By Ashu Wasie

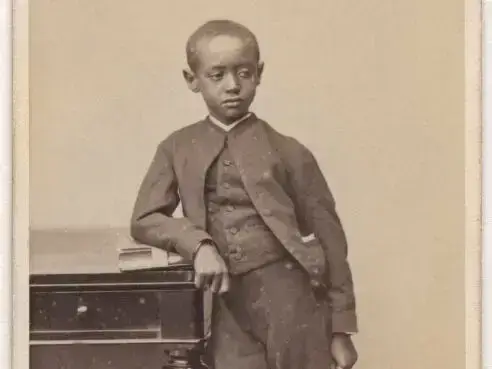

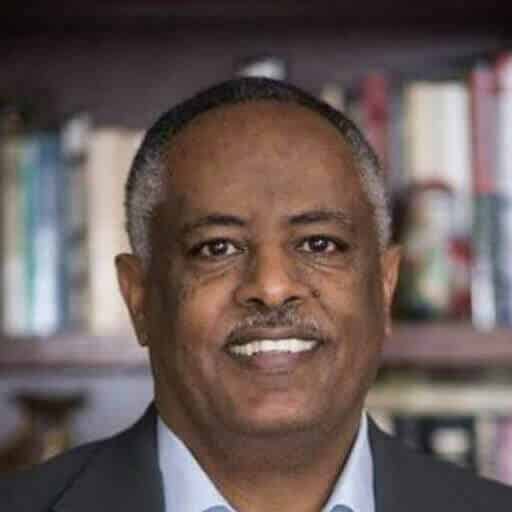

Professor Asrat Woldeyes was born in Addis Ababa on June 20, 1928. At the age of three, his family relocated to Dire Dawa in southeastern Ethiopia. When he was eight years old, Ethiopia was invaded by Italian Fascist forces under Mussolini’s rule. Tragically, his father, Ato Weldeyes Altaye, was captured and killed during the invasion after an assassination attempt on the Italian general Grazianni in Addis Ababa on February 19, 1937. Additionally, his grandfather, Kegnazmatch Tsige Werede Werk, was among the Ethiopian patriots who were deported to Italy and spent three and a half years there alongside other Ethiopian resistance fighters.

In addition to the unfortunate passing of his father, the future surgeon also had to endure the loss of his mother, W/o Beself Yewalu Tsige, who succumbed to grief after the untimely and brutal death of her husband. Despite being faced with a series of traumatic events at a young age, the future surgeon persevered in order to find his way and navigate through the chaos and uncertainty that arose from the sudden loss of his beloved parents. During a time when he needed their emotional support and parental guidance the most, he remained determined and steadfast. After the Italian fascist occupation forces were defeated in 1941, the future surgeon made his way to Addis Abeba to pursue his education.

In 1942, he enrolled in the esteemed Tafari Mekonnen School. He displayed exceptional academic prowess and was presented with a camera in 1943 for being the top student of the school that year. Following his time at Teferi Mekonen School, he was sent to Egypt to continue his education at Victoria College. Subsequently, he was dispatched to the UK, where he joined the Medical Faculty of Edinburgh University to pursue his studies in medicine. He was among the 42 Ethiopian students who were sent abroad during the post-liberation era. Unswayed by the allure of Western life, he promptly returned to his homeland upon completing his medical degree in 1956. After dedicating five years as a general practitioner at the former Prince Tsehai Hospital in Addis Ababa, he returned to Edinburgh, Scotland, to specialize in surgery.

He was the inaugural Ethiopian surgeon during the post-1941 era. Professor Asrat holds esteemed positions as a founding member of the Ethiopian Medical Association (EMA), a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of Scotland (FRCS Edinburgh) and FRCS (England), a member of the British Medical Association (BMA), the East African Surgical Association (EASA), and the International College of Surgeons (USA). Since his return to Ethiopia, Professor Asrat Woldeyes has rendered exceptional medical service to his country, both as a practicing physician and as a professor of surgery at the Addis Abeba University Medical Faculty, where he played a crucial role in its establishment. The medical school, which he later served as dean and professor of surgery, was established in 1965 as part of the Haile Selassie I university. II – The Disruption of Educational Development in the 1936-1941 Period – A Negative Legacy of Fascist Italy’s Occupation of Ethiopia. The occupation of Ethiopia by Fascist Italy resulted in the loss of an entire generation of emerging intellectuals. The Italian forces specifically targeted the few hundred Ethiopian intellectuals who had been produced prior to 1935, hunting them down and inflicting physical harm upon them, fearing that they would become leaders of the resistance movement against Italy. When the Italians finally withdrew from Ethiopia after an unsuccessful occupation lasting five years, there was a complete absence of an Ethiopian intellectual elite to oversee the modern administrative machinery and take on the responsibility of rebuilding the war-torn country.

Ethiopia had to wait for 12 years post-liberation to witness the first batch of graduated nurses, and another 14 years before the appearance of the first Ethiopian medical doctor, Professor Asrat Woldeyes. He was among the initial educated Ethiopians to emerge in a country where the loss of intellectuals due to the extermination by Italian fascists and their bandas created a significant manpower vacuum between 1936-1941. This forced Ethiopia to rebuild its educated elite from scratch. The country also had to rely heavily on expatriates for two decades after liberation, leading to negative impacts on decision-making processes and overall development.

The decisions regarding Ethiopia’s national developmental policies and priorities were often influenced by foreign experts, many of whom did not have Ethiopia’s best interests at heart. These “omniscient” expatriate experts played a significant role in shaping the country’s direction. Nowhere was their misguided influence more apparent than in the realm of public health. These experts advised against establishing a medical school in Ethiopia, a decision that had far-reaching implications. It meant that Ethiopia would continue to rely on foreign medical doctors, who faced language and cultural barriers when trying to communicate with the Ethiopian people they were meant to serve. In a field like medicine, it is crucial for medical professionals to have a deep understanding of their patients’ language, culture, and social background in order to provide effective care. By disregarding the importance of local expertise, these international experts hindered Ethiopia’s ability to address its own healthcare challenges.

Professor Asrat, along with a small group of Ethiopian professionals, faced numerous challenges in their quest to establish a medical school in Ethiopia. These obstacles were imposed by foreign expatriates who sought to impede or delay the process. However, Professor Asrat, a distinguished medical practitioner and professor of surgery, tenaciously fought against these barriers. In 1965, their collective efforts bore fruit as the first medical school in the country was established. Since its inception, this esteemed institution has produced hundreds of medical graduates.

The establishment of the medical school was made possible thanks to the unwavering dedication of medical professionals like Professor Asrat and his colleagues, including Professors Ededmariam Tsega, Paulos Quana’a, Nebiyat Teferi, Demisse Habte, and others. Through their commitment, the school of medicine has successfully trained numerous specialists in various fields such as surgery, internal medicine, gynecology and obstetrics, ophthalmology, and pediatrics. This remarkable achievement is primarily attributed to individuals like Professor Asrat and his few colleagues, who selflessly devoted their time to create national institutions that cater to the healthcare needs of the Ethiopian population.

It is indeed surprising that a national figure of exceptional caliber has been dismissed from the University, along with 41 other senior lecturers and professors, solely due to his political opinion. In today’s Ethiopia, where power seems to dictate what is right, former rebel leaders and societal outcasts have transformed into “all-knowing academics” who have the authority to judge, dismiss, and terminate independent-minded and “incorrigible” intellectuals at their own discretion. The current crackdown on intellectuals by the EPRDF government bears resemblance to the fascist regime in Italy, not only in its methods but also in its anti-Ethiopian objectives. The ruthlessness displayed in EPRDF’s actions exceeds that of the Chinese Cultural Revolution under Mao Tse Tung and Cambodia’s Pol Pot, as the latter were driven by communist ideologies that targeted intellectuals regardless of their ethnicity, whereas EPRDF’s campaign is fueled by ethnic animosity towards non-Tigrean Ethiopian intellectuals.

Professor Asrat’s dismissal from the Addis Abeba University medical school and teaching hospital in March 1993 was a shocking event. He had dedicated 38 years of his life to serving his country. During the Dergue Period (1974-1991), the decision-making process in Ethiopia was heavily influenced by ideology rather than practical considerations. The prevailing ideology of socialism took precedence over professional competence and merit. This ideological dominance even extended to the health sector, where inexperienced cadres attempted to revise the medical school curriculum and determine priorities for health manpower training without understanding the country’s actual health problems. Only a few individuals, like Professor Asrat, had the courage to challenge these ideologists. By opposing their misguided revisions, Professor Asrat was defying the sacred concepts of socialism and revolution that were deeply ingrained in Ethiopia during the mid and late 1970s.

Professor Asrat’s unwavering commitment to the national interest of Ethiopia led him to resist the blackmail and dictates of these cadres regarding the medical curriculum and health manpower training. In 1975, he addressed the eleventh Annual National Conference of the Ethiopian Medical Association (EMA) and spoke passionately about the importance of health manpower training in Ethiopia. He firmly stood his ground, refusing to yield to the pressure imposed by those who sought to control these crucial aspects of the country’s healthcare system.

It is regrettable that the crucial issue of health manpower training and medical curriculum in Ethiopia has been distorted by certain self-proclaimed intellectuals to deflect attention from their own failures and advance their personal agendas. By advocating for a quick-fix solution of training more health workers in a short period, these individuals are echoing the colonial mentality that prevailed in Africa. In the past, African individuals were limited to roles such as “medecine Africaine” or Assistant d’etranger in the French colonies, serving as paramedicals under the supervision of well-trained European doctors. Ironically, those who advocate for such practices in Ethiopia have no qualms about hiring foreign doctors regardless of their qualifications.

Professor Asrat and his few colleagues were labeled as “die-hard, conservative, bourgeoisie reactionary intellectual, etc” due to their principled stand on issues of national interest. This insult was endured by courageous individuals like him who defied an inept regime and system attempting to impose its own rules on the medical profession. In those challenging times, few Ethiopian professionals displayed such defiance, risking their careers and even their lives when opposing the dictates of ideologists and cadres. Despite current allegations, Professor Asrat was not one to blindly follow those in power, past or present. He consistently spoke his mind, unafraid of the consequences of his “defiant” actions. For further evidence of his commitment to truth, one can look at his confrontation with the Dergue over the circumstances of Emperor Haile Selassie’s death, as recounted by Professor John H. Spencer in his book “Ethiopia At Bay: A Personal Account of Haile Selassie’s Years”.

In 1980, during the height of the conflict in the northern region, Professor Asrat was assigned to the town of Mistswa. His duty there was to provide medical care to the casualties from both sides of the warring factions. However, the Tigrean elites who currently hold power in Eritrea and Ethiopia viewed Professor Asrat’s service in Mistswa as an act of collaboration with the former military regime, which was no longer in power after the EPRDF assumed control in Ethiopia. Consequently, Professor Asrat became the target of a relentless character assassination campaign orchestrated by EPRDF-controlled newspapers and magazines such as Efoyta, Maleda, Abiyotawi Democracy, Addis Zemen, the Ethiopian Herald, and others. In response to these baseless accusations in 1993, Professor Asrat firmly declared that:

According to the principles of medical ethics and the oath taken by every medical doctor, it is the responsibility of healthcare professionals to provide treatment to all individuals seeking medical assistance. As a medical doctor myself, I have had the privilege of treating notable figures such as the late Emperor Haile Selassie and the family of Mengistu Haile Mariam in the past. However, throughout my career, I have also dedicated myself to providing medical care to numerous impoverished Ethiopians who were unable to afford the cost of treatment. This commitment continues to this day, as I feel obligated to assist those less fortunate who find themselves in desperate need of my professional expertise. It is my duty to offer the best possible care and utilize my skills and knowledge to the fullest extent for anyone who seeks my help. Furthermore, if members of the current ruling groups (EPRDF/TPLF) were to require my assistance, I would willingly provide it, as it is my professional duty to treat and aid them, regardless of their political beliefs or affiliations. This excerpt, titled “Altruistic Service and Medical Ethics (1956-1993),” highlights the selfless nature of my medical practice and the ethical principles that guide my actions. Despite possessing extensive surgical skills and knowledge, Professor Asrat has never succumbed to the temptation of using his expertise for personal gain or to further his own interests. Unlike some medical doctors who establish private clinics solely to accumulate wealth, he has remained steadfast in his commitment to serving others. If he had chosen a different path, he could have easily become one of Ethiopia’s wealthiest individuals, but instead, he finds himself confined to the prison cells of Kershele in his old age. However, Professor Asrat is not driven by a desire for money or personal glory. He is a deeply religious and ethical surgeon who leads a modest, unassuming, and humble life. It is these altruistic qualities, along with his lifelong dedication to serving the Ethiopian people, that have earned him a revered and respected reputation among individuals from all ethnic and religious backgrounds who have sought his professional assistance from every corner of Ethiopia. His simplicity has endeared him to both his colleagues and his patients alike.

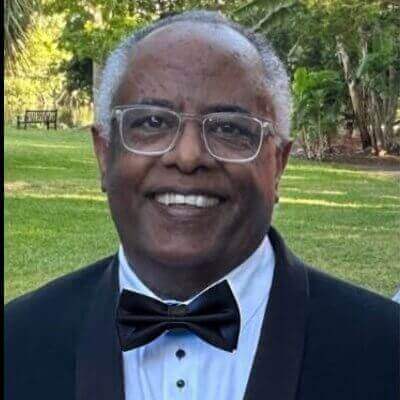

As a surgeon who has been going to Ethiopia for 12 yrs helping patients and training students/surgeons altruistically and as a surgeon who gave the Prof Asrat Keynote speech at the Annual Ethiopian Surgical Society meeting, I would like to echo your thoughts…