By Daniel Hailu

I am very grateful to Dawd S. Siraj for taking the time to write a review of my article “The irrelevance of containment as an Ethiopian covid-19 response”. He acknowledged a number of constructive criticisms on Ethiopia’s containment response I offered but did not seem to get my core argument, which related to the response’s (ir)relevance to the Ethiopian context.

Eight months into the pandemic’s history, a consensus is now developing that COVID-19 does not behave similarly in all contexts and that all contexts are not affected by it in similar ways. Hence, the need for context specific response to the virus as a Foreign Affairs article entitled “All Epidemiology is Local” stressed. Based on review of global experience, that article cautions that a one-size-fits-all solution could be devastating to particularly developing countries as it involves detrimental social, economic and political costs, as we witness unfolding in Ethiopia.

To keep the conversation on this all-important subject going, I reiterate some and offer additional reflections and observations on a few aspects of Ethiopia’s COVID response that render it irrelevant to the Ethiopian context.

Is our COVID-19 data locally relevant?

One aspect of relevance of a COVID response relates to a context specific diagnosis of the virus’ situation: (1) how the virus behaves in a specific social, cultural and environmental context, and (2) how that context responds to the virus.

In doing so, generating local COVID-19 clinical data plays an indispensable role. However, as Dawd agreed, critical assumptions that informed Ethiopia’s modeling of COVID-19’s symptomatology, rate of transmission, mortality, and morbidity are imported, logically rendering its related response irrelevant to the national context.

It was understandable for MoH to base its early predications on international experiences and norms since we did not have any prior experience of how the virus would impact us. My contention has been with MoH’s continued reliance on imported data after over 20 weeks since the first confirmed case.

If the MoH focused on building local data in the course of those weeks, as Dawd acknowledged, it would have informed a locally relevant COVID-19 public health response. What is still concerning is, according to sources, management of Case Record Forms in at least at the MCCC has not changed much. This means MoH has no choice but to continue basing the fundamentals of its modeling on imported assumptions?

The Ministry of Finance and Economic Development is in a similar predicament because it had to base its modeling of Ethiopia’s economic outlook under various scenarios based on the same imported clinical assumptions. Logically, the models informed by imported (and, hence, locally irrelevant) data appear to subsequently end up informing public health and economic strategies that could by extension be locally irrelevant.

Is containment still timely for Ethiopia?

Dawd argued that containment is still relevant even in times of community transmission. I agree Isolating confirmed case during community transmission does contribute to slowing transmission by a few days, weeks or months depending on how wide the gap is between the rate of increase in testing and the virus’ rate of transmission in a specific context.

In contexts like South Korea where testing kept a reasonable pace with transmission of the virus, a reasonable size of new infections could be identified and isolated. Otherwise, only a small fraction out of total infections would be confirmed and isolated while the majority continue to spread the virus in communities, making the gain of slowing the transmission insignificant compared to huge cost involved in containment—testing, isolating, and tracing contacts.

Estimates based on different base figures could easily show a significant disparity between the rate of increase in testing and community transmission in the Ethiopian context. Dawd observed that currently infections doubled every 12 days and that every single infected case had a six percent chance of infecting a person daily. Testing has, however, increased at an incomparably slower rate.

Positivity rates are not accurate indicators of the size of infections. However, they can be used to make an indicative estimate of total infections. Accordingly, the daily positivity rate in Ethiopia over the past several weeks irrespective of the number of tests conducted has been between five to seven percent with an outlying rate of a little over four and eight percent. Surely, Addis Ababa has the highest positivity rate but for this estimate we use the lowest positivity rate of four percent.

If we extrapolate that rate to a population of Addis Ababa (assuming it is currently 5 million), we would have about 125,000 new confirmed infections every day in Addis Ababa if we administered a comparable number of tests. However, Ethiopia started testing from a low base and reached to only an average of 18,000 tests during the recent COVID-19 test campaign. Even if Ethiopia’s recently ramped up testing capacity were to be entirely allocated to Addis Ababa, it would be nowhere near that required number of tests.

Hence, it is evident that containment in the Ethiopian context is targeted at only a small fraction of potential infections although it is consuming a huge resource of this poor country. In short, it is too little, too late.

Is the response attuned to the Ethiopian context?

Dawd claimed that every single measure under Ethiopia’s COVID-19 response must have a lot of impact on community transmission and thus trajectory of the pandemic. He based his claim on an apparent comparison of the currently low COVID-19 rates with estimates of the earlier models that predicted catastrophic impact even under the best-case scenarios.

I find this observation suffering from false attribution. What if the Eurocentric assumptions of the models have significantly inflated the potential adverse impact of the virus? What if the particular ways the virus may have behaved in Ethiopia and the resilience that the Ethiopian context may have presented to it had combined to thwart the infectiousness and fatality of the virus, as I suspected in an earlier article

Dawd also noted the difficulty in measuring the impacts of public health interventions. I agree with his observation to an extent, but I also believe we can think of several direct and proxy indicators to systematically evaluate the impacts of a COVID-19 public health strategy. One can, for example, evaluate if national COVID-19 public education has enhanced knowledge of the virus’ mode of transmission and WHO recommended methods of prevention and management of infections.

Without making use of such evaluative studies, we would continue to be spending this poor country’s merger resources without accountability or learning. Limited volume of such research or commitment to adjusting the strategy with findings of such research appear to have actually contributed to the apparent disconnect between Ethiopia’s COVID-19 response and the reality on the ground.

Is containment relevant to our institutional capacity?

Effective implementation of containment requires critical institutional capacities for widespread testing and generating result as quickly as possible, human resource and logistical (and technological) capacity to trace contacts and investment to sustainably manage isolation of infected cases. To the extent any of these in the package is missing or weak, investment on the rest will have a corresponding sub-optimal effective. In countries like China and South Korea where these requisites could reasonably be met, containment can be regarded relevant.

Ethiopia has often copied development policies and interventions that look very good on paper but are too complex or inappropriate, hence, irrelevant for local capacity to implement. Its COVID containment response is a typical example. Dawd’s expressed frustration with Ethiopia’s inability to meet his and colleagues’ recommendation to deploy at least 1,600 contact tracers in Addis Ababa and around 40,000 in the country.

I thought that and similarly demanding recommendations were inappropriate/irrelevant and, hence, unattainable, given Ethiopia’s highly constrained fiscal space. This suggests to the need for policy options that are relevant to and can be implementable with available local capacity or a capacity that can be effectively built in a very short term if really necessary.

Is our investment in COVID-19 response efficient?

In the absence of local clinical data, COVID-19 public health and economic policy making has been driven by fear that exponential growth in infections, morbidity and mortality in Ethiopia might only be ‘a long wait’, as many health professionals who participated in a virtual conference on “COVID-9 in Ethiopia: A big Escape or a Long Wait” held on 7 May agreed. After close to six months since the first confirmed case, Ethiopia’s COVID-19 public health and economic response is still in the waiting mode.

However, even available data shows that the virus is not behaving in the same way here as it did in other hard-hit countries. After a lapse of over 26 weeks, the virus has shown no sign of exponential growth: The more Ethiopia tested, confirmed cases continued to plateau only at a little higher rate in response to increased testing. No matter how many Ethiopia tested, the positivity rate has remained under nine percent. There is a high probability that a significant percentage of those tested negative through the diagnostic PCR test could test positive if they were to be subjected to a concurrent anti-body test because given the slow rollout and per capita diagnostic test, many may have been infected at some point but had already self-resolved (recovered) before they took the PCR test.

Only about one percent of active cases are currently severe, which is diminishing further with increase in testing. The daily number of severe cases shows a negligible increase because the overwhelming majority of severe cases need only oxygen support for a very short time before their status improves to moderate or mild. Confirmed Ethiopia COVID-19 deaths are 1.6 percent of confirmed cases. But given Ethiopia’s very low per capita testing, the real rate is likely to be significantly lower. Twenty eight is the highest daily confirmed death including the controversial inclusion of post-mortem confirmations, which, until MoH stopped disaggregating updates of daily deaths was and, sources say, still is about 50 percent.

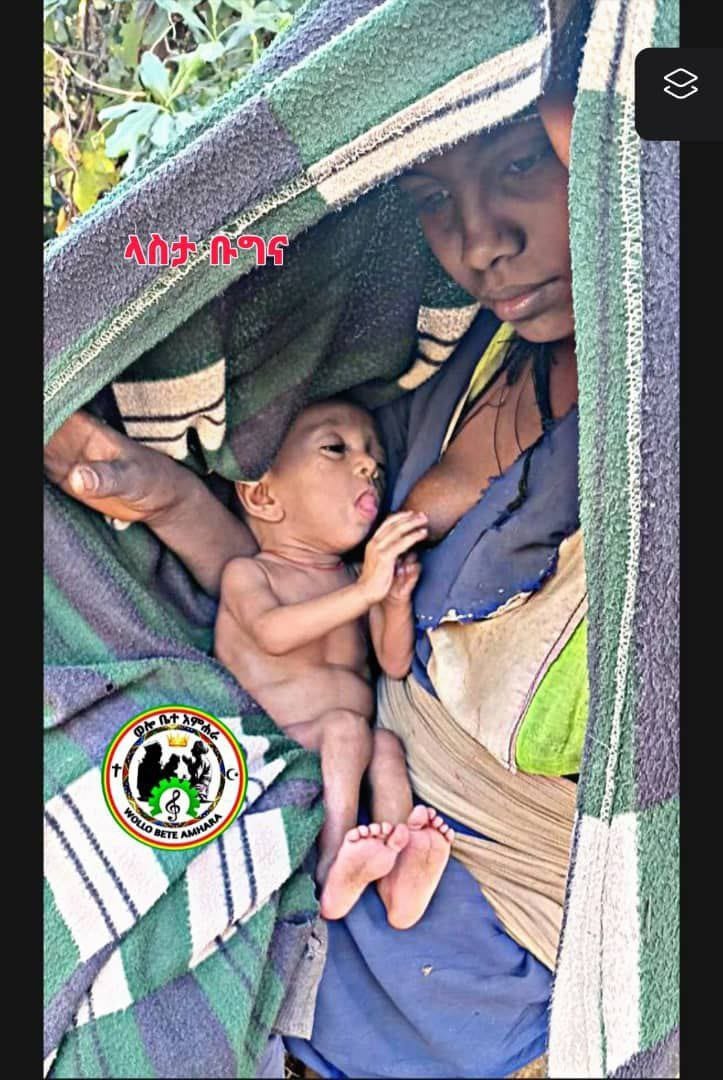

Despite this sluggish COVID-19 trend, Ethiopia’s fear-oriented COVID-19 response has continued to adversely impact the country’s fragile political economy.

A working paper entitled “Economywide Impact of the COVID-19 in Ethiopia published last month by the Ethiopian Economic Association found the COVID-19 public health strategy was crowding out investment on much needed social services and productive sectors of the economy, has significantly reduced labor supply and consumption, among many others adverse impact.

According to the same report, these measures collaborated with slowing of the international supply chain to result in a significant adverse “growth and welfare effects even under an optimistic scenario”. Ethiopia’s COVID response has also prevented scheduled general election which has caused and is still causing much political turmoil and instability.

Isn’t it then high time to question for how many more weeks and months we should continue to sacrifice our fragile political economy at the altar of a strategy that appears to be fighting a fire that has been raging mainly elsewhere? When is the time for putting together a strategy that responds to only the magnitude of the challenge COVID-19 presents in Ethiopia?

Does education on COVID-19 match the situation?

A friend was recently telling me about her observations in a study that was assessing the knowledge, attitudes and behaviors of urban residents including street and slum dwellers. She found that almost everyone she interviewed articulated basic information about COVID-19 they learned from mass and other media: the virus’s mode of transmission, methods of preventions and potential impact upon infections.

She was, however, surprised to find that despite that knowledge most expressed unwillingness in following recommended preventive measures. Explaining their reason, they reportedly told her that COVID-19 was a political hoax created by the Ethiopia government to remain in power or that it was a problem of the ferenji (foreigners). She said, even those who accept that the virus existed thought God would protect them and that they couldn’t do anything about it if it were God’s will.

After I recovered from the virus, I have been trying not to miss a chance to engage with residents who I found violating the government’s COVID safety guidelines, a report on which could make a long volume. For example, soon after my recovery, I found two salesladies in a shop without a mask. I asked them why they were not putting one. They told me that COVID were in ferenji hager (the country of the foreigners) and not here and, hence, they did not need to bother. I tried to explain that it was widespread here in Addis and that without it they were putting themselves and their customers at risk. They told me they knew all the safety measures but were not convinced the virus was pervasive in Ethiopia.

Finally, in case it helped them realize it was, I told them I was infected and just got discharged from the MCC after recovery. At first, they thought I was joking but when I insisted, they became panicky and kept a further pace away from me. A few minutes passed in silence as they collected their breath and then they started hurling questions at me: what I really felt initially, how sick I was, what happened at the MCCC, how many in the isolation center were very sick, whether the government was hiding the number of deaths etc. I learned that I was the first person they had known personally who had the virus.

Officials have lauded the increase in the use of mask as can be observed at main streets of Addis. However, cursory observation at the backstreets of Addis would show that the resident’s business as usual behavior. Many residents told me that they used masks while on the mainstreams to prevent police scrutiny. In recent weeks, in particular, locations such as bars and, more recently, nightclubs are packed with no mask or ventilations.

What caused the public’s defiance and the emergence of conspiracy theories is a subject for a systematic research in its own right. However, based on my conversations with many, it seems, in ignoring the government’s guidelines, many of my friend’s respondents and residents I talked to were being rational: In the early days when they knew nothing about the virus, the public had more or less adhered to the guidelines.

Overtime, however, as weeks and months go by, they saw no sing of the government’s predication materializing. Many said, they did not know a confirmed infection, let alone a confirmed death, within their own social network. Hence, it appeared irrational for them to incur additional direct and opportunity, social and economic costs involved in adhering to the guidelines. So, they gradually moved on with their regular life.

Therefore, if mass education on COVID-19 is to be effective, it should win the trust of the people. To do so, it should acknowledge and build on the public’s lived experience rather than inadvertently patronizing them as disobedient, ignorant, or victims of false propaganda. I believe it is only when the people see the government’s messages matching their actually lived experience that they may give ear to prevention measures that are suited to their social and economic context.

In conclusion, I understand if, in adhering to global norms and overlooking the reality on the ground, the Ethiopian government may be motivated by fear or external and internal political and economic pressures or incentives. However, I believe, redeeming the country from a crippling public health strategy requires a science and bold leadership grounded in the Ethiopian reality.