Rasmus Sonderriis

No, this is not another stereotypical African war, so let’s stop treating it as one. It is time to support and build with our Western ideals, not to harangue and destroy with our saviour complex

REPORTING THE VIEW FROM ADDIS ABABA

The author Rasmus Sonderriis is a Danish-Chilean journalist who has lived in Addis Ababa for a total of six years since 2004.

Awhite face like mine still draws attentive hospitality in the capital Addis Ababa, but these days it comes with a wariness that can, on occasions, veer into outbursts of anger.

“You Europeans are out to divide and rule us Africans again, huh?” a university student scoffs.

“What do you mean?” I inquire, ever so innocently.

“That those wishing to break up our old, great nation are attacking us brutally, and all you can do is to berate, punish and weaken us!”

“The disagreement with your government is only,” I try to tone it down, “over humanitarian access in Tigray. And perhaps the alliance with Eritrea.”

“Come on!” she shouts and flails her arms around. “What did you do last time your democracies were under threat, last time the enemy marched on your capitals? If I’m not wrong, you used hunger as a weapon against Germany, allied yourself to a monster like Stalin, and dropped nuclear bombs on Japanese civilians. And yet we supported you, because we saw the bigger picture of the fight against fascism.”

“Good on you, but you don’t want Tigrayans to starve, do you?”

“Of course not! We all have Tigrayan friends, even relatives. We wish them well. But we do not suffer do-gooders making everything worse! They’ve made no apology for supplying the terrorists with hundreds of trucks and who knows what else that’s being used to kill us. Now they say we should provide our fascist aggressors with fuel, electricity, transportation, telecoms, internet, even banking services. Are you kidding me?! It’s not your charity workers, it’s us, the sons and daughters of Mother Ethiopia, who must live or die here, defending our liberty!”

I reflect on her points. The fervour springs from deadly urgency, since the civil war that erupted one year ago has spread towards the capital. It is going to demand immense sacrifices, mobilising all human and economic resources. So why does the analogy with WW2 come across as off-the-wall? Because in the Western mind, war in the Horn of Africa does not evoke an epic ideological showdown, but rather misery and pity. This might be why US and EU policy on this conflict, as well as the accompanying media coverage, seem to be shaped by aid officials rather than by political and military analysts.

The same blueprint is applied as in South Sudan, demanding a ceasefire to enable relief supplies and let the diplomats work out some magical power-sharing deal, droning out that “there’s no military solution”, wielding trade restrictions and aid cuts to get the hotheads to think straight. In the absence of Islamists, telling friend from foe is assumed to be pointless, so both sides complain of both-side-ism. Democratic legitimacy is not even an issue. The small matter of who is fighting for what kind of Ethiopia is boiled down to something tribal.

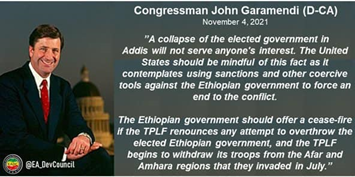

If the aim has been to lessen the suffering, it has been utterly counterproductive. When Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed declared a ceasefire and withdrew from Tigray on 28 June, the regional government dismissed it as “a sick joke” and went on a grand offensive. Since then, its leader, Getachew Reda, has been tweeting bravado about new conquests further and further away from Tigray, boasting how his artillery is trained on cities full of refugees. He presents himself to the world as a plucky rebel in the bush, but, as recently as 2012–2016, his job was to justify the imprisonment and torture of the opposition as the hard-line Minister of Information in the capital city, which he is now threatening to retake by force. The US urges him not to try that, but, at the same time, tells the national air force to stay grounded and has just imposed sanctions that will eliminate jobs for poor Ethiopians. Even Facebook has piled on. After years of criticism for ignoring small ethnic militias stoking deadly hatred on its platform, the social media giant deleted the national leader’s stirring call to block the advance of the invaders for ‘inciting violence’. It is a good thing that Facebook was not around to censure Winston Churchill for inciting violence on the beaches.

“It’s obvious what the West is playing at,” says the student and nearly everyone else in Addis Ababa these days. “Regime change!”

Well-founded or not, Ethiopians have become convinced that the US and EU are no longer allies of their new, still-vulnerable democracy, but are determined to violently restore the dictatorial ancien régime of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front, TPLF.

First there was ‘Abiymania’

The TPLF’s dominance of Ethiopia, lasting from 1991 to 2018, has been characterised as state-led development, China-style, and as crony capitalism, Russia-style. Tigrayans make up only 6% of the population, and the TPLF ruled in a coalition with other ethnically-based parties, called the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, EPRDF, led by the Tigrayan strongman Meles Zenawi. His death in 2012 was followed by popular protests and regime crackdowns in a vicious cycle that was finally broken in March 2018, when the TPLF was isolated within the EPRDF, from whose ranks rose the incumbent Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. He is an Oromo, the most populous ethnic group making up about 35% of Ethiopians, although, in line with centuries of common practice in this country, he has mixed ancestry and a mixed marriage.

On December 1, 2019, the EPRDF became ‘the Prosperity Party’, uniting all the ethnicities. The TPLF was invited to join, yet preferred to retreat to its stronghold, the northern region (or ‘state’) of Tigray, where it continued to rule in its old, authoritarian ways, ignoring federal courts and enforcing its own interpretation of the constitution.

The ruling-party name change — do notice how ‘revolutionary front’ turned into ‘prosperity’ — signalled replacing militarism with economic liberalization and opening up to foreign investors. If this was not enough music to Western ears, there was also asking forgiveness for past oppression, mass release of political prisoners, prosecution of former corrupt and cruel officials (although some found protection in Tigray), unprecedented press freedom, inviting exiled politicians back home for dialogue, appointing women, not just to the ceremonial presidency, but also to the most powerful positions in the cabinet, a famous human rights presiding the Supreme Court, a previously imprisoned opposition leader serving as chairwoman of the National Election Board, and a territorial concession to make peace with neighbouring Eritrea, which is under despotic one-man rule, but is historically and culturally a close sister nation.

This string of West-pleasing measures earned Abiy Ahmed the Nobel Peace Prize on December 10, 2019. It was no secret back then that his lighter touch had allowed ethnic chauvinism to rear its ugly head. Tigray was uncooperative but orderly, looking like the least of his problems. Deadly ethnic cleansing in other parts of the country had displaced nearly three million people and given rise to dark mutterings about “another Yugoslavia”. These tough challenges were just an additional reason to give Abiy Ahmed some morale-boosting recognition. Those were the days of peak ‘Abiymania’ in the West. It was also the high point of Ethiopians’ trust in the rich and powerful democracies.

Attack from the North

“Why the West wants to sow chaos? To punish us for trading with China,” the student suggests. “Or to sell us out in a bid to please Egypt in some deal between the USA and Israel.”

“Come on!” Now it’s my turn to shout and flail my arms around. “We Westerners need Ethiopian stability, an ally and trading partner, not 115 million refugees. There is no way supporting the hated TPLF can be in their, I mean, in our interest! Impossible!”

“That’s what we used to think,” says one local after another in my lively chats, in English and in my broken Amharic, all over Addis Ababa. This time it is the manager of a dry cleaner. He goes about it diplomatically by thanking Ronald Reagan for helping to defeat communism. “But here we are, the West has stabbed us in the back and left us bleeding. At first, we were surprised. Now we’re furious! That’s why people come up with these crazy conspiracy theories.”

There is little on the national news about the fierce fighting going on, as we talk, about four hundred kilometres to the north. Some citizens take issue with this official silence. “Our towns are being burnt, our people are getting massacred, and the television shows our leader inaugurating an avocado farm. When criticized, he just says our troops will eat avocados too. That doesn’t really lift morale.” Others suggest that belligerent jingoism would merely aggravate ethnic tensions and alienate the West even further. Many have their own source of information, namely friends and relatives who have fled southwards.

“What we don’t trust is the Western fake news,” says a mechanic. “So-called Africa reporters sit in fancy hotels in Nairobi or Cape Town and sex up their prejudices with incendiary accusations of tribal hatred. They ought to take a sober look at our political landscape. In every Ethiopian ethnicity there are indeed dangerous fanatics lurking in the wings, peddling age-old grievances and thirsting for revenge. The one thing they have in common is that they hate the prime minister. The rest of us may criticize him, look at this!” He shows me an unflattering caricature of the national leader in a magazine. “But we know that if he loses, we’re doomed. By the way, Doctor Abiy loves the culture and people of Tigray. He speaks fluent Tigrinya, now who’s reported that?”

Indeed, some media outlets have spewed a toxic blend of ignorance and self-righteousness. The UK Daily Telegraph mistranslated Abiy Ahmed’s ambition of achieving food self-sufficiency into a vow to ban food aid.

CNN chose early on to take the side of the TPLF, and has gone about it with partisan zeal, as if Abiy Ahmed were the new Donald Trump. On November 5th, it escalated to what is being perceived in Ethiopia as outright psychological warfare, with stories creating the impression that the government was collapsing, including the spine-chilling headline “Tigrayan troops just outside Addis Ababa”. This was false and easily disproven.

The casus belli has been blithely misrepresented as the holding of unauthorized elections in Tigray. Even long-reads use zero column space on how the TPLF struck the first murderous blow. As the student puts it: “It’s like chronicling US involvement in WW2 without mentioning Pearl Harbor.”

Date of infamy

The date that will live in Ethiopian infamy is November 4, 2020. A coordinated assault was launched at night on five federal military bases in Tigray, resulting in desperate combat and fatalities at least in the hundreds. The TPLF has justified it as a “pre-emptive strike”. Reports of soldiers gunning down their own comrades-in-arms shocked the Ethiopian public, as did, five days later, the massacre of an estimated 700–1200 non-Tigrayans in Mai-Kadra.

It is important to understand that, following the border war with Eritrea in 1998–2000 and two decades of subsequent tension, most of Ethiopia’s military hardware was located in Tigray. Moreover, much of the army’s expertise was concentrated among Tigrayans during 27 years of TPLF dominance. Having made peace with Eritrea, Abiy Ahmed had a good case for relocating national armouries southwards. The TPLF struck before he got the chance.

In the first of two concise and crucial working papers (highly recommended to journalists and policy-makers who are open to different perspectives), Jon Abbink, a veteran Dutch expert on Ethiopian affairs, argues that, hypothetically, if Abiy Ahmed had not responded to the TPLF attack, it would have torn Ethiopia asunder by emboldening ethnonationalist extremists across the country. Rejecting the stereotype of the African war does not mean romanticising Ethiopia’s authoritarian political culture, in which weakness at the centre invites armed challenges from the provinces. It should also be noted that a year earlier, Sebhat Nega, co-founder and leading ideologue of the TPLF, declared civil war to be inevitable. In other words, the TPLF had long been preparing for it.

In Addis Ababa, although nearly everyone desired the defeat of the TPLF, given the military realities, public opinion varied as to the wisdom of striking back after the attacks on the bases. It caused revulsion and sapped morale when federal forces, and especially their allied Eritrean troops, were reported to have committed shocking war crimes, for instance, in the holy city of Axum. At least this was admitted by the government-appointed Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC). The courts have indicted 53 Ethiopian soldiers, and so far convicted four. This process must carry on, even though no cooperation on human rights can be expected from the TPLF. The latest report , drawn up in full cooperation between the EHRC and the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, finds war crimes have been committed by both sides, but does, after all, reject the accusation of genocide and using hunger as a weapon.

Racism at play?

Racism has been mentioned as a factor in the West’s treatment of Ethiopia, most harshly by Jeff Pearce, a white Canadian, who has built a large following among English-speaking Ethiopians for his independent journalism and passionate solidarity. Accusations of racism have become so clichéd in 2021, that a kneejerk response is the rolling of eyes. However, in this case, they are indeed well-founded.

As for the policy-makers, it starts from the stereotype of the African war as just a clash of big men’s egos. This did fit the Eritrean-Ethiopian war, but is not applicable this time. It continues with ‘the white saviour complex’, which frames our role as humanitarian, impartial condemnation of Africans senselessly killing one another. The white tribes in the Bosnia War also committed atrocities on each other, but, in that case, we did stand in solidarity with the side that best represented our ideals of democratic coexistence. Finally, it is colonial-era mentality when economic strong-arming is expected to bring Ethiopians to heel, when all it does is to wound and antagonize a proud people. It is still unlikely to happen (other than on CNN), but if, Heaven forbid, the TPLF were to reach Addis Ababa, the EU and US will deserve all the blame that they are bound to get for the bloody mayhem.

While Abiy Ahmed’s authority is thus being consistently undermined by Western policy, Western media assume he is in total control. When his government gives permission to aid convoys, after which security checks hamper their advance, the prime minister is seen as the sole culprit, although ordinary Ethiopians’ distrust of the relief agencies has clearly become an obstacle on the ground. The saintly aura of the do-gooders always goes unquestioned, even when two senior UN officials from African countries were dismissed for suggesting pro-TPLF bias among UN high-ups. One detailed psychoanalysis of Abiy Ahmed after another, all the way down to what his mother told him when he was seven, substitute for political and military assessments. Der Spiegel, among others, suggests that he cunningly waited for his Nobel Peace Prize before turning rotten. It makes no sense that he would crave the approbation of the great and good Norwegians on one day, and then not give a toss about the West’s opinion on another. But raving insanity is a better sell than sober context analysis.

This is a shame. There are crucial discussions to be had about how Abiy Ahmed’s government is navigating, often zigzagging, Ethiopian identity politics, trying to co-opt moderate ethnonationalists (for instance, by increasing the number of ethnic states from 9 to 11), while cracking down on forces perceived to be behind the grisly ethnic violence. In a country that is still baby-stepping into democracy, this issue is fraught with dilemmas.

Rather than sorting those out, The Economist puts the problem down to the Ethiopian leader being “increasingly paranoid and erratic”. Curiously, those two words perfectly characterise the Ethiopia coverage of The Economist and like-minded news outlets. Erratic in turning Abiy Ahmed from a Nelson Mandela into an Idi Amin overnight. And paranoid — dangerously paranoid! — in ascribing genocidal intent to his actions.

Trigger word ‘genocide’

Who would want to be called, let alone be, an apologist for genocide? It is the ultimate stain on the conscience of humanity, so on the scale of moral trade-offs and liability risks, it seems safer for Western journalists and do-gooders to make one accusation of genocide too many than one too few.

And yet, placing that word right, left and centre, as the TPLF managed to get done from Day One of the conflict, has many deeply perverse effects. Providing an intimidating insult to hurl at critics is the least severe. It also demonises fellow Ethiopians and prompts cries for revenge, with the justification that “we must kill them before they kill us”. Worst of all, it conjures up a “total war”, as Goebbels once put it, which is precisely the TPLF’s method to subjugate the Tigrayan people to its militarism.

If annihilation looms large, one cannot afford scruples over massacring the other side, recruiting child soldiers, looting aid warehouses, forging an alliance with ethnic cleansers. Noticeably, the media narrative has made no bones about how the TPLF ruled with an iron fist for 27 years. But rather than garnering sympathy for the democratic side, this makes the genocide charge sound more plausible by suggesting a motive.

“Our family has lived in harmony with other ethnicities in this city for forty years,” says a hotel owner in Addis Ababa. “Yes, some people think Tigrayans like us became rich through favours from the TPLF bureaucracy. And yes, I did support the TPLF when they were in power, but they were toppled fair and square, because they’d lost the ability to rule, and they started this war out of spite. We worry more about people in Tigray than about ourselves here in Addis, but there is always the danger that a mob will take it out on us, when the TPLF commits the next outrage. I cannot vouch for all his allies, but Abiy is not hateful. He’s not going to do what they did to the Eritreans.” He is referring to 1998, when all Ethiopian citizens of Eritrean origin were rounded up, had their entire belongings expropriated, and were bussed to Eritrea. “During the seven months when federal forces were in control of Mekele (the capital of Tigray),” he remarks, “power and telecoms were restored, and food aid was even paid for by Abiy.”

What should the West do?

The think tank International Crisis Group, funded by Western governments, illustrates the fundamental policy contradiction in its latest working paper, predicting disaster if the federal authority continues to weaken, yet endorsing the diplomatic snubs and economic sticks that are having precisely this effect.

Ethiopians, bitter from experience, will say my thinking is naïve and has yet to evolve, but I still believe the US when it declares its support for the territorial integrity of the Ethiopian state. Given that the TPLF officially does not care about Ethiopian unity, this ought to make it easy for the US to finally take sides.

And I still believe the EU when it calls for an immediate return to the constitutional order. Surely, the EU has already got the memo that the Constitution of Ethiopia offers no concessions to armed insurrectionists, right? If so, the EU has in fact demanded that the TPLF disarm and submit to the courts of justice. Now, spell it out directly! This is also the safest way to avoid famine in Tigray.

Jon Abbink discusses what is behind this ongoing foreign-policy blunder, such as TPLF supporters working for international institutions (for instance the WHO director general), well-funded lobbying, influential people in the West who were close to and are still in awe of the TPLF dictatorship, and online TPLF activists in rich countries easily tricking lazy, narrative-driven media. Another factor could be that aid organisations in this day and age are unapologetically political, but tend towards virtue-signalling with soft pacifism rather than grappling with hard consequences.

However, it is not too late! As it dawns on Western policy-makers that the TPLF is a real military threat, more nuanced statements and even strong criticism of the policy so far are beginning to come out. Just as in the Luanda Leaks case, the fearless pioneer is Ana Gomes, a Portuguese social democrat and former MEP, who led the EU team of election observers in Ethiopia in 2005, when she denounced the fraud and the ensuing bloody crackdown. She is such a folk hero in Ethiopia that there is talk of naming something important after her. She recently addressed her compatriot, UN Secretary General António Guterres, with a tweet warning him that the TPLF is a “dangerous band of criminal oppressors and liars”. She added a video link on how “history is repeating itself”, comparing the Western betrayal today to when the League of Nations let Mussolini invade Abyssinia in 1935–36.

If this is the script laid out once again, eventually, after a shameful delay, the liberal democracies will get around to being on the right side of history. Both from a humanitarian and from a self-interested viewpoint, it makes perfect sense for the Western powers to get squarely behind Ethiopia’s multi-ethnic democracy. Or at least to stop adding to its distress.