By Solyana Bekele

By Solyana Bekele

Dubbing her the “Mother of Ethiopian Classical Music,”—as grand as that epithet sounds—might still be doing Emahoy Tsegue Mariam Gebru and her haunting, ephemeral, and አስተካዥ compositions a disservice. Born Yewubdar Gebru in 1923, by the age of six she went to Switzerland to study music. Though such prestigious educational journeys were not common among the Ethiopian public in the early 20th century, Emahoy Tesgue’s family was of the aristocratic stock that could afford just that. To be sure, her father was Kentiba Gebru Desta, mayor of Gondar.

Though Emahoy Tsegue demonstrated musical precociousness as a child, as an adult she felt her calling was in the service of her people, country, and God through the Orthodox Church. She joined the convent in 1944 but never quite gave up music; and for that, the people of Ethiopia and musicians the world over are eternally grateful. Within the Church, she earned her “Emahoy” title and continued with music through both piano and the violin—and even preformed for the Emperor Haile Selassie I on occasion.

Like genres and cultural productions that has the West at a loss, Emahoy Tsegue Mariam’s compositions defy categorization. It has been described as a meld of European classical music, but with the Ethiopian pentatonic scale—not quite jazz, nor was it ragtime. Her compositions break traditional musical conventions with no set tempo in any given song—slowing down or speeding up as the song calls for it, a marker of unearthly talent. She could go from 4/4 to 8/7-time signatures, and laymen would be none the wiser; the fluidity of her fingers over the piano make the sound she emits as natural as that of music that does follow traditional conventions.

Her “Souvenirs” album, recorded during the late 70s and mid 80s, and reissued this year, contains some of her most poignant and patriotic songs. In this album, Emahoy not only graces us with her quick-fingered, tempo defying piano but her pleading and ethereal voice as well.

Much like the ambiance of a turntable, when playing the first track, one hears the humming background before hearing her voice in “Clouds Moving on the Sky,” the first track in “Souvenirs.” (Though this can be because of the rudimentary recording equipment, it feels like one is in the room with her—especially with headphones in.)

Here, in exile, she longs for home. She sings, “የሰማይ አሞራ ፣ ልጠይቅሽ ወሬ/ ደርሰሽ መጣሽ እንደሆን፣ ከዉዲቷ ሃገሬ?” Her third track, “Is it Sunny or Cloudy in the Land You Live,” continues this theme, celebrating Ethiopia and the Blue Nile (Abay): “አባይን ተሻግሮ፣ አለወይ ሰማይ?/ሀገርስ አለወይ፣ ኢትዮጵያን መሳይ?”

No stranger to war or political strife, Emahoy Tsegue Mariam lived through some of the most turbulent periods in Ethiopian history. In the mid to late ‘30s, she and her family were prisoners of war during the Second Italo-Ethiopian war. She lived through both the peaceful and repressive eras of Haile Selassie’s reign, and the 1974 Revolution that established another repressive government of the Marxist-Leninist persuasion with Mengistu Haile Mariam and his Derg regime—not to mention the chronic famines the Ethiopian peasantry was systematically subjected to.

These moments no doubt permeated the music she composed and the lyrics she wrote. Though her music was not explicitly political for one side or another, her love of country and fellow countrymen/women clearly shone through. In “Ethiopia My Motherland,” she starts, “ኢትዮጵያ እናት ሃገር፣ ማንም አይደፍርሽም ” and greets civil servants, teachers, soldiers, and recognizes them for their service to country: “ሰላም ላንተ ይሁን የሃገሬ ምሁር/የምትታገለው፣ ሁሉም እንዲማር ።”

She bids those who leave their country for education to not forget their home: “ባህርን ተሻግረሺ፣ ለትምህርት የሄድሽው/ግዴታ አለብሽ፣ ሀገርሽን አትርሺው ።”

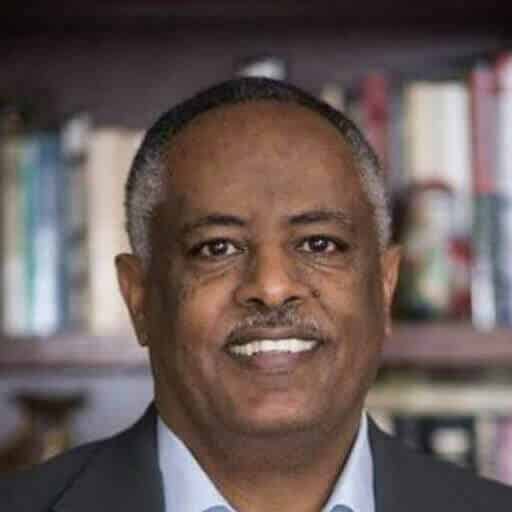

In many ways, this becomes a timeless call to all Ethiopians now living overseas for valid and varied reasons, to do whatever in their power to be of service—much like my “Ethiopia Tikdem”-coining grandfather’s call (Kebede Anissa) to journalists made a few years before his passing: that writers must “be committed to the development and unity of their country Ethiopia.”

Emahoy’s discography, particularly “Souvenirs,” bring salient questions to the fore to the Ethiopians today. What does love of country look like when countrymen slaughter each other with reckless disregard for the sanctity of life? What does service mean when medical personnel feel they’ll make more of a difference behind the barrel of a gun rather than with a stethoscope?

It’s hard to declare one’s love of country in one breath and shut one’s eye, or behold straight head, to the horrors committed with the other. It’s hard to say “despite and because of our differences, we are all Ethiopians” when every day that title and the rights that should come with it, become more and more elusive—if ever they were there to begin with.

But maybe because it is hard to say that we are all one despite our differences, it is precisely why we need to not only sincerely proclaim it but practice it as well. We, like Emahoy Tsegue Mariam are living through another moment in Ethiopian history where it feels like all is lost, like we are losing sight of what it means to be neighbors, to care for the fellow countryman or woman. But Emahoy’s Ethiopia is our Ethiopia. And if we care to embody the music she gave us, we should be radically loving our people, serving our people, and challenging every iteration of repressive governments that makes suffering a quotidian of Ethiopian life.

I’m sure the failed 1960 coup—the ensuing radical Ethiopian Student Movement, and the impending 1974 Revolution were moments of rupture that posed such existentialist sentiments to Ethiopians, then. Just like today’s violences pose the same questions to us today, both at home and abroad.

Like Maimire Mennasemay points out in his brilliant work, Qiné Hermeneutics and Ethiopian Critical Theory, liberation of both the individual and collective-kind (“አርነት”) comes partly with the practice of መደማመጥ–not just hearing but earnestly listening to one another and practicing unity in every pocket of our communities. For that is where Ethiopia is—in the way we treat and speak to each other every day. For if that remains, then the dream, and ensuing reality, of a truly united Ethiopia surely lives. The kind that speaks to power Emahoy Tsegue’s promise: “ኢትዮጵያ እናት ሃገር፣ ማንም አይደፍርሽም/በጀግና ልጆችሽ ታጥፘል ድንበርሽ።”