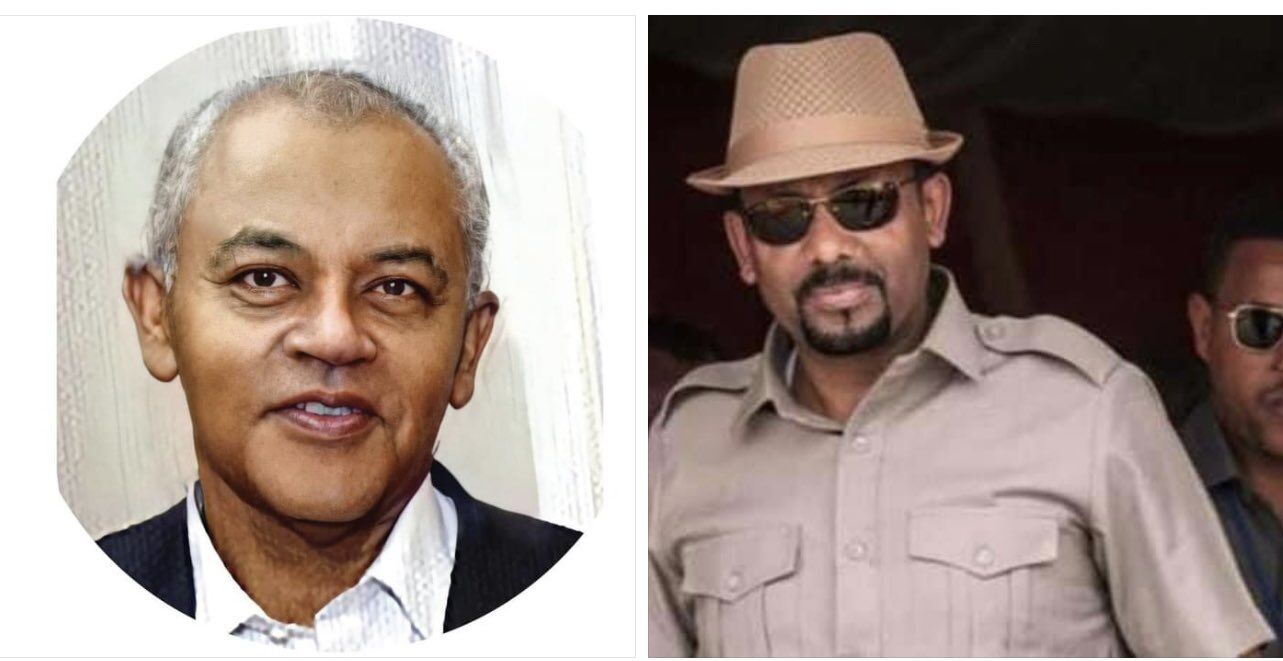

Tesfa ZeMichael

Confronting the most genocidal African Tyrant

The renowned historian Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD) once stated, “From Africa, there is always something new.” Pliny’s words hold true, as we witness the actions of Abiy Ahmed, the first and only Nobel Peace Laureate who actively engages in genocide and orchestrates a death squad known as the Koree Nageenyaa. If Pliny were aware of this, he would have surely advised future nominees to decline the Nobel Peace Prize, as it is forever tainted with the blood of innocent Ethiopian children.

Undoubtedly, Africa has witnessed the rise of numerous brutal dictators throughout its history. Among them, Jean-Bédel Bokassa (Central African Republic, 1966–1979), Francisco Macías Nguema (Equatorial Guinea, 1968–1979), Idi Amin (Uganda, 1971–1979), Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo (Equatorial Guinea, 1979–present), Hissène Habré (Chad, 1982–1990), Idriss Déby (Chad, 1990–2021), and Charles G. Taylor (Liberia, 1997–2003) stand out as particularly vicious and corrupt. However, when compared to Dr. Abiy, these dictators pale in comparison.

Abiy is the epitome of a Machiavellian dictator, surpassing any other Africa has ever produced. Unlike his monochromatic counterparts, he possesses a dual nature akin to Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. He effortlessly charms foreign visitors, holding their hands, while harboring an evil alter ego that callously drone-bombs innocent Amharas, Tigreans, and Oromos. In contrast, individuals like Ndindiliyimana committed genocide in Rwanda without any pretense. Dr. Abiy, on the other hand, carries out his genocidal acts under the guise of “law and order,” “prosperity,” and “democracy.”

The desire of all Ethiopians, with the exception of those benefiting from Abiy’s oppressive regime, is to remove him from power due to his genocidal actions. Currently, concerned Ethiopians are exploring the concept of a transitional government as a means of rescuing the nation from the political, economic, and humanitarian crises caused by Dr. Abiy. However, the idea of a transitional government poses several questions that must be addressed clearly in order for it to be viable. Extensive literature on transitional, provisional, or interim governments (these terms are used interchangeably in the literature) has been available since Talleyrand first introduced the concept in 1814.

The arduous road to a transitional government

There are several main categories of transitional governments. Type A refers to a Revolutionary transitional government, which is established after the overthrow of the existing government by the group that led the overthrow. Type B is a Power sharing transitional government, which results from an agreement between the existing government and the opposition forces. Type C is an Incumbent transitional government, which is created when the existing regime agrees to establish a transitional government as a new regime is being formed. Type D is an International transitional government, where the international community takes charge during the transition period. Type E is a Foreign power imposed provisional government, which is put in place after a military defeat, like the interim government in Korea established by the United States from 1945 to 1948.

There are two key concerns that emerge in this situation. The initial one pertains to the type of “transitional government” that can be realistically established within the current Ethiopian circumstances. The second issue revolves around whether the formation of a transitional government promotes the establishment of a democratic or an authoritarian Ethiopian government in the end.

It is highly improbable for Abiy to consider transitioning to a Type B or C government in Ethiopia due to his authoritarian grip on power and his Machiavellian, narcissistic, and sadistic traits. Moreover, the historical context and current circumstances of the country eliminate the possibility of Type D and E transitional governments, leaving only the A-type transition as a viable option. The proposal presented by the Congress of Ethiopian Civic Associations (CECA) seems to lean towards a Fanno-led A-type transition, which aligns with other suggestions for an A-type transitional government. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that the challenges associated with this type of transition in Ethiopia are substantial and necessitate careful deliberation. Abiy’s establishment of systems similar to Hitler’s Judenrat, particularly in the Amhara region, underscores his ruthless pursuit of power and control. Through the creation of an “Amhararat” in the Amhara Kilil, Abiy has effectively replicated the oppressive tactics of the Judenrat, consolidating power in each kilil using comparable methods. Despite facing resistance from the TPLF in Tigrai, Abiy strategically manipulates the situation by pretending to promote equality and loyalty, with the aim of involving the TPLF in his genocidal agenda against the Amhara region through deceptive tactics involving territorial disputes.

The formation of transitional governments has been a recurring phenomenon throughout history, with over a hundred such governments established since the Continental Congress in the USA during 1776-1781. However, only a handful of countries, including the USA, Australia, South Africa, Namibia, and some post-Soviet East and Central European countries, have successfully transitioned from these temporary governments to stable democratic systems. In contrast, the majority of transitional governments have resulted in the rise of authoritarian regimes, many of which have proven to be unstable over time. The outcome of a transitional government, whether it leads to political stability or instability, democracy or authoritarianism, is largely determined by the processes and substantive issues adopted during the transitional period.

Transitional governments that have managed to establish stable governance, whether democratic or authoritarian, often share a common characteristic – they are led by a dominant party rather than a coalition of equally powerful parties. This is primarily due to the inherent challenges and complexities associated with transitional periods. When a dominant party takes the lead, the transitional government tends to be more than just a transitional entity in name. A notable example is the Ethiopian “Transitional Government” of 1991, which was essentially a facade of transition. It was orchestrated and controlled by the dominant party, the TPLF, which utilized the transitional government as a means to consolidate its power by implementing an ethnic federation of Kililraete. Consequently, when the OLF attempted to resist the transformation of the Oromo Kilil into a Kililrata in 1992, the TPLF swiftly suppressed it through military force.

In order for the transitional government to effectively establish democracy, it is crucial that its structure and activities are founded upon the fundamental principle of citizenship, as exemplified by countries like the USA, Australia, South Africa, Namibia, and others. It is imperative to maintain coherence between the methods employed and the desired outcome. If democracy is the ultimate goal, then the process of attaining it must possess democratic elements at its core. Should the transitional government be organized based on ethnic identity, we would regress to the state of affairs in 1991 characterized by ethnic politics, inevitably leading to the recurrence of the unfortunate events witnessed over the past 33 years.

Transitioning from ethnic-based politics to citizen-based politics poses a significant challenge, especially in a country like Ethiopia where ethnic identity has been deeply ingrained for decades. The depoliticization of ethnicity is crucial for the success of a transitional government aiming to establish a democratic system. Without this shift, the content, process, and outcomes of governance are likely to be influenced by ethnic divisions rather than the collective interests of all citizens.

In the context of a multiethnic society, a transitional government must be led by a unifying political party or movement that prioritizes citizenship over ethnicity. When ethnic parties form coalitions to govern during transitions, it often results in political instability unless one dominant party exerts control over the others. This power dynamic can lead to authoritarianism, undermining the democratic aspirations of the population.

To achieve a truly democratic Ethiopia, individuals from diverse ethnic backgrounds must come together under a common citizen-based movement or party. This pan-Ethiopian organization should have both civilian and military branches, along with a decentralized yet coordinated structure. History has shown that such inclusive movements are effective in establishing democratic governance that represents the interests of all citizens, regardless of their ethnic affiliations.

The critical question arising from the aforementioned considerations is identifying the entity capable of spearheading the establishment of a movement or party dedicated to facilitating a democratic transition in Ethiopia. The Congress of Ethiopian Civic Associations (CECA) has put forth an intriguing proposition that involves a “Fanno-led negotiated settlement among armed groups to restore peace and security,” as well as a “Fanno-backed but independent and broadly representative national salvation council.” Nevertheless, the notion of a “Fanno-led” and “Fanno-backed” negotiation to form a transitional government may face resistance due to the three decades of vilification of the Amhara community as “oppressors,” “colonialists,” and neftegna.

One potential solution could involve adopting a non-ethnocentric approach, thereby deviating from the Fanno-centric strategy proposed by CECA, in the establishment of a pan-Ethiopian transitional movement and, subsequently, a pan-Ethiopian transitional government. Alternatively, there may be a need to explore the option of settling for a less ambitious goal: a negotiated agreement with Dr. Abiy that allows him to retain power while expanding the scope of democracy. However, given Dr. Abiy’s dark triad personality traits, the likelihood of such a compromise appears slim. Furthermore, even if Dr. Abiy were to agree to such a deal, it would entail maintaining the ethnic federation and the divisive 1995 Constitution, potentially reigniting ethnic tensions and perpetuating the conflicts and hardships of the past three decades.

I’m with Brother Tesfa ZeMichael’s call in this statement.

‘To achieve a truly democratic Ethiopia, individuals from diverse ethnic backgrounds must come together under a common citizen-based movement or party. This pan-Ethiopian organization should have both civilian and military branches, along with a decentralized yet coordinated structure. History has shown that such inclusive movements are effective in establishing democratic governance that represents the interests of all citizens, regardless of their ethnic affiliations.’

Everyone should be a stakeholder in charting the well being and future of that country including all current warring factions. Some times we have to bite our tongues to help further the accords for that gem of the colored and its noble people. No one is a foreign enemy to each other. With bigots and connivers side lined, those upright people know how to work and live together in peace and stability. They had shown their dexterity for that for centuries.

Let’s be peace mongers. Insha’Allah!!!