety of actions, including insults, abuses, defamations or slanders of the Emperor, the publication of inaccurate or distorted information in any shape or form concerning judicial proceedings, the defense of a crime, spreading unsubstantiated rumors, false charges inciting or provoking others to disobey orders issued by the lawful authorities.

On the eve of the fall of the Aklilu Habtewold’s cabinet, the ESM members of the period, passed resolutions, calling for the boycott of classes and the staging of sit-in strikes and street demonstrations. The climax of all this in-campus flurry of activities and protest campaigns were the street marches and demonstrations during which students shouted slogans like “Down with the Haile Selassie government!” and chanted songs in which they glorified the achievements of, Ho Chi Minh, and Che Guevara They chanted: “Fānno tasamārā, fānno tasamārā, enda Ho Chi Minhi enda Che Guevara!”

ፋኖ ተሰማራ:

ፋኖ ተሰማራ;

እንደ ሆሺሚኒ:

እንደ ቼ ጔቫራ!

[“Oh, freedom fighters, Oh, freedom fighters organize yourselves and deploy in the fields like Ho Chi Minh and Che Guevara! (P.M.)

———————-

Tesfatsion Medhanie remembers that during Emperor Haile Selassie’s reign, the Ethiopian student movement (ESM) enjoyed a degree of tolerance from the government, despite engaging in activities, including uprisings, which challenged the status quo. The government’s response to student activism typically involved disciplinary measures rather than harsh repression, such as long-term imprisonment or extrajudicial killings.

Scholars such as Worku and Messay have offered plausible explanations for this phenomenon, but in our assessment, a crucial aspect remains overlooked: the pivotal role played by Lij (later Dejazmach) Kasa Wolde-Mariam, who served as the longstanding president of the University during that period.

I contend that Lij Kasa’s influence and interventions, often unseen by outsiders, were instrumental in safeguarding the rights of students and shielding them from unjust treatment by government security forces. A particular incident from around 1968 serves to illustrate this point vividly. a ceremony commemorating the donation of books to the law library by the French Ambassador, Lij Kassa articulated a nuanced stance that underscored the complexities of the student-government dynamic. He acknowledged the legitimacy of student concerns about national issues while emphasizing the importance of adhering to the law in exercising their rights. This stance positioned him as a mediator between the students and the government, earning him criticism from both sides.

In retrospect, it becomes evident that the tolerance extended to the student movement was intricately tied to the character, courage, and connections of Lij Kassa. As a member of the Royal family and a liberal-minded individual with a robust education, he possessed the confidence to challenge government authorities and prevent them from encroaching on campus grounds to suppress student dissent. Simultaneously, he maintained a stance of discipline and admonishment towards the students, a stance that was not always appreciated by the student body, who failed to fully grasp the challenges he faced.

In hindsight, it becomes apparent that Lij Kasa emerged as a guardian figure for the student movement, navigating a delicate balance between upholding student rights and maintaining order within the confines of the law. Despite our lack of understanding at the time, his contributions were indispensable in shaping the trajectory of student activism during that period.

The contest between Mekonnen Bishaw and Tilahun Gizaw in 1968 exhibited minimal engagement with the Eritrean independence question. Instead, it focused on divergences concerning the objectives and methodologies of the struggle. Mekonnen, the victor of the tournament, adopted a moderate stance, embodying traits of liberalism and reformism, particularly evident in his accentuation of participation in protest demonstrations in major Western capitals. Noteworthy elements of his discourse to the student populace included rhetorical questions such as “Have I not participated in the demonstrations in the streets of Paris!” Conversely, Tilahun epitomized the “revolutionary” candidate, espousing an unequivocally radical perspective on contemporary issues. Upon his successful re-election campaign in 1969, Tilahun remained steadfastly radical because in his inaugural address, he explicitly underscored the significance of “organized violence”.’

In the 1950s college students in Addis Ababa were reformists. Actually, they were basically reticent on matters political. The situation was to change in less than a decade. The students from other African countries sounded more advanced and forthcoming. In our view, the explanation for this lies in the fact that the residue of anti-colonial sentiment in those countries was still fresh. But their sentiment was merely nationalist. It was not an ideologically informed anti-imperialism. It thus dwindled and basically faded. The Ethiopian students on the other hand became increasingly ideologically inclined and made advances.

The ESM eventually professed Marxism-Leninism (ML). But there was no disciplined effort to study ML. Except perhaps for a few advanced individuals the students had only rudimentary knowledge of Marxist theory. But many of them regarded and called themselves “Marxist”. They were merely “baptized”! Thousands of them joined the struggle inspired by ML as they understood it and gave their lives. We sense a tendency to blame ML for Ethiopia’s predicament since the mid-seventies. This, it seems to us, is neither correct nor fair. On the contrary, the problem was that ML was inadequately and wrongly understood and applied. A correct understanding and application of ML was exactly what was needed.

The mention of the extent to which Emperor Haile Selassie’s regime was venerated – and thus tolerant – reminds one of a Marxist theory that was of crucial importance. And that is Antonio Gramsci’s theory of hegemony, which, as students we knew virtually nothing about. Gramsci’s theory of hegemony offers valuable insights into understanding the socio-political dynamics of Haile Selassie’s Ethiopia before its overthrow in 1974. The pervasive influence of the ruling class, coupled with coercive state apparatuses and ideological control, created a hegemonic order that marginalized and oppressed the majority of the population. However, resistance movements and counter-hegemonic struggles demonstrated the inherent instability of such systems of domination, ultimately contributing to the downfall of the Ethiopian monarchy and the emergence of the Derg.

Looking back, basic knowledge of the Gramscian theory of hegemony would have helped us understand that, in an important sense, Ethiopians had “consented” to Haile Selassie’s rule. HIM was after all the ‘Ecclesiastical Head of the Orthodox Christianity Church’, the paramount institution in the construction and sustenance of hegemony in the Ethiopian context. Had the Ethiopian students been enlightened on this Gramscian theory perhaps they would have chosen to pursue a more cautious, realistic and effective method of struggle for progressive change.

During the Emperor’s reign the Ethiopian student movement (ESM) was by and large tolerated. The government put up with student activities (including uprisings) without resorting to long-term imprisonment, let alone killings. Only disciplinary measures were taken in some cases.

Both Worku and Messay have offered explanations for this; and their explanations are plausible. However, in my opinion the most important explanation is missing. And that concerns the role of Lij (later Dejazmach) Kasa Wolde-Mariam, long time president of the University.

I believe Lij Kassa did a lot in ways not visible to defend our rights and protect us from being unjustly handled by the government’s security forces. I would like to recall one episode to substantiate this point. Sometime in 1968, the French Ambassador donated books to the law library. In this connection a ceremony was held at the office of Kassa Woldemariam to which I and my friend Fasil Abebe were invited by the Law Faculty Dean, Prof. Quintin Johnstone. The French Ambassador talked about how the students in France made trouble the year before. And Lij Kassa gave a reply whose substance as I recall was the following (words are mine):

Here too the students make trouble. But I am the one who is in the most difficult situation. On the one hand I tell the government authorities that just because one is a student, one does not renounce citizenship; and hence, it is understandable that our students are concerned with national issues. On the other hand, I tell the students that whatever rights they have, they can exercise them only in accordance with the law. I end up being blamed by both.

I believe he was quite sincere in what he said. In retrospect, I would say that we were tolerated to the extent we were because of the character, courage and connections of Lij Kassa. Related to the Royal family and a highly educated liberal, he was confident enough to challenge the authorities and prevent them from entering the campus to rough us up. At the same time, he had to admonish and reprimand us, which we resented of course. We had not understood how difficult his situation was. And hence we were not duly grateful to him. Come to think of it, Lij Kasa was indeed our guardian.

The contest between Mekonnen Bishaw and Tilahun Gizaw in 1968 did not seriously involve the question of Eritrea. The differences related more to the purpose and method of the struggle. In his approach Mekonnen – who won the contest – sounded moderate. He seemed to be a liberal and reformist when he emphasized his experience in the protest marches in Western capitals. Among the highlights of his address to the student body were those that comprised of rhetorical questions like “Have I not marched in the streets of Paris!” or something to that effect. Tilahun on the other hand was the “revolutionary” candidate. On the pertinent issues of the day, he expressed a viewpoint that was radical through and through. When he campaigned again in 1969 and won, he was equally (maybe even more) radical. In his inaugural address he was explicit on the importance of what he called “organized violence”.

In the 1950s college students in Addis Ababa were reformists. Actually, they were basically reticent on matters political. The situation was to change in less than a decade. The students from other African countries sounded more advanced and forthcoming. In my view, the explanation for this lies in the fact that the residue of anti-colonial sentiment in those countries was still fresh. But their sentiment was merely nationalist. It was not an ideologically informed anti-imperialism. It thus dwindled and basically faded. The Ethiopian students on the other hand became increasingly ideologically inclined and made advances.

The ESM eventually professed Marxism-Leninism (ML). But there was no disciplined effort to study ML. Except perhaps for a few advanced individuals the students had only rudimentary knowledge of Marxist theory. But many of them regarded and called themselves “Marxist”. They were baptized! Thousands of them joined the struggle inspired by ML as they understood it and gave their lives. I sense a tendency to blame ML for Ethiopia’s predicament since the mid-seventies. This, it seems to me, is neither correct nor fair. On the contrary, the problem was that ML was inadequately and wrongly understood and applied. A correct understanding and application of ML was exactly what was needed.

The mention of the extent to which Emperor Haile Selassie’s regime was venerated – and thus tolerant – reminds me of one Marxist theory that was of crucial importance. And that is Antonio Gramsci’s theory of hegemony, which, as students we knew virtually nothing about. At the risk of oversimplifying the concept, one can conceive of hegemony as leadership of a basic class – joined by other classes – not only in the economic sphere, but also in the social, political and ideological realms. It is related to and provides the context for legitimacy. A class or regime which is hegemonic enjoys the “consent” of those it rules.

Looking back, basic knowledge of the Gramscian theory of hegemony would have helped us understand that, in an important sense, Ethiopians had “consented” to Haile Selassie’s rule. HIM was after all the ‘Ecclesiastical Head of the Orthodox Christianity Church’, the paramount institution in the construction and sustenance of hegemony in the Ethiopian context. Had the Ethiopian students been enlightened on this Gramscian theory perhaps they would have chosen to pursue a more cautious, realistic and effective method of struggle for progressive change.

During the reign of Emperor Haile Selassie, the Ethiopian student movement (ESM) enjoyed a degree of tolerance from the government, despite engaging in activities, including uprisings, which challenged the status quo. The government’s response to student activism typically involved disciplinary measures rather than harsh repression, such as long-term imprisonment or extrajudicial killings.

Scholars such as Worku and Messay have offered plausible explanations for this phenomenon, but in my assessment, a crucial aspect remains overlooked: the pivotal role played by Lij (later Dejazmach) Kasa Wolde-Mariam, who served as the longstanding president of the University during that period.

I contend that Lij Kasa’s influence and interventions, often unseen by outsiders, were instrumental in safeguarding the rights of students and shielding them from unjust treatment by government security forces. A particular incident from 1968 serves to illustrate this point vividly. During a ceremony commemorating the donation of books to the law library by the French Ambassador, Lij Kassa articulated a nuanced stance that underscored the complexities of the student-government dynamic. He acknowledged the legitimacy of student concerns about national issues while emphasizing the importance of adhering to the law in exercising civil rights. This stance positioned him as a mediator between the students and the government, earning him criticism from both quarters.

In retrospect, it becomes evident that the tolerance extended to the student movement was intricately tied to the character, courage, and connections of Lij Kassa. As a member of the Royal family and a liberal-minded individual with a robust education, he possessed the confidence to challenge government authorities and prevent them from encroaching on campus grounds to suppress student uprisings. Simultaneously, he maintained a stance of discipline and admonishment towards the students, a posture that was not always appreciated by the student body, who failed to fully grasp the challenges he faced.

In hindsight, it becomes apparent that Lij Kasa emerged as a guardian figure for the student movement, navigating a delicate balance between upholding student rights and maintaining order within the confines of the law. Despite our lack of understanding at the time, his contributions were indispensable in shaping the trajectory of student activism during that period.

The election contest between Mekonnen Bishaw and Tilahun Gizaw in 1968 exhibited minimal engagement with the Eritrean independence question. Instead, it focused on divergences concerning the objectives and methodologies of the struggle. Mekonnen, the victor of the tournament, adopted a moderate stance, embodying traits of liberalism and reformism, particularly evident in his accentuation of participation in protest demonstrations in major Western. Noteworthy elements of his discourse to the student populace included rhetorical questions such as “Have I not participated in the demonstrations in the streets of Paris!”

Conversely, Tilahun epitomized the “revolutionary” candidate, espousing an unequivocally radical perspective on contemporary issues. Upon his successful re-election campaign in 1969, Tilahun remained steadfastly radical because in his inaugural address, he explicitly underscored the significance of “organized violence”.

In the 1950s, college students in Addis Ababa were reformists. Actually, they were basically reticent on matters political. The situation was to change in less than a decade. The students from other African countries sounded more advanced and forthcoming. In my view, the explanation for this lies in the fact that the residue of anti-colonial sentiment in those countries was still fresh. But their sentiment was merely nationalist. It was not an ideologically informed anti-imperialism in orientation. It thus dwindled and basically faded. The Ethiopian students on the other hand became increasingly ideologically inclined and made major advances.

The ESM eventually professed the world view of scientific socialism. But there was no disciplined effort to study the concept. Except perhaps a few advanced individuals the students had only rudimentary knowledge of scientific socialism. Notwithstanding this, many of them regarded themselves diehard scientific socialists. They were merely “baptized”! Thousands of them joined the struggle inspired by scientific socialism as they understood it and gave their lives for it. I sense a tendency to blame scientific socialism for Ethiopia’s predicament since the mid-seventies. This, it seems to me, is neither correct nor fair. On the contrary, the problem was that scientific socialism was inadequately and wrongly understood and applied. A correct understanding and application of scientific socialism was exactly what was needed.

The mention of the extent to which Emperor Haile Selassie’s regime was venerated – and thus tolerant – reminds one of a famous scientific socialist theory that was of crucial importance. And that is Antonio Gramsci’s theory of hegemony, which, as students we knew virtually nothing about. Gramsci’s theory of hegemony offers valuable insights into understanding the socio-political dynamics of Haile Selassie’s Ethiopia before its overthrow in 1974. The pervasive influence of the ruling class, coupled with coercive state apparatuses and ideological control, created a hegemonic order that marginalized and oppressed the majority of the population. However, resistance movements and counter-hegemonic struggles demonstrated the inherent instability of such systems of domination, ultimately contributing to the downfall of the Ethiopian monarchy and the emergence of the Derg.

Looking back, basic knowledge of the Gramscian theory of hegemony would have helped us understand that, in an important sense, Ethiopians had “consented” to Haile Selassie’s rule. Janhoy (Rasta Ja) was, after all, the ‘Ecclesiastical Head of the Tewahedo Orthodox Christianity Church’, the paramount institution in the construction and sustenance of hegemony in the Ethiopian context. Had the Ethiopian students been enlightened on this Gramscian theory, perhaps they would have chosen to pursue a more cautious, realistic and effective method of struggle for progressive change.(T.M.)

Part III, ESM Testimonials by Prof. Paulos Milkias and Prof. Dr. Tesfatsion Medhanie, composed under the title, Concluding Remarks will follow next.

Thank you both Professors Paulos Milkias and Dr. Tesfatsion Medhanie for gracing us with your accounts of and participation in the Ethiopian student movement going back to the early 1960’s. That was more than 60 years ago. I had the opportunity to witness the movement that was going on outside the country during my school years in the Middle East. My knowledge of the movement inside the country has been mostly based on hear and say accounts. This account by these two dear gentlemen will do its part to close the gaping hole for me. 60 years cover a long stretch of a historic period and put these two dear Horn of Africans in the same age group with me. What a blessing!!! I look forward to your next piece with great anticipation.

Blessings to you and your families.