Simon Allison| The Guardian |

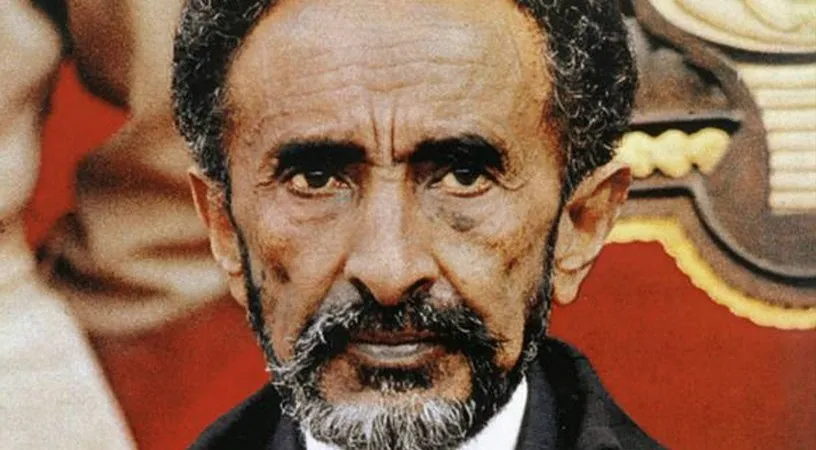

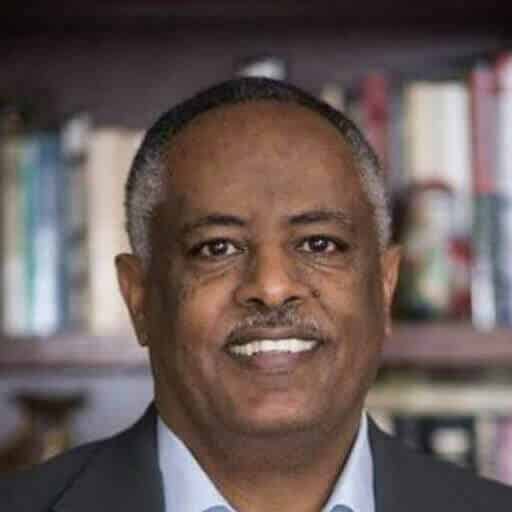

It is has been a little more than two months since the death of Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi. Since then, the country that he ruled over for 21 years has effected a remarkably smooth transition. His deputy, Hailemariam Desalegn, has taken over as both party leader and prime minister. There have been no major reshuffles. Policy changes, where they have happened, have been encouraging. Any threats to Desalegn’s succession were muted and, evidently, unsuccessful. Even the country’s restive Muslim population has been quiet, waiting to see what the new leadership is all about before pressing on with their campaign for a greater say in the country’s (and their own) affairs.

There is one problem, however. It’s minor in the grand scheme of things, perhaps, but raises a few nagging questions that Meles’ successor could do without. It’s also rather tricky to handle, even with the best of intentions.

Journalist Argaw Ashine explained the sensitive situation for Daily Nation: “The powerful widow of former Prime Minister Meles Zenawi is reportedly stalling on vacating Ethiopia‘s national palace for the country’s new leader and his family. According to government sources, Mrs Azeb Mesfin has ignored instructions to move to a new residence that would also be accorded full security detail. The government has given Mrs Azeb and her children the option of three residential villas in Addis Ababa but she is said to have refused to even visit any out of her own security concerns.”

Meanwhile, Desalegn and his family remain in their relatively small villa in a suburban area in the west of the capital. This is not particularly convenient for Ethiopia’s new head of state, although it does reveal his considerate side; he leaves for work very early in the morning and returns late at night in order to spare the already jam-packed Addis Ababa streets the further chaos that accompanies the passage of his convoy.

At a human level, it is easy to sympathise with the widow. Meles Zenawi was just 57 when he died, and her grief is real; the pair had been married for a quarter of a century. For most of that time, the couple lived in the prime minister’s residence in the national palace, as was their right. With Meles showing no signs of relinquishing power before his death, Azeb Mesfin would have envisaged many more years in what had become, in effect, their personal home. But losing her husband also means losing her home, a double blow which Azeb is probably not yet ready to face.

“For Azeb to leave a house she lived in for 21 years takes a lot longer than one might possibly imagine. Especially the properties of her late husband including his memorabilia, books, several of his precious possessions and other things might require time to be arranged and moved out of the house,” said Seble Teweldebirhan, an Addis Ababa-based reporter.

At a political level, things are a little more complicated (as they always are). Azeb Mesfin was no mere ornament to her husband’s immense power. She is a successful politician in her own right, and chairs an influential multi-billion dollar government fund for the rehabilitation of the Tigray region. Not coincidentally, most of Ethiopia’s political power is concentrated in the hands of people from this region (although not the new prime minister, it should be noted; he is from a southern province).

In her own way, she was just as powerful as her late husband. “She not just Meles Zenawi’s wife, but practically second-in-command of her husband’s tyranny. In fact, those who know her well say that she is very mean and more dictatorial than her husband,” wrote Abebe Gellaw, an analyst on an anti-government website. His view is jaundiced, but it contains an element of truth: Azeb and Meles were a team.

In fact, right after Meles’ death speculation began that his widow would manoeuvre herself into power. If true, she obviously failed, but perhaps this explains the strange delays in confirming Desalegn, the official successor, to the position. It also explains why she’s so reluctant to leave the official residence, the last vestige of executive power remaining to her.

For Desalegn, the issue is fraught. If he pushes too hard to get her out of the palace, he risks coming across as uncaring, potentially losing the support of Meles’ supporters. If he does nothing, however, he might come across as soft, and not in control – qualities that Ethiopians have not seen a leader for many decades.

This, perhaps, is no bad thing. Meles Zenawi’s obituaries were divided in their praise for his economic development policies and criticism for his repressive governance. If Desalegn can combine steady economic growth with a more enlightened, less restrictive government, he can really consolidate Ethiopia’s progress. And if can do that, then it doesn’t really matter how long it takes to get Azeb Mesfin out of the palace.