Vol 64 No 17

24th August 2023

The rebellion in Amhara region and the government’s heavy response is testing the federal system to the limit

The rebellion in Amhara region and the government’s heavy response is testing the federal system to the limit

Initially, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed won plaudits for recasting the system inherited from his predecessor Meles Zenawi who dominated Ethiopian politics from 1991 until his death in 2012. Yet he may be haunted by one of Meles’ aphorisms as cited by British historian Alex de Waal: ‘Governing Ethiopia is like running in front of a volcano.’ For Abiy, the broad-based rebellion in Amhara region this year could prove to be just that eruption.

The Amhara nationalist militias taking up arms against the Addis Ababa government and its proxies are at least as perilous for Abiy’s grip on the shaky federation as the Tigray war from November 2020-2022. Then Abiy was able to corral a national coalition against the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF).

Now he has no such coalition to take on Amhara nationalists. His federal forces find themselves fighting Fano militias in Amhara, who had been key allies in the war against Tigray. And the numbers matter. Tigrayans are about 7% of the country’s population. About a quarter of Ethiopians are Amhara: they have dominated imperial and military regimes prior to the fall of the Derg in 1991, and have a powerful political and economic pressure group in the diaspora.

Amhara nationalists, mostly fighting with Fano militia units, have been spanning out across the region, building on grassroots support. Attempts by Abiy to bludgeon them into submission could backfire.

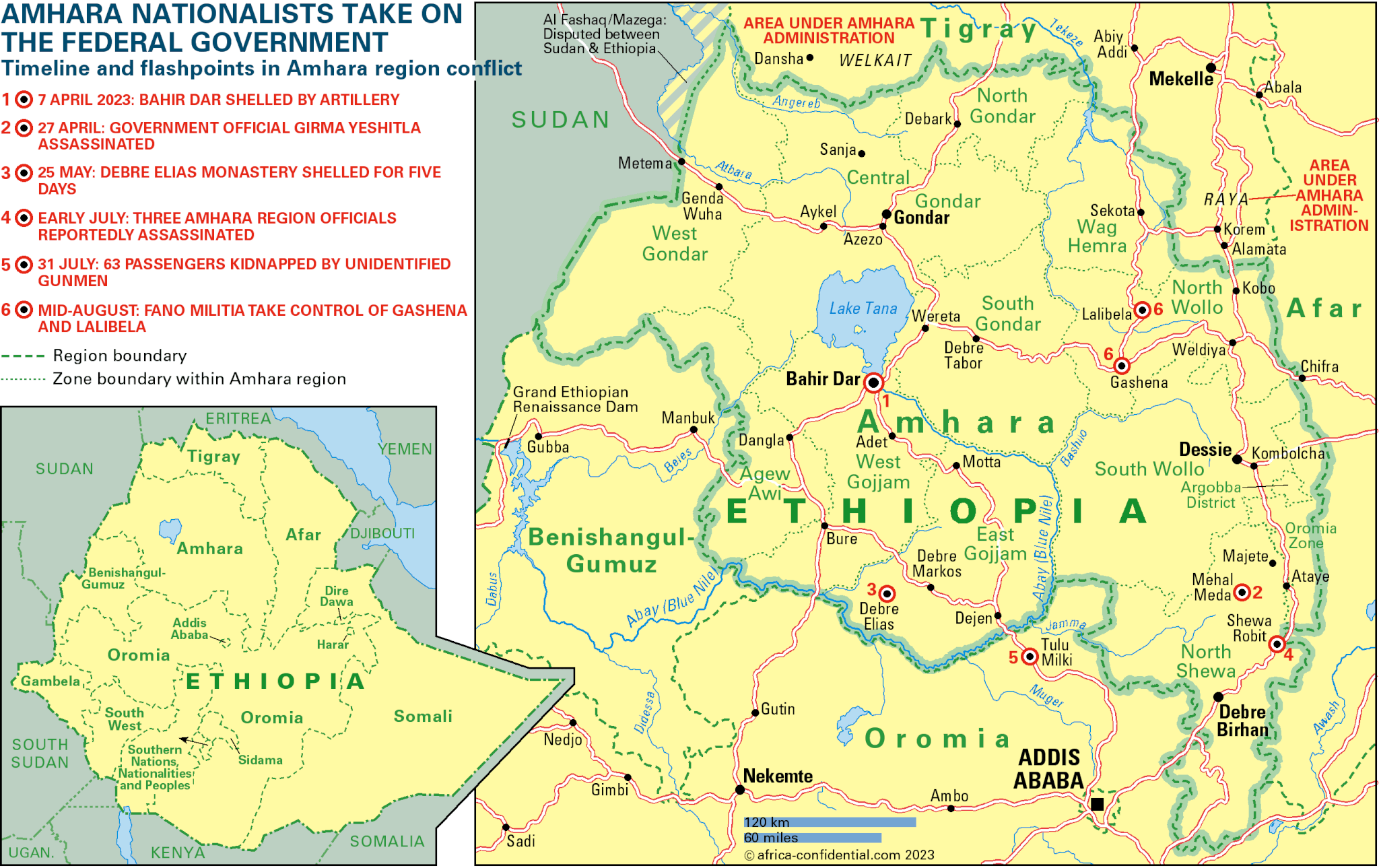

Reports of a drone strike by federal forces killing at least 26 civilians on 13 August in Finote Selam, a small town in the Amhara region’s West Gojam zone have stoked more resentment against Abiy. On 14 August, the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission spoke of reports of shelling in Finote Selam as well as in Burie and Debre Birhan, all in Amhara. It added reports that federal soldiers had been beating and killing civilians around Bahir Dar, the capital of Amhara.

Many dissidents in Amhara haven’t accepted Abiy’s leadership since he emerged as prime minister in 2018. Tempers have flared, periodically. The worst was in June 2019 when security chief General Asaminew Tsige tried to seize power in Amhara in a bid that killed the region’s president, several cabinet ministers and some security officers.

The latest upsurge in fighting triggered a request from Amhara region President Yilikal Kefale to the Addis Ababa government to declare a state of emergency in the region after Fano militia fighters had repeatedly clashed with federal forces. Ministers quickly acceded, arguing that ‘…the unlawful movement in Amhara, supported by armed struggle, has reached a point where it cannot be controlled through regular law-enforcement measures.’ This has meant sending in thousands of federal troops.

Amhara’s rebellion is proving difficult to defeat outside the region’s big cities. It is straining the shaky federation; complicating the peace deal that Addis Ababa signed with Tigray region last November (which ignored the Amhara-Tigray territorial disputes).

It has also ratcheted up tensions along the Amhara-Oromo regional border about a different set of territorial disputes, including control of the federal capital (AC Vol 64 No 4, How the Wellega war threatens Abiy).

Eritrea‘s offer of support to Amhara nationalists, seen as hugely provocative on the part of President Issayas Afewerki, could reignite conflict between the Asmara and Addis Ababa governments (AC Vol 60 No 14, Asmara and Amhara). Abiy’s recent statements about Ethiopia seeking access to the Red Sea (which it lost with Eritrea’s independence three decades ago) have reverberated in both capitals.

The heavy federal response has pushed back the Amhara rebellion in some towns and cities but the movement has been winning more support in the rural areas and among civilians across the country. In early August, Fano militia fighters seized control of the strategic Gashena town and historic Lalibela in Amhara’s North Wollo Zone.

The rebellion may accelerate the collapse of Abiy’s Prosperity Party in Amhara. Many junior party members and state officials seem more loyal to the Fano militia than the federal forces. By mid-August, cities and towns such as Debre Markos, Dejen, Debre Tabor, Shewa Robit and Debre Birhan (only 130 kilometres from Addis Ababa), were under the control of Fano fighters or threatened by them. Some areas of Gondar and Amhara’s capital Bahir Dar have fallen to Fano.

Calling in air and ground reinforcements, with curfews in place and de facto martial law, the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) is trying to retake areas it has lost, but with limited success. Flights to Lalibela, Dessie, Gondar, and Bahir Dar were cancelled but have now resumed. About 20 Spanish tourists were trapped in Lalibela but, according to Fano sources, they were kept safe in their hotel.

Deputy Prime Minister Demeke Mekonnen, from Amhara, wants a peaceful solution. Claiming that he understands that people’s expectations of Abiy’s premiership have not been met, he insists this cannot be rectified by war.

Fano fighters look unlikely to respond to calls for peace and negotiations. They want to drive all Abiy loyalists and federal troops out of Amhara. Discontent in Amhara spiralled on 1 April when the federal government said it would disarm all regional special forces across the country within a month (Dispatches 11/4/23, Prime minister Abiy presses ahead with national takeover of regional forces – despite mass protests). Ambassador Teshome Toga, Commissioner of National Rehabilitation in Addis, told diplomats that the 250,000-strong special forces would be disarmed, demobilised, and reintegrated into society.

The plan focused on Tigray, Amhara, Afar, Oromia, Gambella, Benishangul-Gumuz, and Southern Nations regions with the first round started in Tigray, Amhara, and Afar. Teshome costed the reorganisation at US$555 million, of which the government would finance about $120mn with foreign governments asked to provide the rest. Amhara’s insurgency will raise costs further.

On 6 April, Amhara’s regional government told the paramilitaries to hand in their guns and join the federal army or regional police. The disarmament included Fano and other Amhara militias which had fought alongside federal soldiers during the war in neighbouring Tigray.

The special forces demob plan faltered due to a lack of accountability and strong opposition from Amhara activists, especially in the diaspora. Some had supported the disarmament plan in principle accepting that ethnic-based regional governments should not be heavily armed.

But they objected to the timing in the wake of the peace accord with Tigray in November and the federal government’s failure to resolve the contested border areas, Welkait and Raya. Many Amhara argue these areas were annexed by TPLF in the early 1990s. They are still disputed but now they are under Amhara administration having been retaken during the war.

Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) fighters continue to attack and ambush in Southern Wollo and North Shewa zones of Amhara. Locals question why Oromia’s special forces seem to be excluded from the disarmament plan. Some official estimates put Oromia’s special forces at around 300,000 and the region’s authorities have been fighting a rumbling insurgency, again challenging the federal system.

The divide between the Amhara and the Oromo is growing sharply. Their activists offer contrasting versions of Ethiopian history and visions for the future. Those tensions could fracture Abiy’s Prosperity Party along ethnic lines; and that factionalism could rupture the federal armed forces. In early April in Amhara, objections to the plan to disband and integrate the region’s special forces triggered protests in Bahir Dar, Gondar, Debre Birhan, and Debre Markos, blocking roads to the cities.

Violence escalated when gunmen assassinated Girma Yeshitla, the General Secretary of the Prosperity Party’s Amhara branch on 27 April. Earlier he had admitted that around a third of Amhara’s estimated 100,000 special forces had refused to comply with the reintegration plan. Now their whereabouts were unknown. Sources close to the resistance say these well-armed and trained fighters have supercharged the grassroots militia units in Amhara.

Girma, who was central to the disbanding and integration of the special forces, had argued missteps by the taskforce commissioned to implement the plan had fuelled support for the resistance. On 27 April, Abiy said Girma was assassinated by Amhara nationalists near his hometown Mehal Meda in North Shewa Zone. This increased mistrust among Amhara who questioned the way Abiy prejudged the case before the police could investigate.

Then on 30 April, a Joint Security and Intelligence Task Force announced that 47 ‘terror’ suspects had been detained in Amhara. It said, ‘The suspects have been working together locally and in foreign countries to take control of the regional government to overthrow the federal government by targeting top officials in Amhara with assassination.’

Yet many of the suspects had been jailed before the uprising against the disbanding of the special forces was launched and prior to the killing of Girma.

Before protests started, the federal government had issued an arrest warrant for Fano members along with pro-Amhara journalists Gobeze Sisay and Mulugeta Anberbir.

The government also charged critical journalists such as Daniel Bekele and Mesay Mekonnen of the Ethio360 outfit. A moderate Amhara politician Lidetu Ayalew, currently in the United States has also been accused of plotting to overthrow Abiy.

Trying to justify this crackdown, government officials released what they claimed was an intercept of a phone conversation between East Amhara Fano leader Mihret Wedajo and Belete Gashaw. The recording, which appeared to implicate them both in the killing of Girma, was leaked on a pro-government website. A US-based audio and video forensic company said it was fake. Journalist Gobeze Sisay was arrested on 6 May in neighbouring Djibouti, supposedly with the support of Interpol, though Interpol denied this.

Fano militia based in the North Wollo Zone around the town of Kobo clashed with troops then agreed to hand over heavy arms but insisting on keeping their rifles. In Gondar, Fano strongly resisted disarming and residents surrounded military convoys.

After the army agreed to withdraw, the convoy was given free passage to return to camp. In Northern Shewa stretching from Debre Birhan in the south to Majete town in the north, federal soldiers clashed on several fronts with Amhara forces, resulting in heavy casualties.

THE POLITICAL FALL OUT AFTER AMHARA IMPLODEDPrime Minister Abiy Ahmed‘s efforts to disarm Amhara special forces have largely failed, forcing the regional government to try to govern from Addis Ababa. There is no consensus between Abiy and his Amhara deputy Demeke Mekonnen on how to proceed. Abiy and his generals want more military action. But in line with Demeke, Amhara regional President Yilikal Kefale wants to negotiate and tamp down the fighting. Abiy is also cracking down on Amhara businessmen, accusing them of supporting the rebellious Amhara special forces. On 26 April, the government froze the bank accounts of 35 prominent Amhara and two ethnic Afar businessmen. Tensions escalated after the government was accused of sending in mainly Oromo soldiers to disarm Amhara forces. In a sign of growing resistance, on 21 May, Eskinder Nega, award-winning journalist and ex-leader of Balderas party in Addis Ababa, launched the Amhara Popular Front to liberate the region and oust Abiy Ahmed. ‘Our struggle begins in the Amhara region but our goal is Ethiopia,’ added Eskinder. Four days later, the Debre Elias monastery in south-west Gojjam was attacked by troops who had intelligence that Eskinder was in the area. The historic monastery was shelled by artillery for five days. According to local sources, the government lost soldiers and hundreds of combatants were injured. Fighting intensified between Amhara rebels and the federal side in June and July. Amhara forces have embraced guerrilla warfare and are outflanking the federal forces. Since early June, militants have killed more than ten local party, government, and security officials, including the police chief of Debre Birhan. Yilikal fired three top security officials for failing to contain the unrest. Demonstrating the depth and breadth of the discontent, leading politician Yohannes Buayalew articulated Amhara grievances in the region’s council on 19 July. He demanded the council resolve the questions over Welkait and Raya: the two territories that Amhara claim as their own but which were seized from Tigray during the war. He blamed the federal government for denying a budget to these areas for over three years. He complained that Amharas were being politically and economically marginalised under Abiy. He said tens of thousands had been evicted from Addis Ababa. Amhara farmers have not received sufficient fertiliser during this planting season, increasing their sympathy for armed resistance, he added. Yohannes concluded by pleading to the leaders to facilitate negotiation between the Fano militias and the Amhara regional government. Such dissent is spreading internationally. Among the millions of Ethiopians in the United States, Amhara are rallying against Abiy whom they had backed when he came to power. A US-based Amhara movement is demanding Abiy’s resignation, calling for justice and accountability. Prominent community leaders are campaigning for sanctions against Abiy’s government. In a meeting in May with six senior Amhara officials, Abiy admitted the Prosperity Party has ceased to function in Amhara, with its middle- and low-ranking cadres in the region siding with the opposition. More devastatingly for the coherence of Ethiopia’s federation, Abiy warned that these political splits between regions could start to fragment the federal security forces. That, along with the opposition in Oromia and Tigray to the Addis Ababa government, must now count as one of the overarching threats to Abiy and his grip on the federal system. |

Africa Confidential

https://www.africa-confidential.com