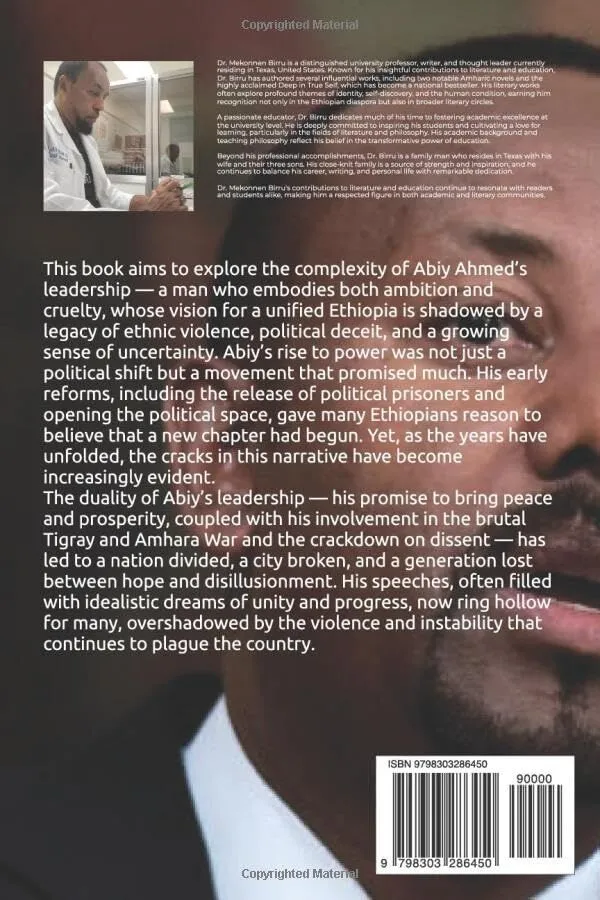

Aklog Birara (Dr)

February 4. 2022

“In broadening the debate about a country’s trajectory beyond the usual group of elite decision makers, national dialoguesoffer the potential for meaningful conversationabout the underlying driversof conflict and ways to holisticallyaddress these issues. There is a risk,however, that national dialogues can be deliberately misused by leadersseeking to further consolidate their grip on power.”

United States Institute of Peace

Part II

Experts around the world share a common definition on national dialogue. I shall use a definition by Katrina Planta, Vanessa Prinz and Luxshi Vimalarajah in “Inclusivity: guaranteeing social integration or promising old order hierarchies,” Berghof Foundation. National Dialogue is an “attempt to bringtogether all relevant national stakeholders and actors (both state and non-state), based on a broad mandate to foster nation-wide consensus on key conflict issues.”

The African Union used this same definition in Volume 3, Managing Peace Processes: towards more inclusive processes, 2013. But the transformative values of inclusion and participation: representation, legitimacy, relevance, power balances and societal ownership offer both opportunities for ultimate success and challenges that may derail the process entirely. That is to say that not all national dialogues are successful. Transparency, honesty, integrity, selection criteria, code of conductfor the Commission as well as for stakeholders and clear definition of the ultimate objective of the dialogue matter.

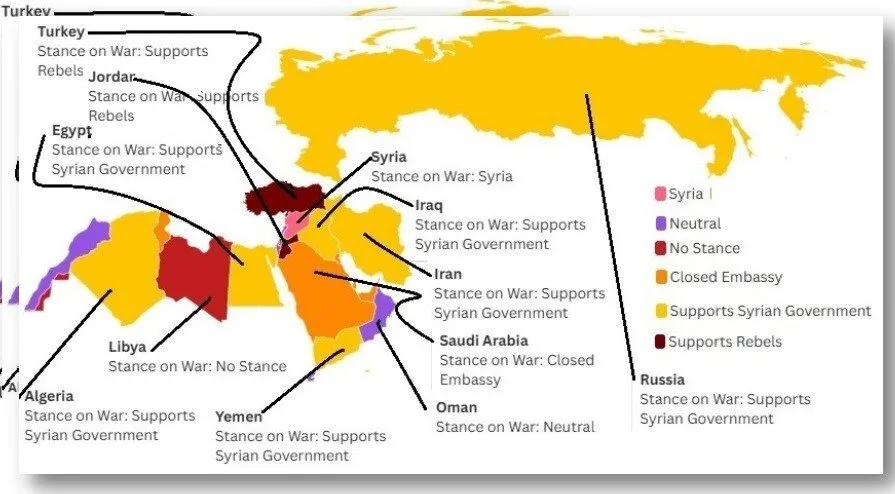

For example, in Yemen, still at war, National Dialogues involved more than five hundredparticipants. In Afghanistan, another conflict ridden and failed state, more than 1,000 Afghansparticipated. In both cases, political actors failed to empower dialogue participants to make hard political decisions. Instead, they charged participants to serve as passive and neural facilitators.

In South Africa, a model of success, the preparatory phase involved fifty organizations and 120 representatives. Women, youth, faith, and business groupswere heavily involved in the process that received and reviewed 22,000 statementsfrom victims of political violence.

In Egypt, the military dominated the dialogue process. In Mali, the transitional government at the time appointed 1,500 Commission representatives. In the DRC, 362 delegates were involved. In Somalia, 150 voting clan members representing the entire country were involved.

Review shows that there are successful and not so successful Commissions for peace and reconciliation.

My thesis for this commentary is as follows. The ultimate objective of national dialogue for peace in Ethiopia is to deal with the root causes or the “underlying drivers” or the elephant in the roomthat triggers perpetual civil conflict, political violence, and mayhem.

The hottest policy matter in Ethiopia today

Today, the hottest policy matter among Ethiopian political and social elites, intellectuals, scholars, civil society, government officials and the international community is the National Dialogue for peace, reconciliation, and national consensus. Unfortunately for the country and its 120 million citizens who deserve peace, stability, and a sense of shared humanity,Ethiopia’s ethnicized politics affects this honorable process adversely. Observers also allege that the peace process is top down.

I am not yet ready to conclude that the process is hard wired and likely to be “deliberately misused by Ethiopia’s leaders to consolidate their grip on power.” In a country with weak national institutions, it is not farfetched this may occur.

Peace that comes from unfettered commitment to human security to life is a human need. So is access to adequate food, safedrinking water, health services, shelter and ideally, electricity. To enhance legitimacy and ownership, inputs to the process through horizontal linkages seeking inputs from a cross-section of ordinary citizens proactively as well as from intellectuals and scholars alike must be encouraged patiently and deliberately. The tone and intensity of discourses concerning the criteria, composition androle of the Commission approved by Ethiopia’s Parliament must demonstrate a level of civility, moral, ethical, intellectual maturity, transparency, and integrity that in turn augurs well for the success of the Commission. An ethnicized and politicized processwill result in a jaded outcome.

Adversarial tendencies are deeply rooted in Ethiopian political and social culture, prominently among political and social elites, intellectuals, and scholars. Inflexibility in mind set among Ethiopia’s learned class impacts even this most honorable process and march for national peace and reconciliation. If one is unable to tone down combustible rhetoricand reconcile differences among intellectuals, scholars, and other members of the learned class, how is it possible to expect the evolution of a peaceful, mutually respectful and rules- based Ethiopian society?

I genuinely believe that critical inputs to the national dialogue agenda from a cross-section of civil society, ordinary citizens (specially women and youth) affected by conflict and war, intellectuals and scholars as a group or in their capacity as induvial Ethiopians with vested interest in their country’s future; rather than as ethnic identity influencers and status seekers and or political power grabberswould go a long way in making the process dynamic, open, transparent, trusted and credible.

This takes me to the role of Ethiopian intellectuals and scholars. If Ethiopia is lucky enough to possess a collaborative if not a unified groupof intellectuals and scholars with a compelling and an all-inclusiveplatform to serve the common good, we would have an unassailable power as influencers. This social group would serve the common good. I believe it still can. But it must first change its paradigm ofthinking. It must learn to unlearn. It must embrace Ethiopia as a country; and Ethiopiawinet as a common and binding identity. I say this because ethnic identify has failed Ethiopia.

Let us agree on the context. Ethiopia is still at war. The government of Ethiopia caved in to “pressure” from the Biden Administration and released terrorists. As a community, Ethiopian intellectuals and scholars have not expressed a unified view one way or the other. We-Can is the only assembly of Ethiopians that I am aware of that contested the decision to release terrorists. It forewarned about unintended consequences. Releasing terrorists and making side deals with the TPLF could potentially compromise Ethiopia’s territorial integrity, cause a major civil conflict again and break-up Ethiopia. The current insurgency by the TPLF targeting the Afar and Amhara regions illustrates this point. This leads me to the question “What core or fundamental policy matters(among multiple demands) that trigger political violence should Ethiopian intellectuals and scholars choose, champion and advocate in the spirit of serving the common good?

The cost of war

I go back to Einstein’s wise advice “If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutesthinking about the problem and five minutesthinking about solutions.” We Ethiopian intellectuals and scholars often fail to diagnose and understand the problem fully.

A broad assessment of the disastrous aftereffectsof the war in Tigray, started by the TPLF 15 months ago is a legitimate starting point. I admit that a complete inventory of human atrocities and socioeconomic costs has yet to be done. Preliminary findings are staggering. In the Amhara region, the TPLF looted, damaged, or destroyed forty hospitals, 453 health posts, 1,850 public and 466 private clinics, fourblood banks, one oxygen plant, one health college and fifty-five ambulances. It looted,damaged, or destroyed hundreds of schools. The looting and destruction of Mekdela Amba University illustrates the level of brutality inflicted on the country’s youth. Therefore, the atrocities and destructions pose multigenerational risks for Ethiopia.

The TPLF and OLA/Shane are deliberate in targeting not only persons; but also, the primary sources of economic and social infrastructure that support local people. For example, the TPLF vandalized; and destroyed the ultra-modern Roha hotel, in the spiritual icon of Lalibela. Rohaemploys large numbers of local people. It is no more!

In the Afar region, thirty mosques, fifty-seven health facilities and 759 schoolswere either severely damaged or destroyed. Imagine mosques that serve as places of worship being targets and attacked. Imagine farm animals identified as targets and bulleted. Imagine an 80-year-old woman raped because of her ethnic identify. There is no accurate number of non-combatants summarily executed in the two regions. It is in the tens of thousands. The number of female children, girls and women raped by TPLF combatants in the two regions exceeds one hundred.

The TPLF is not the sole operator of political violence in Ethiopia. BBC Africa quotes the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC), a government entity this week that Ethiopian security forces in Oromia massacred fourteen civilians and local leaders last December and left their corpses in a forest. Wild animals ate the corpses. “Dubbed the “Karayu massacre” – named after the location of the attack – the report says the victims were taken from their homes to a nearby forest by the security forces and shot.” Such massacres of innocent civilians have become too common in Ethiopia.

In an informal conversation with a confidante, Sebhat Nega, a member of the TPLF terrorist network released by the government of Ethiopia dismissed as immaterial ethnicity-based atrocities committed by his party in the Afar and Amhara regions. He is quoted saying, “What difference does it make if the TPLF massacres 10,000 innocent civilians?Mind you, in China, they massacre one million.” This normalization of abnormalitiesin Ethiopian society based on ethnic identity is among the “elephants in the room”that the peace process must address head-on regardless of the victim or the perpetrator.

I agree with BBC Africa, EHRC, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, the Committee to Protect Journalists and others that “Reports of extrajudicial killings have increased in Ethiopia particularly following the outbreak of war 15 months ago in the country’s north,” but also in Beni-Shangul Gumuz, West Wellega in Oromia and other sites.

In the Amara region alone, the agricultural sector on which most Ethiopians rely to support their livelihoods is the sector that suffered the most with an estimated cost of 466 billion Birr. The TPLF looted, damaged, or destroyed electrical grids and stations and telephone lines worth billions of Birrs.

The human toll is staggering: three (3) million civilians displaced. In a country where ethnicity-based massacres and displacements are recurrent, you may ask “So what?” So, what if the TPLF or OLA/Shane massacres tens of thousands? So, what if millions die of starvation? I do not believe this is normal at all.

The above samples do not give us a total picture of the trouble Ethiopia is in. What about atrocities including rapes and socioeconomic and infrastructural destruction in Tigray. If you agree with me that we must discuss Ethiopia holistically;then accounting and accountability for human atrocities, and economic destruction must be all inclusive. Otherwise, an inclusive process becomes incomplete.

I urge Ethiopian intellectuals and scholars to set aside minor differences and conduct a comparative assessment of the level of human atrocities and economic destruction executed by the TPLF on the Afar and Amhara population in the past 7 months; and compare the same set of atrocities and destructions that occurred in Bosnia, Iraq, Kosovo, Libya, Syria, and Yemen combined. My preliminary assessment tells me that TPLF atrocities and destructions far exceed any other in living memory. It is important to do this so that similar occurrences will not happen.

This leads me to the question of “Whether it is prudent for the government of Ethiopia to set aside these staggering atrocities and destructions and release TPLF and other terrorists under the pretext of restoring peace and stability in Ethiopia?” My response is that such an approach is flawed. Ethiopia must not allow the TPLF or OLA/Shane to get away with murder.

I try to understand the incessant pressure imposed on Ethiopia by the Government of the United States. This pressure must not, however, undermine Ethiopian government policy of mobilization to defend Ethiopia’s sovereignty, territorial integrity, and the security of its 120 million citizens. The war against the terrorists TPLF and OLF/Shane is a national struggle for survival. It is not an Afar or Amhara matter. The release of Sebhat Nega and his colleagues for any reason including age and health status puts into question why Ethiopia expended the lives of tens of thousands and spent tens of billions of Birrs for a war whose end goal may be submission to demands by the TPLF and its Western allies led by the USA?

Ethiopian intellectuals and scholars as a group have a moral and ethical responsibility to opine on the above and other substantive policy matters that bedevil Ethiopian society. Their capacity to leverage their expertise in advancing the common good depends in large part on their readiness and willingness to work together as Ethiopians.

Below is a set of hard-core policy and structuralquestions thar require immediate attention. I am convinced that thinking and working together as Ethiopians, they (we) can impact the imminent dialogues in Ethiopia positively. The Ethiopian people deserve a common approach to justice, truth and peace from the country’s intellectuals and scholars regardless of where they live.

- What are the root causes that trigger political violence in Ethiopia? Is it a political leadership or system’s crisis? What system undermined Ethiopia as a multinational state;and reduced to pieces Ethiopiawinet as common national identity?

- What is the political economy of Ethiopia that perpetuates elite capture, corruption, poverty, unemployment, hyperinflation, and poor administrative services?

- Why is Ethiopia still unable to match its expertise, disciplines and other human capital poolwith tasks and responsibilities and institutionalize its modernization process regardless of geographical location or ethnicity?

- Is there a national consensus on Ethiopia as a single geopolitical entity or is it a mythologythat the Ethiopian people as a whole must face?

- What institutional and systemic policy matters triggered the war in Tigray? Why did Ethiopia go to war in the first place? What is the end game? Is the widely held perception that the end game is to replace one ethnic dominance by another imaginary?

- Why does the Ethiopian government leadership give contradictory signals to pro-Ethiopia combatants who are shedding their blood in defense of Ethiopia? Is the war over? Does not the government of Ethiopia have a responsibility to explain its gyrating and unpredictablepositions and actions to the Ethiopian people?

- Who is accountable for atrocities of innocent Amhara and Afar civilians and for the incalculable economic destruction? Should the government of Ethiopia, in principle at least, demand that the TPLF and its core supporters overseas pay compensation to victims and compensate for the rebuilding and reconstruction of economic assets? Is forgiveness without redress prudent?

- Does the government of Ethiopia have a post war road map that demonstrates or at least signals that a TPLF-like conflict will not reoccur? Is the Commission empowered to change the Constitution?

- Is the Commission expected to produce a roadmap? If so, is it empowered to make political decisions?

- Is there merit in considering independent and neutral international advisers in the peace-making process?

Ethiopian intellectuals and scholars as a group must entertain if not acknowledge that these and other fundamental questions require research, analysis, and forward-looking recommendations from them.

Ethiopia’s future seems bleak not because of lack of zeal and support from the Ethiopian people. They have demonstrated that they stand for Ethiopia as Ethiopians. Ethiopian combatants fought hard and valiantly. Ordinary citizens sacrificed a great deal by offering material and spiritual support in the fight against terrorism. People feel rightly that the gap that is out there is an insipid and timid politicalleadership that has made Ethiopia a rudderless ship.

The way out for Ethiopian society from a cycle of primarily ethnicity-based political violence is a holisticand systems approachto peace making. Ethiopian intellectuals and scholars together as Ethiopianscan mitigate the glaring gap in political leadership by providing bold and far-reaching intellectual and scholarly fuel to the Commission.

Part III will follow soon

February 4. 2022

“… staggering atrocities and destructions and release TPLF and other terrorists …”

The released “other terrorists” include Eskindir Nega. Right?