By Nicholas Bariyo

Wall Street Journal

Three years ago, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed raised an army from the country’s militias to tame a rebellion in the northern region of Tigray. Now some of his allies are turning on him in what is shaping up to be an even bigger threat to both his leadership and the stability of one of Africa’s largest and most strategically significant countries.

The rift cracked open last November. A U.S.-brokered truce had ended the two-year civil war with the Tigray People’s Liberation Front, which had been fighting to carve out its own state in the north of the country. That cease-fire is still holding.

But members of a larger group of forces from the Amhara region that came to Ahmed’s aid are now vowing to overthrow him after his government moved to absorb them into the regular army. Worsening clashes are threatening to rip apart this core U.S. ally, long seen as a bulwark of stability in the restive Horn of Africa, and at a time when Russia has expanded its own footprint in places such as Sudan and the countries of the Sahel region.

Thousands of fighters have now joined a militia known as the Fano, ambushing forces loyal to the government in Addis Ababa, extending their control over Amhara in an attempt to preserve the region’s interests. The chief of Ahmed’s Prosperity Party in the region was killed in April in a brazen raid on his convoy, and dozens of officials have fled. Amhara’s regional president, Yilkal Kefale, stepped down in late August as the conflict worsened.

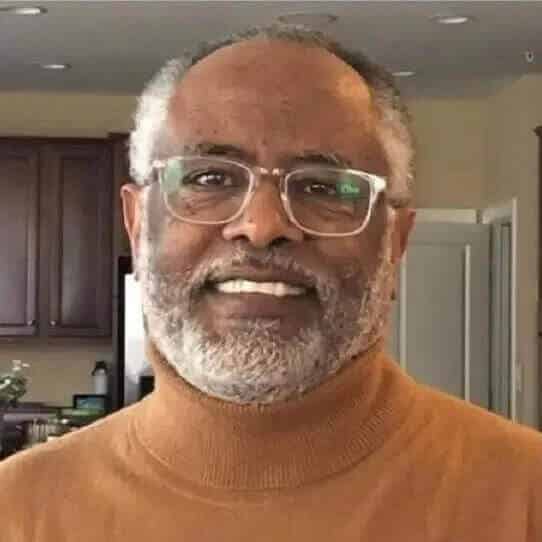

“Abiy Ahmed’s government seems to be losing complete control of Amhara,” says Yohannes Gedamu, an Ethiopian political analyst at Georgia Gwinnett College in Lawrenceville, Ga. “After the war in Tigray, Fano emerged more formidable and well-armed; fears of a more devastating conflict are not misplaced.”

Hundreds of people have been killed as the violence spreads. More than 600,000 have been uprooted from their homes in a country where 20 million people—about one in six Ethiopians—already are in need of food aid after a historic drought, while tens of thousands of refugees have poured across the border from neighboring Sudan, where two rival generals are battling for control in a bloody civil war.

Elsewhere, rebels in Oromia, Ahmed’s own home region, are also fighting to resist the former Nobel Peace Prize winner’s attempts to centralize control over the entire country.

The government’s response has been ferocious.

Troops have been redeployed from Tigray to launch a counteroffensive, backed by airstrikes and heavy artillery, according to activists and witnesses. They said a drone strike killed 26 civilians in mid-August in the town of Finote Selam. The government hasn’t commented. A spokeswoman for Ahmed described the Fano as an “armed extremist group” that is threatening public security. She said the government offensive, including a state of emergency declared on Aug. 4, is aimed at restoring order in Amhara.

Internet and phone lines have been severed while authorities enforce a night-to-dawn curfew. Hundreds of ethnic Amharas have been detained at police stations and camps across the nation, with lawyers and activists saying the brutal crackdown is now driving more recruits to the Fano, or “volunteer fighters” in Amharic.

“I am planning to join Fano to fight against this cruel government,” said one young man who spent a week in detention in July after being arrested while walking on the streets of Addis Ababa. “I just need to find a gun.”

Fano supporters say the government’s plans to disband the militia were misguided, and that they exposed the region to attack from Tigray or Oromia, its historic rivals for land and power in Ethiopia. Political analysts say it could crack open the fragile web of ethnic alliances and rivalries that define modern-day Ethiopia. Moreover, ethnic Amharas comprise nearly a third of the population—far more than the 6% who are Tigrayan—raising the stakes considerably.

“Abiy’s divide-and-rule policies to centralize power in Addis Ababa are failing,” said Zev Faintuch, an intelligence analyst with Virginia-based security firm Global Guardian, which offers emergency-response services in Ethiopia. “If this crisis persists, it will only increase public discontent against his regime.”

In recent weeks, Fano fighters have taken intermittent control of the airport in Lalibela, Ethiopia’s main tourist destination. They also raided the largest prison in the state capital, Bahir Dar, freeing thousands of inmates, including former militia members, government officials and activists said.

The fighting is generating growing international alarm. Israel has evacuated hundreds of its citizens along with other Jewish people, many of whom lived in Amhara. The African Union has warned that the conflict is chipping away at stability in an already volatile corner of the continent, while the U.S., which paused security and economic aid to Ahmed’s government, has advised its citizens against traveling to the region.

Domestic repercussions are mounting, too.

Amhara, around the size of Georgia, is the most fertile state in Ethiopia, producing the bulk of the country’s main staples, corn and sorghum. But the fighting has disrupted the supply of fertilizers, and now Amharas fearful of reprisals are arriving from other parts of the country, including areas of western Tigray where Amhara forces held sway during the civil war, often forcing ethnic Tigrayans off the land, according to Human Rights Watch.

As the influx grows, so too does the pool of the Fano’s potential recruits, activists say, creating a combustible situation in a country with increasingly few resources and a worsening problem for Ahmed, who won his peace prize in 2019 for ending a decadeslong border war with Eritrea.

For all his acclaim back then, said Gedamu, the analyst, “he has not promoted peaceful coexistence of his people.”

Write to Nicholas Bariyo at nicholas.bariyo@wsj.com

Two dangerous pieces of misinformation in this writing

1. “after his government moved to absorb them into the regular army.”

The move was not to absorb the regional force but to disband it as mentioned further down in the article. Still, it is immaterial whether they were absorbed into the Oromumma controlled regular army or the palace guard, what mattered was that the regional force was singularly dismantled in the midst of a threat to the existence of the Amhara and the people of the Amhara region.

2. The caption below the region falsely states that the “distribution of fertilizers was disrupted by the fighting in the region”. The fertilizer blockade or refusal was an intentional move by the government to engineer a famine in the Amhara region – a move that is part and parcel of Abiy Ahmed’s Oromumma plan to crush the Semetic block. The fertilizer refusal preceded Abiy Ahmed’s all-out war on Amhara.