“IOM and UNFPA officials are responsible for the termination of two strong ladies. Both current officials must be fired.” UN Africa staff members

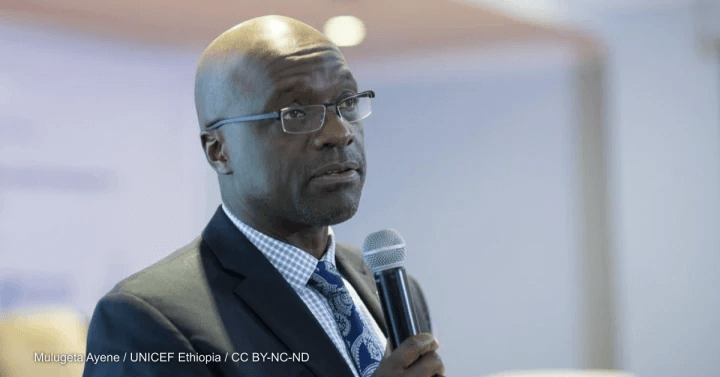

Leaders in the international aid community said famine existed during the war in northern Ethiopia without the necessary food insecurity data to underpin it, according to former World Food Programme country director for Ethiopia Steven Were Omamo.

“Without doubt, there was deep food insecurity in Tigray. But there was no evidence of famine,” he wrote in a recently published book, speculating that famine was used to tap into the “multi-billion-dollar hunger industry” or as a “colonial paternalistic” urge for the global community to “feel good” about itself for averting it.

The polarized conflict in Ethiopia has been marred by scarce information, misinformation, and self-censoring as humanitarian workers faced government backlash, which included organization suspensions and expulsion of senior United Nations officials.

Omamo’s book, “At the Center of the World in Ethiopia,” offers a rare glimpse into the complex interactions between the government, other parties to the conflict, and the aid sector. Aid workersDevex spoke with agreed there were gaps in the data needed to assess whether famine existed. But some disagreed with Omamo as to why the word “famine” was used and said the region was intentionally placed in a situation where data collection was impeded.

Omamo was WFP’s Ethiopia country director when the conflict began in November 2020 and left the position in December 2021. He received internal criticism for being “too close” to the government.

DevExplains: How is a famine declared?

Inside the IPC process to declare a famine.

In his book, Omamo writes of an “overt politicization in the deliberately misrepresented” use of the word famine. In June 2021, Mark Lowcock, who was finishing his role as the U. N. top humanitarian chief, said: “There is famine now in Tigray.” Last year, he said the Ethiopian government blocked a declaration. His successor, Martin Griffiths, said he assumed famine was taking place.

The United States said 900,000 people were on the verge of famine. Omamo said his team concluded that the figure was “fabricated.”

Without “clear evidence” the use of famine was a “sham,” he wrote. But that wasn’t to distract from the fact that “food insecurity was real” and there was “extreme human suffering.”

Was there famine?

Famine declarations are highly political. The process includes reaching three thresholds of data and is typically made jointly by a federal government and U.N. agencies.

In Ethiopia, data collection was limited as violence and lack of access to fuel stymied efforts, he wrote. The government also cut internet, telephone, and banking services in Tigray.

The data available was mainly drawn from remote computer-assisted phone surveys and a limited number of face-to-face surveys with people arriving at receiving centers, he wrote. Western Tigray wasn’t analyzed.

Because of this, the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification, or IPC, findings “needed to be interpreted with great care,” he argued, but the international community was “chomping at the bit” for results. Findings were leaked before the process was finished, and as engagements with the government were still ongoing.

A report was then issued, without government backing nor the necessary caveats, he said. It said over 350,000 people were in catastrophe-level of hunger, or IPC Phase 5, noting it was the highest number in that category since Somalia’s 2011 famine. But the report didn’t declare a famine.

Omamo said “there were major problems with the IPC analysis,” and the casualty of politicizing the report was that it wasn’t used “as the planning and operational support tool” it could have.

“Whether there was ‘near famine’ in Tigray will never be known,” he wrote.

More reading:

► Exclusive: Russia, China foiled UN meetings on Tigray famine, says Lowcock

► WFP regional director says ‘virtually no aid access in Tigray’

► In Ethiopia’s Tigray, only 1% of people needing food aid received it

In response, Lowcock told Devex he stands by his statement that there was famine. The IPC report was clear in its findings, he said, and by not signing off on results, the government in effect blocked them.

Devex spoke with four aid workers who agreed that there were gaps across the three pillars of essential data needed for assessment of potential famines. They all asked to remain anonymous given the sensitivities.

One aid worker said though field visits were conducted, including in less accessible areas, the data was patchy. The figure that over 350,000 people were in catastrophic levels of food insecurity was reached by triangulation of data.

Population-level mortality data was not available — the Ministry of Health no longer had fuel to move, nor a phone connection. Field visits became more difficult as access to fuel grew scarce for humanitarians. “The region was specifically put into a situation whereby collecting this kind of data was impeded,” this aid worker said.

There was widespread destruction of health systems. In other conflicts, a district health office might still have data that health workers can phone in, even in areas without humanitarian access, the aid worker added. But in this conflict, structures were either deliberately destroyed or damaged and most health workers were displaced, without fuel or mobile phone service.

Despite the challenges, aid workers did find alarming cases of acute malnutrition in children under 5, pregnant women, and lactating mothers. This was particularly true in rural areas where “these people couldn’t get out and food wouldn’t come in,” the worker said. There was a better picture of food insecurity and acute malnutrition data at the local level — but not across the entire region.

While Omamo wrote that “there was no evidence at all of anyone dying of hunger,” the aid worker said there were reports of deaths from hunger in several zones, which were followed by visits to villages to gather evidence. Different regions were worse off than others, whereas, in others, there was no evidence of starvation.

What ‘does not fly’ in Ethiopia

During his tenure, Omamo said he faced “widespread” internal criticism that his office wasn’t moving quickly enough nor speaking out against the government. He said his hands were tied without government approval to start food relief operations. What might happen in South Sudan or Haiti “does not fly in Ethiopia where the Government is strong and in the driving seat,” he wrote.

He wrote that WFP needed an “explicit request” from the government. In Ethiopia, relief food distributions are divided among WFP, the government, and the USAID-funded Joint Emergency Operation Program, or JEOP — the latter two were responsible for food relief operations in Tigray, Amhara, and Afar, he told Devex. WFP didn’t receive a request to start food relief operations in Tigray until March 2021 — four months after the war broke out.

Ethiopia suspends MSF and NRC over ‘dangerous’ accusations

The Ethiopian government suspended Médecins Sans Frontières and the Norwegian Refugee Council from working in the country, amid an escalating humanitarian crisis in the country’s northern regions.

He also described a rift between the realities his in-country team faced and expectations of staff at WFP headquarters and said he wasn’t trusted because he had a good relationship with the government.

Previous programming was mainly development-focused where partners, including the U.N., worked under uncommonly controlling government oversight as “the price you paid for working with Ethiopia,” another aid worker involved in the response told Devex. But this relationship must evolve when the government is a party to the conflict, the worker said, with a willingness to challenge the government and raise global pressure to increase access, rather than wait for an invitation.

Early on, humanitarian workers signed an access agreement. Omamo told Devex some thought it “tied the humanitarian community’s hands too much,” giving the government veto power.

“Those objections were very abstract because the situation on the ground was that nothing was happening. We needed a way to jump-start things,” he said.

Donors put pressure on the U.N. to improve access. The global body in response brought in a quasi-parallel team, reporting directly to headquarters, bypassing in-country structures. This “disgruntled” in-country staff, the aid worker said.

Omamo said the conflict was the overarching barrier for his teams — warring parties controlled areas and decided whether to allow in aid.

A ‘Manichean’ narrative?

Omamo told Devex his book isn’t intended to condone warring parties, but he objects to what he calls a dominant narrative that conflict existed solely in Tigray, with the government as the main inhibitor of aid delivery. For example, Omamo said not enough attention was drawn to food insecurity resulting from Tigray forces’ offensive into Amhara and Afar.

One aid worker Devex spoke with agreed and said the conversations were “incredibly Manichean” with a good-guy, bad-guy narrative, leaving “no space for middle ground,” and perspectives like Omamo’s were dismissed as “too close to the government.”

But others are less willing to understate the government’s role in inhibiting aid delivery. Another aid worker told Devex that over the course of the conflict, there were times the government blocked aid completely and times it let some aid in. There were instances aid groups couldn’t use roads not in conflict. When flights were eventually allowed into Mekelle, the government gave “incredible restrictions” on what was allowed in — including denying aid workers of carrying their own chronic illness medication. And cuts to banking, telecommunications, and internet services meant aid groups couldn’t communicate at times with their teams nor pay salaries.

Many times, access problems resulted from Amhara or Afar regional governments and militias, or Eritrean forces, who were Ethiopian government allies, but the government said it didn’t have influence over them in regard to allowing humanitarian access, the worker said.

Aid workers say the operating environment dramatically improved after a peace deal was signed last November. But it’s relative — improvements to a bleak situation, with ongoing access and resource constraints and widespread needs.

There is another claim I have questioning since the start of that stupid but very destructive war. It is the extent of involvement by our Eritrean brothers and sisters. I believed then and I believe now that they had the right to protect themselves and their country. What would any sovereign country would when unprovoked war is declared on them and missiles starting raining above their heads? What would every EU member do in the same predicament? Legitimate self defense should only have a single standard and not double standard. They were reports of rape and extrajudicial killings. Yes these atrocities have happened. But my lingering question has been who did it and to what extent? These evil acts must be thoroughly investigated by more than independent groups set up and specialized in such matters by AU, UN, Doctors Without Borders, EHRC and similar organizations from Asia and Latin America. EU has more than it can handle tracing Wahhabis buyout finances in which they have several officials in Brussels on the hook. Besides EU is too presupposed about the war in the North.

Abiy Ahmed, multi degree murderer disorganized elementary scholl student nver had all degrees he claimed, p behind cheating and lying, he is a honorable liar mutipple degree graduate , all his life cheating.