Michael Rubin

Michael Rubin

The current inquiry pertains to which additional nations may be susceptible to the same factors that contributed to the downfall of Assad.

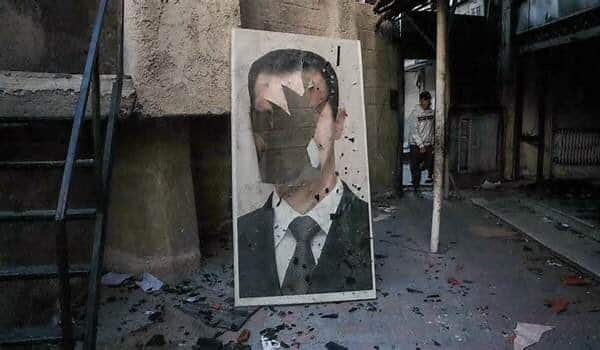

The Insight Other Nations Should Derive from Assad’s Downfall: Following over 13 years of civil conflict, the decisive military campaign leading to the fall of the Assad family’s 53-year governance in Syria transpired in under ten days.

There will be few who lament the end of Bashar al-Assad’s regime. Perhaps Western leaders such as former Secretary of State John Kerry, ex-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, or the late Senator Arlen Specter ought to have recognized that not all physicians educated in the West embrace Western liberal principles, as evidenced by the tyrannical reign of Papa Doc Duvalier in Haiti and Hastings Banda’s lengthy dictatorship in Malawi.

The departure of Assad has prompted a reevaluation of the circumstances surrounding his regime’s downfall. While it is often said that hindsight provides clarity, historians are tasked with interpreting events that have already transpired. The swift nature of Assad’s decline indicates that there are significant lessons to be gleaned from this situation. It is essential to recognize that the factors contributing to his downfall extend beyond the military actions of Israel against Hezbollah and Russia’s preoccupation with the conflict in Ukraine.

A critical aspect of Assad’s predicament was rooted in the inherent characteristics of his military forces. The structure and morale of his army played a pivotal role in his inability to maintain control. The challenges faced by Assad were not solely external; they were deeply intertwined with the internal dynamics of his regime’s military apparatus. This highlights the importance of understanding the complexities of military loyalty and effectiveness in the context of political stability.

In summary, the lessons learned from Assad’s exit underscore the multifaceted nature of political and military interactions. The interplay between external pressures and internal weaknesses reveals that a leader’s downfall can often be attributed to a combination of factors. As analysts reflect on this significant event, it becomes clear that a comprehensive understanding of both the military and political landscapes is crucial for predicting future outcomes in similar scenarios.

The Syrian Army operates as a conscript force. Before my initial visit to northeastern Syria over ten years ago to observe the de facto autonomous region established by the Kurds, I consulted with an American diplomat in Paris to determine the most pertinent questions to pose regarding American policy interests. At that time, one of the State Department’s primary concerns was the reason behind the Kurds’ failure to decisively confront the Syrian regime forces in Qamisli, the largest town under their jurisdiction, where the Syrian Army maintained control over a designated area known as “security square,” encompassing three unmarked blocks in the town’s center, along with adjacent locations such as the state bakery and the local airport.

The response from Kurdish leaders was revealing: the majority of Syrian soldiers were conscripts. They explained that if the Kurds were to launch an attack, the conscripts faced a binary choice: either engage in combat or surrender. Should they choose to fight, the Kurds would likely eliminate them, thereby diverting essential resources away from the more critical battle against Al Qaeda factions, particularly those associated with the Nusra Front, which was the precursor to the Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham group that recently played a significant role in the overthrow of the Assad regime.

On the other hand, if the conscripts opted to surrender, the Kurdish leaders cautioned that the regime would probably retaliate against their family members—fathers, sons, or brothers—who had been conscripted in areas such as Aleppo, Damascus, or other regions still under the regime’s control. This complex interplay of military strategy and familial loyalty underscored the difficult position faced by the Kurdish forces in their dealings with the Syrian Army.

For many Syrians, military service was viewed as a necessary obligation, albeit one that was relatively safe prior to the onset of the civil war. The preference among Syrians was to engage in conflict with Israel indirectly through Lebanon, as the front in the Golan Heights remained largely inactive for an extended period. Similar to the Egyptian military, a career in the Syrian armed forces could be financially rewarding, given the military’s significant influence over various business sectors. However, the pervasive nepotism and sectarian favoritism, particularly towards the Alawi community from which the Assad family originated, created significant barriers for the majority of Syrian Sunnis.

The outbreak of the civil war marked a turning point, leading to a severe economic downturn and a drastic decline in the living standards that Syrians had previously enjoyed. Although Syria was not among the wealthiest Arab nations due to its limited oil reserves, its agricultural sector provided more employment opportunities, with many Syrians engaged in farming or trade. The conflict, however, resulted in widespread displacement, which severely disrupted these livelihoods and exacerbated the economic crisis.

Corruption, which had long been a persistent issue in Syria, escalated dramatically in the wake of the civil war. The breakdown of social and economic structures allowed corrupt practices to flourish, further complicating the already dire situation for the Syrian populace. As the war continued, the combination of economic collapse and rampant corruption created a challenging environment for recovery and stability, leaving many Syrians in a state of uncertainty and hardship.

With Western powers remaining detached, Syrian forces successfully regained control of Aleppo. Although President Assad appeared to emerge triumphant in the civil conflict, the opposition still held onto small territories in northwest Syria and around Idlib, while the Kurdish factions preserved their autonomy. The expanded territory under Assad’s command should have theoretically provided a larger base for recruitment and conscription efforts.

Nevertheless, the ravaged economy rendered the Syrian currency nearly valueless, making it increasingly challenging for conscripts to support their families. This dire situation exacerbated corruption within the ranks, as Syrian soldiers resorted to theft to sustain their households or chose to go AWOL in order to fulfill their roles as primary earners. Consequently, the motivation for many Syrian troops to risk their lives for a dictator who lived in luxury while failing to address their fundamental needs was severely diminished.

The pressing question now arises regarding which other nations might be susceptible to similar conditions that could lead to the downfall of their leaders, particularly in light of the fact that Assad’s removal serves as a reminder that no dictator is invulnerable. The Islamic Republic of Iran stands out as a potential candidate. Iran operates two military forces, including a conscript army that is widely resented by the populace. Many Iranian families attempt to delay the registration of their sons to avoid conscription. With increasing protests and civil unrest, should Iranian Arabs choose to rise against the regime, it could lead to significant resistance among ordinary recruits. Additionally, disruptions to the Iranian oil trade could undermine the financial resources of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, potentially destabilizing the regime further, especially under the pressures of international sanctions.

Egypt presents a significant case in terms of military morale, which is nearly as dismal as the overall state of the nation. Within the Egyptian context, the military is perceived more as a commercial entity than a legitimate defense force. This situation creates a paradox, as the military’s control and manipulation of the economy exacerbate living conditions and foster public discontent. Although the Muslim Brotherhood’s own hubris and undemocratic tendencies contributed to its swift decline, President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi is mistaken if he interprets the Egyptian populace’s support for him as authentic; rather, it is a pragmatic choice, viewing him as the lesser of two undesirable options. Should the opposition in Egypt pursue reforms while the military persists in its corrupt practices, the nation may be on the brink of further instability.

Kuwait also faces potential vulnerabilities. It has been over thirty years since a U.S.-led coalition restored Kuwait’s sovereignty following Iraqi occupation. In recent times, this oil-rich emirate has receded from international attention, primarily due to its failure to keep pace with neighboring countries such as Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates in economic development. Despite Kuwaitis enjoying a per capita income exceeding $32,000, this figure remains less than half that of its regional counterparts. Concurrently, there is a noticeable increase in sectarian tensions, and the political landscape is becoming increasingly constricted.

While Kuwaitis may currently maintain the allegiance of their military conscripts, this loyalty should not be taken for granted. If the nation continues to tolerate extremist ideologies and fails to effectively manage its economy, the stability of the military and, by extension, the country could be jeopardized. The interplay between economic mismanagement and rising extremism poses a significant threat to Kuwait’s social cohesion and political stability, necessitating urgent attention and reform to avert potential stability, necessitating urgent attention and reform to avert potential crises in the future.

Azerbaijan could potentially face a collapse reminiscent of the situation in Syria. The nation has been under the rule of a father-and-son dictatorship for several decades, similar to the Syrian regime. Despite its apparent wealth derived from Caspian gas reserves, data from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund indicate that the average citizen in Azerbaijan experiences a lower standard of living compared to their counterparts in Armenia and Georgia. President Ilham Aliyev exhibits tendencies toward military aggression, paralleling the trajectory of former Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein. With limited political freedoms and deteriorating living conditions, it is conceivable that the Azerbaijani military might eventually rebel against the Aliyev family, particularly if such a move promises greater access to the nation’s resources.

The removal of Assad and the unfolding dynamics in the region could lead to the downfall of other long-standing dictators. The implications of Assad’s ousting may extend to neighboring countries, including Jordan, albeit for distinct reasons. Unlike Syria, Jordan does not maintain a conscript army, and its elite Special Forces are known for their loyalty to King Abdullah II, influenced by tribal affiliations. However, the king’s popularity appears to be greater internationally than domestically, as many Jordanians express dissatisfaction regarding perceived extravagance in the royal household. The support that Jordan receives from Gulf states mirrors the assistance that Russia provided to Syria, raising concerns about the sustainability of such backing in the future.

The geopolitical landscape is further complicated by Iran’s efforts to destabilize King Abdullah II’s regime through support for radical Islamist groups, alongside Turkey’s backing of the Muslim Brotherhood in Jordan. Additionally, the presence of Syrian Islamist factions along Jordan’s border adds to the challenges faced by the Hashemite monarchy. While Israel has historically intervened to protect the monarchy, the current reliance of Abdullah II on external support rather than a robust domestic foundation raises questions about the long-term viability of his rule. This reliance on foreign safety nets is not a sustainable strategy for ensuring a stable and prosperous future for Jordan.

Good riddance to Assad, though the whitewashing of the opposition is unwarranted. Still, what happens in Syria may continue in Syria. The Arab Spring started in Tunisia but claimed scalps in Egypt, Libya, and Yemen. Assad’s ouster and similar dynamics in some regional countries may soon claim scalps of other long-term dictators.

Michael Rubin is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, where he specializes in Middle Eastern countries, particularly Iran and Turkey. His career includes time as a Pentagon official, with field experiences in Iran, Yemen, and Iraq, as well as engagements with the Taliban prior to 9/11. Mr. Rubin has also contributed to military education, teaching U.S. Navy and Marine units about regional conflicts and terrorism. His scholarly work includes several key publications, such as “Dancing with the Devil” and “Eternal Iran.” Rubin earned his Ph.D. and M.A. in history and a B.S. in biology from Yale University.