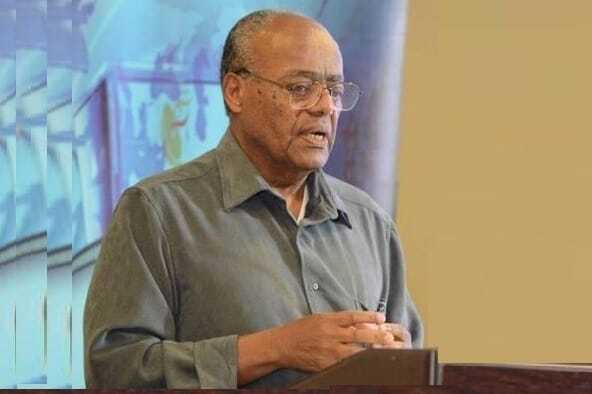

By Worku Aberra

August 2, 2024

Devaluation and Inflation

Introduction

Introduction

On 28 July, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed congratulated the Ethiopian people on his government’s decision to float the Birr. He announced that the value of the Birr would be determined by market forces instead of the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE). This change in economic policy, he claimed, is good news for all Ethiopians. They should celebrate the dawn of a new era of the flexible exchange rate regime, which, he claimed, would bring prosperity to Ethiopia.

However, the histories of many developing countries that have implemented currency devaluation under IMF duress reveal negative economic, political, and social consequences, as seen in Mexico (1994), Argentina (2001-2002), Egypt (2022), and Nigeria (2023), with little long-term economic benefits. What he presented as good news is, in reality, bad news. Instead of celebrating the decision to float the Birr, Ethiopians should be mourning his government’s reckless action.

The Ethiopian government’s adoption of a floating exchange rate regime for the Birr is part of the IMF-World Bank structural adjustment programs (SAP), which have been prescribed to all developing countries. Assigned different names by the IMF and the World Bank, partly because of their unpopularity in the Global Suth, and rebranded as the “Home-Grown Economic Reform Plan” by the NBE, this initiative has mainly resulted in negative consequences in other nations.

SAP is a set of economic policies that the IMF and the World Bank require countries to implement to qualify for short-term loans to address financial problems. SAP incorporates macroeconomic stability, privatization, deregulation, and liberalization. Liberalization involves economic measures that remove government intervention in certain sectors of the economy and promote market forces instead. The adoption of a flexible exchange rate system is part of SAP’s liberalization scheme, where market forces, rather than monetary authorities, determine the value of a currency.

Although a few months ago Abiy Ahmed vowed that he would not sell out Ethiopia’s sovereignty by bowing to external pressure, on 28 July he did exactly that. Subsequent to the government announcement, on 29 July the IMF agreed to extend Ethiopia $3.4 billion over a four-year period to ‘support the Homegrown Economic Reform Agenda (HGER) of the authorities to address macroeconomic imbalances, restore sustainability of external debt and lay the foundations for higher, inclusive, and private sector-led growth’. On 31 July the World Bank extended a loan of $1.5 billion for “ Ethiopia’s First Sustainable and Inclusive Growth Development Policy Operation”. The US embassy in Addis Ababa posted on X that “Market-based FX is a difficult, but necessary step for Ethiopia to address macroeconomic distortions,’’ confirming what some people call the Washington Consensus between the IMF, the World Bank, and the US government on SAP.

Considering that Ethiopia must pay about $5 billion to external borrowers over the next couple of years, according to Fitch, it remains unclear how much of the new loans will be used to repay the debts incurred by the TPLF-controlled government, some of which have been misused, misappropriated, or even embezzled, and how much will be used for development purposes or to alleviate the economic hardship facing the population.

In this article, I will examine the economic impact of devaluing the Birr through the adoption of a floating exchange rate regime. The NBE, echoing the IMF, says that the devaluation of the Birr and the adoption of a market-based exchange rate system are part of a government package that aims to ‘restore macroeconomic stability, boost private sector activity, and ensure sustainable, broad-based, and inclusive growth.’

However, we need to underscore that no macroeconomic reform, however brilliant, will succeed in achieving these goals during the current political instability in Ethiopia. Political stability is the sine qua non of economic prosperity. The floating Birr, with the damage it will inflict on the Ethiopian population, will likely further fuel political instability and lead to negative economic outcomes.

In Part I of this article, I will discuss the impact of the devaluation of the Birr on Ethiopia’s rate of inflation.

Devaluation and inflation

Devaluation and inflation

The NBE argues that ‘The prevailing foreign exchange rate system, though initially meant to help ensure a stable exchange rate and low inflation, has instead resulted in the emergence of an unanchored parallel market exchange rate together with high inflation [emphasis added]’. These claims need to be challenged. The “unanchored parallel market exchange rate” is not determined by the type of exchange rate regime a country follows; it depends on the extent of the underground economy that uses foreign currency. As long as illegal economic activities relying on foreign currency persist—whether due to the authorities’ inability to control them, complicity, or participation—an illegal market for foreign currency will always exist in Ethiopia.

As I will demonstrate in my next installment, the gap between the official and parallel exchange rates has more than doubled since Abiy Ahmed came to power, indicating a substantial increase in the underground economy that relies on the US dollar under his administration. This significant increase suggests his government’s inability, complicity, or participation in illicit economic activities.

Given the high level of corruption in the country, as frequently admitted by Abiy Ahmed, the introduction of the floating exchange rate system will not eliminate the black market for US dollars. Indeed, the combination of pervasive corruption and reform, which grants lax control to banks and allows the entry of non-bank actors into the foreign currency market, will likely cause the black market for US dollars to thrive.

While a fixed exchange rate regime contributes to imported inflation, attributing the current high rate of inflation in Ethiopia to the fixed value of the Birr is incorrect. The primary cause of inflation in Ethiopia today is not the fixed value of the Birr but rather the government budget deficit incurred during the war in Tigray, financed by printing money. Although the increase in the price of imported food, fuel, and other essential goods has contributed to the high rate of inflation rate in Ethiopia, the main cause of inflation is the increase in the money supply.

The NBE argues that floating the exchange rate will contribute to long-term macroeconomic stability, including price stability. However, there is no guarantee it will, as the rate of inflation is influenced by other domestic economic variables, particularly the growth rate in the money supply. According to official statistics, headline inflation is around 33%. The NBE claims that devaluing the Birr will absorb the effect of inflation from the rest of the world. As global inflation rates increase, the exchange rate will decrease, thereby protecting the domestic economy from imported inflation.

However, this argument has a significant number of flaws. Even if we accept the theoretical explanation, the timing is off. Inflation in the rest of the world, particularly in developed countries, has been decreasing. Therefore, the motivating factor for floating the Birr is not external inflation; it is external pressure. Second, as previously stated there are a few internal economic factors that cause inflation; external shocks are not the only factors that cause inflation.

More importantly, the devaluation will worsen the rate of inflation by increasing the price of imported consumer and intermediate goods, as the NBE acknowledges. According to Insider Ethiopia, the prices of imported goods such as cooking oil, pasta, and dried milk have increased significantly in just one day, on 30 July. For example, the price of a five-liter imported oil brand, Hayat, increased by Birr 400 in a single day. As a result of the rising prices of imported consumer goods, merchants are likely to increase the prices of domestic goods and services, thereby raising the overall level of inflation in the country.

There is also the indirect effect of devaluation on inflation. Ethiopia’s manufacturing and service sectors are highly import-dependent. The input-output analysis of Ethiopia’s economy shows that the manufacturing sector is about 40% import-dependent. This means as the price of imported inputs increases, the price of manufactured goods produced in Ethiopia also rises. For example, in the textile industry, Ethiopia imports cotton, textiles, machinery, dye, and other inputs to make garments. Therefore, when the price of these imported inputs increases, the price of garments manufactured in Ethiopia increases as well.

The service sector, especially transportation, is almost entirely import-dependent due to its reliance on imported vehicles, fuel, and spare parts. Similarly, the healthcare sector, with its imports of medicines, instruments, tools, and equipment, is also highly import-dependent. Even agriculture, with its use of imported fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, and seeds, relies significantly on imports. Consequently, the overall price level in Ethiopia is likely to increase due to the devaluation of the Birr, affecting the various sectors of the economy.

The government has indicated that it would subsidize essential products ‘such as fuel, fertilizers, medicine, and edible oil’. However, these are only a small selection of products whose prices will increase. Moreover, the degree and duration of the subsidy have not been specified. Given the government’s concern about its budget deficit the pressure it faces the IMF and the World Bank to reduce its budget deficit, it is unlikely that the subsidy will be substantial or long-lasting.

In this instalment, I have demonstrated how the devaluation of the Birr under the floating exchange rate contributes to inflation. In the next installment, I will examine the impact of this policy change on Ethiopia’s balance of payments and its effect on the black market for US dollars in Ethiopia.

Worku Aberra is a professor of economics at Dawson College, Montreal, Canada.