News of the death of Britain’s longest-reigning monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, elicited a profound response and international grieving. Ethiopians have contributed to the millions of tributes that flooded social media for the late monarch, who died aged 96 on Thursday. The queen’s ties to the country began at least in 1965 when a young Elizabeth accompanied her husband, the Duke of Edinburgh made an eight-day visit to the country. Prince Asfa-Wossen Asserate, a member of the former Ethiopian imperial dynasty, was at the airport as he shared his own recollection in his book, King of Kings: The Triumph and Tragedy of Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia.

News of the death of Britain’s longest-reigning monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, elicited a profound response and international grieving. Ethiopians have contributed to the millions of tributes that flooded social media for the late monarch, who died aged 96 on Thursday. The queen’s ties to the country began at least in 1965 when a young Elizabeth accompanied her husband, the Duke of Edinburgh made an eight-day visit to the country. Prince Asfa-Wossen Asserate, a member of the former Ethiopian imperial dynasty, was at the airport as he shared his own recollection in his book, King of Kings: The Triumph and Tragedy of Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia.

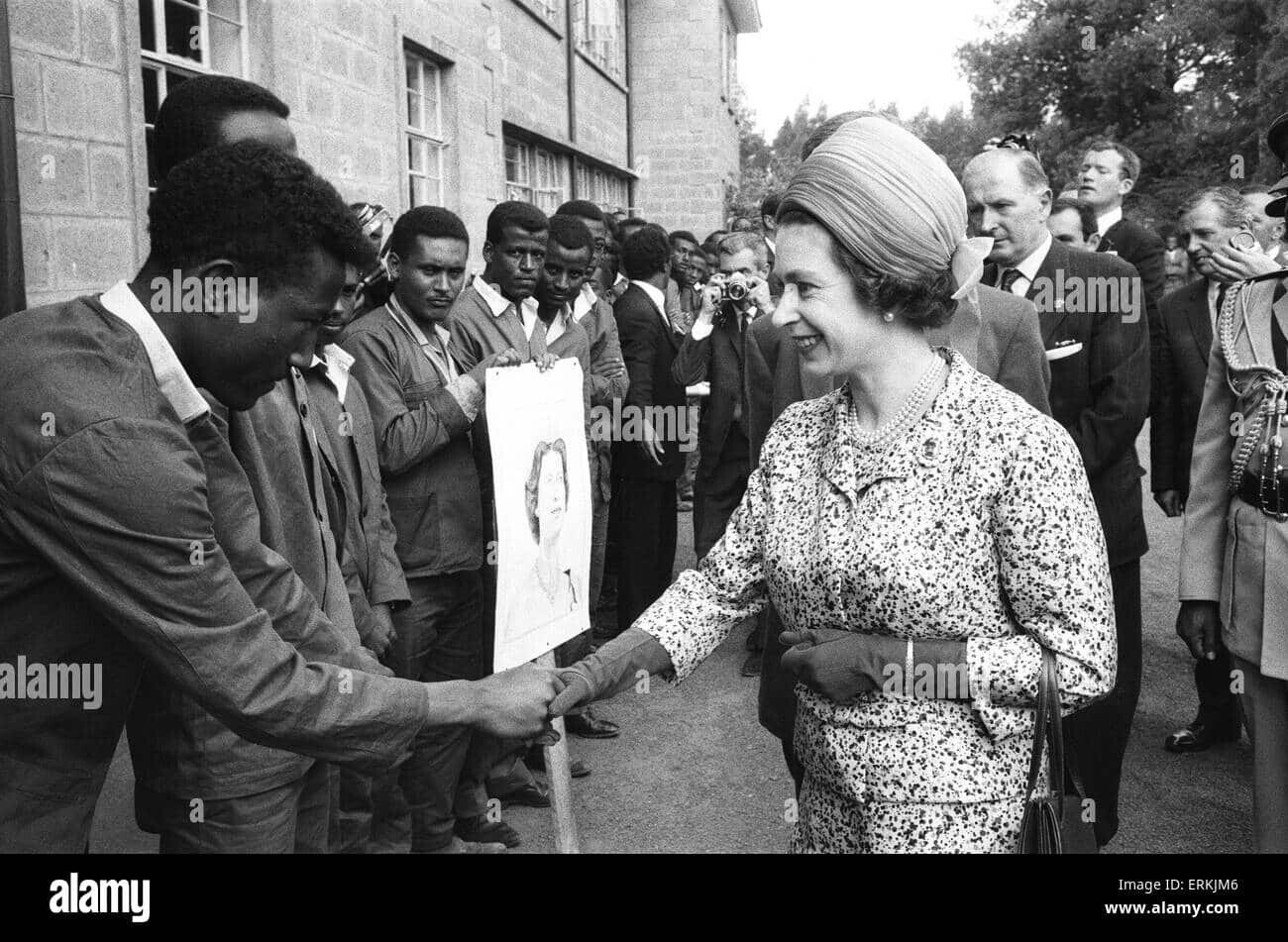

I was allowed to witness two state visits to Ethiopia in the 1960s: those of Queen Elizabeth II and Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi of Persia. Accordingly, the emperor went in person to Addis Ababa airport to greet the queen on her arrival, together with a military honour guard drawn from all branches of the armed forces. For this occasion, Haile Selassie wore the official uniform of an Ethiopian field marshal, which had a very British look about it – all except for his headgear, that is: a two-cornered Ethiopian hat adorned with a golden lion’s mane. His entire cabinet of ministers and all the country’s top generals were present, the former in morning coats and top hats, the latter in full dress uniform.

The golden state carriage that had been built to mark the emperor’s silver jubilee stood in waiting for the two monarchs, and drawn by a team of powerful white Lippizaners and escorted by a brigade of the imperial life guards in red and green uniforms, the coach made its way into the city centre. The route was lined with cheering crowds. The capital’s schoolchildren had been given the day off, and all government agencies and other public bodies were closed. It seemed as though the whole of Addis Ababa had turned out to welcome their distinguished guest. In the evening, a sumptuous banquet was held in the queen’s honour at the Menelik Palace, with over a thousand guests attending. This was to be the last such occasion at the Menelik Palace; subsequently, banquets for state visitors were hosted in the more peaceful setting of the Jubilee Palace.

The golden state carriage that had been built to mark the emperor’s silver jubilee stood in waiting for the two monarchs, and drawn by a team of powerful white Lippizaners and escorted by a brigade of the imperial life guards in red and green uniforms, the coach made its way into the city centre. The route was lined with cheering crowds. The capital’s schoolchildren had been given the day off, and all government agencies and other public bodies were closed. It seemed as though the whole of Addis Ababa had turned out to welcome their distinguished guest. In the evening, a sumptuous banquet was held in the queen’s honour at the Menelik Palace, with over a thousand guests attending. This was to be the last such occasion at the Menelik Palace; subsequently, banquets for state visitors were hosted in the more peaceful setting of the Jubilee Palace.

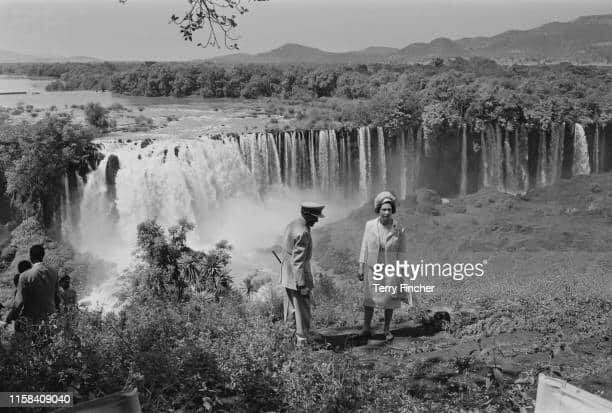

The following day saw the start of the official programme of visits, with the emperor and queen taking a flight down the so-called Historic Route, from the Blue Nile Falls to the rock churches of Lalibela, and then on to see the palaces of Gondar and the giant stelae at the ancient city of Axum. Then their majesties flew to Eritrea, where my father received them with full diplomatic honours at the Yohannes IV airport in Asmara. Limousines with a police motorcycle escort rather than a golden state coach took them into the Eritrean capital. Just days before, the servants at the palace in Asmara had been in a frenzy, with everyone from the butler in his snowwhite tailcoat to the chambermaids making sure that every last speck of dust was removed from the furniture, rugs and carpets. For every state visit, nothing was left to chance. A rigid seating plan was in force at the reception in the throne room.

The following day saw the start of the official programme of visits, with the emperor and queen taking a flight down the so-called Historic Route, from the Blue Nile Falls to the rock churches of Lalibela, and then on to see the palaces of Gondar and the giant stelae at the ancient city of Axum. Then their majesties flew to Eritrea, where my father received them with full diplomatic honours at the Yohannes IV airport in Asmara. Limousines with a police motorcycle escort rather than a golden state coach took them into the Eritrean capital. Just days before, the servants at the palace in Asmara had been in a frenzy, with everyone from the butler in his snowwhite tailcoat to the chambermaids making sure that every last speck of dust was removed from the furniture, rugs and carpets. For every state visit, nothing was left to chance. A rigid seating plan was in force at the reception in the throne room.

The chairs for the Crown Prince and his consort had to be placed at a specified distance from the thrones of their majesties, and set correspondingly lower. The Duke of Edinburgh dutifully performed his allotted role, always walking two steps behind the queen as royal protocol demanded. Prince Philip remained in the background throughout and never committed the gaffe of doing anything.