By

Legislation in June recognizing the Ethiopian Islamic Affairs Supreme Council was a historic progressive move by the State for the Muslim community.

On 11 June, the House of People’s Representatives (the House) approved a bill to legally establish the Ethiopian Islamic Affairs Supreme Council (EIASC, aka the majlis), a move with overarching positive implications for Ethiopian Muslim society

Up until this day, a single religious society has maintained unrivalled legal status before the Ethiopian State.

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church’s continued special legal personality originates from articles 389 and 407 of the 1960 Civil Code. It marks a direct recognition of the church as a legal entity that can form organizations affiliated to it, and it was not subject to annual renewal.

Following the latest parliamentary approval, this number has now risen to three, adding the Ethiopian Gospel believers. The House granted legal status to the Ethiopian Evangelical Churches Council,

Finally, Ethiopia has officially recognized and integrated its religious elements. Post-1991 Ethiopia now becomes a multi-religious State, as it has been a multinational one.

Societal equality

The imperial era mantra that went “ሀገር የጋራ ነው፣ ሃይማኖት የግል ነው”, which means “country belongs to all; religion is personal”, has been a living memory, a counterfactual, until now. Because of this, the House’s glad tiding is the real deal that the old and the new generations are equally upbeat about.

Yet the move has less to do with the troubled majlis and more to do with the mass of Ethiopian Muslims. The majlis institution has for long been seen as anything but a sui generis spiritually Muslim in the eyes of the Ethiopian Muslims, and it is something they hardly identify themselves with.

The malfeasance of the majlis, rooted in lacking any shared vision and its institutional ineptitude, is one thing. But it is quite another, and a most damning one, when it stands against Muslims’ shared identity and becomes instrumental to the State’s repressive policies against the community.

It did this by giving overt support to measures the Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) government took.

In fact, many Muslims likened the majlis to one of the State’s ministries mandated to target Muslims. The majlis behaved and acted as part of the State security apparatus. The last three decades of its institutional history in particular manifest this. And that is why many Ethiopian Muslims resisted impressively and peacefully in late 2011.

The State’s act in the House is, thus, way beyond the mere commendable de jure precedence to authoritatively consent to the legal establishment of the Ethiopian Islamic Affairs Supreme Council (EIASC). Instead, for the wider Ethiopian Muslim community, this is a fundamental issue tied to the antique existence, underlying identity, unfettered equality, and fair justice as a religious community vis-à-vis the Ethiopian State.

Equality milestones

Two milestones are relevant to the Ethiopian Muslims’ question.

The first episode connects us with the 20th Century revolution marked by the demise of the empire that closed one key chapter about the question of State-Religion relations in Ethiopia. The other highlights the opening of a new chapter in the question of State-Religion relations and religious equality

In the mid-1970s, while the revolution was gathering pace, Ethiopian Muslims flooded the capital demanding the separation of State and Religion. The pre-revolution State-Religion relations served mutual political and economic interests.

One of the key instances powerful enough to capture such marriage could be that, the Church symbolized the Christianity of the State through the established official status the 1955 constitution provided under article 126. In exchange, the name of the Emperor should be mentioned in all religious services. Such an enduring bond that glued the two actors ultimately faced the wave of popular anger demanding change, including Ethiopian Muslims.

As historians noted, it was their chant “ሀገር የጋራ ነው፣ ሃይማኖት የግል ነው” and the demand for equal status for their religion that reverberated. Shocked by the biggest demonstration which brought about onto the streets over 100,000 people, members of the aristocracy reacted strongly. The reaction was interpreted as a critical challenge that continued to undermine the historical position of the State.

The legitimate rights that Ethiopian Muslims demanded were critical to once again delegitimize the exclusivist discourse that had been reigning for centuries. Characterizing the discourse as unrepresentative to the wider Ethiopian polity, Muslims called for its disempowerment and for setting the State free so that it remains neutral and able to provide equal status to them.

The Muslims served as a key positive force that contributed to the 1974 revolution. Subsequently, the Ethiopian State dethroned the monarchic regime and turned a new chapter that parted ways with religion under the socialist military junta, the Derg.

As for the question of equal status, of becoming a directly recognized organized religious society and a judicial body that Ethiopian Muslims were equally struggling for, they had to wait until late 2011 when a critical juncture recurred in their history of oppression.

The Muslims’ renewed, but again seriously organized, demand for equal status resurfaced in December 2011, a part of the landmark peaceful struggle known as Dimtsachin Yisema. It all began when Ethiopian Muslims uncovered an Ethiopian government plot that targeted their autonomy and identity.

Historic repression

The EPRDF government was about to undertake an attack against Ethiopian Muslims in collaboration with the majlis. The government sponsored and invited a little known, ‘moderate’, sect headquartered in Lebanon, al Ahbash. This sought to alter the foundational beliefs and practices of Ethiopian Muslims that the State labelled as an existential threat. Foiling this ill-fated State-led operation, Muslims converged around a common cause, regardless of their differences.

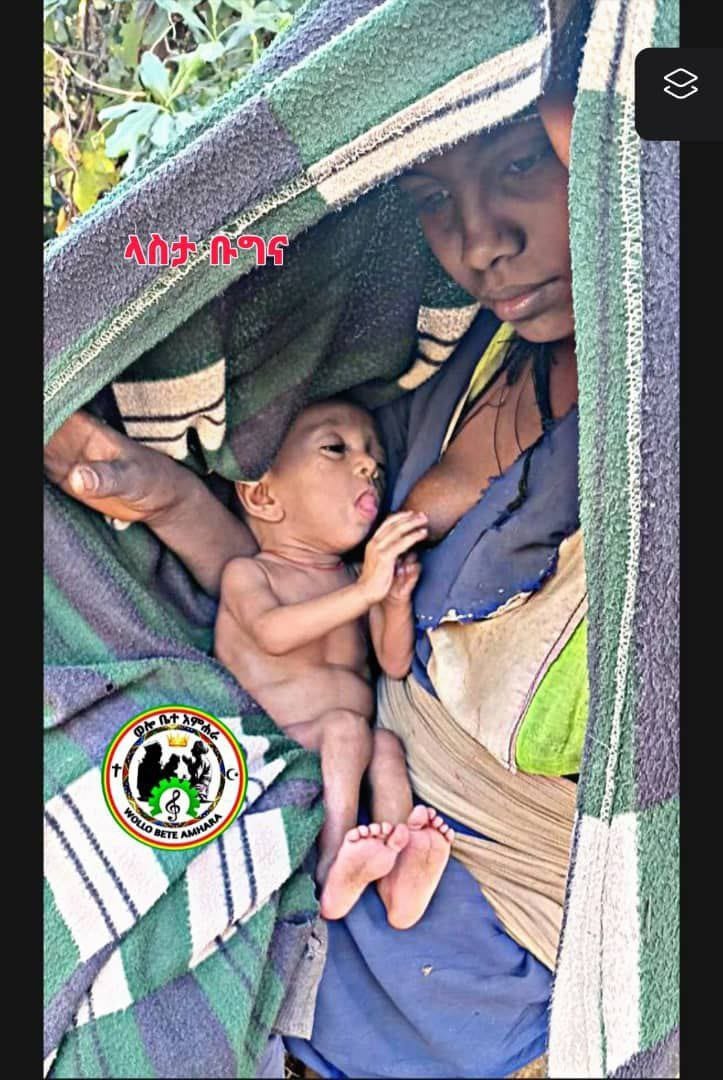

The affair recalled two related incidents that occurred in Muslims’ history of oppression in Ethiopia: major mass conversion incidents, one in Wollo and the other in the now Ethiopian Somali region.

The first occurred in the late nineteenth century when Emperor Yohannes IV forced Wollo Muslims to desert Islam in an edict that says “now, let all Muslim[s] be baptized [and] become Christian.” Emperor Haile Selassie I always sought the same but acted off the record through systematically institutionalized channels. And this transpired to be the worst oppression Muslims ever suffered. A circular letter disclosed that the State would be pleased to see “the Somalis embrace Baha’ism religion than they remained adherents of Islam.”

While the Dimtsachin Yisema resistance was part of peaceful struggle for all Ethiopians, the stories resonated much more strongly with the Ethiopian Muslims and in particular the young generation.

Despite the aggressive nature of the State’s approaches to impose a foreign sect on Ethiopian Muslims, the modus operandi they opted for to push back was remarkable. Unperturbed, wise, and strategically organized, the Muslims remained steadfast to the principles of peaceful struggle. In a few months, as happened in 1974, the Muslim’s peaceful struggle won the hearts and minds of a significant segment of the polity that seek serious change.

They were all supportive of the cause and its inspirational methods which encouraged them to build upon for more purely political causes. As the only enduring challenge against the police state since the 2005 national election, political leaders and analysts praised the resistance’s nature and acknowledged the key role it played in the run-up to the EPRDF’s demise.

Now, the House’s June decree to grant equal status is the best answer of all recent answers the Ethiopian State came up with in the modern history of its Muslim citizens.

Implications of the proclamation

Apart from the grand historical significance discussed above, the proclamation has other benefits worth highlighting.

Firstly, it jettisons the age-old and State-led securitization of Islam and Ethiopian Muslims by shining light on the historic longevity of Islam in the land, a history that the State should take pride in as it does with Christianity. It is a well-established historical fact that Islam as a religion came to this land only after Mecca, where it was revealed.

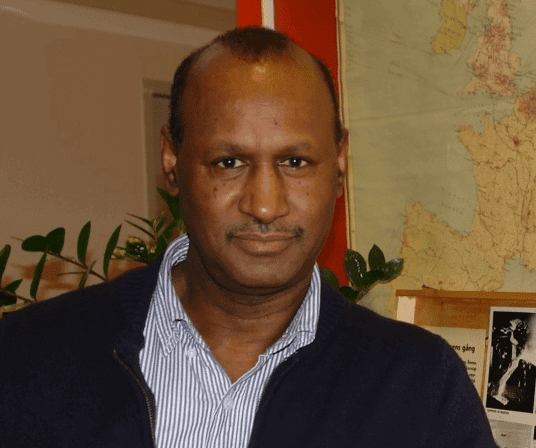

Academic Adam Kamil, who dedicates his life to studying and speaking about Ethiopia’s place and image in Islam, argues that Islam’s advent to Ethiopia equals justice. He asserts Ethiopia introduced the concept of treating migrants to the world 1,400 years ago. He suggested that this prototypical experience should be incorporated into the country’s broader history, if not utilized as a viable model in a global politics ridden by a refugee and migrant crisis.

Granting de jure equal status to its religions helps not only Ethiopian Muslims to proudly reclaim their rich history, but also helps the State reposition itself in world history that matches its antiquity.

Secondly, it glorifies Ethiopian Muslims as a religious society whose ontological existence is as old as the touching of Islam in Ethiopia.

The historical foundation of the Islamic community in Ethiopia is linked to the locals who welcomed members of the First Hijra and accepted Islam. Ethiopia’s contributions to Islam are ubiquitous in archives, yet its community and the State alike have no centrally administered collective ownership. The adoption of proclamation thus helps the Ethiopian Muslims remobilize and focus their efforts to re-identify themselves as a strong apolitical society rooted in its rich history, the State’s history.

Thirdly, the legal provision mirrors the magnitude of the present demography of Ethiopian Muslims. The significant proportion of Ethiopia as a polity is constituted by adherents of Islam. The number is such a large numerical value that deserves a parallel legal recognition through which apolitical activities of the society could be executed without facing legal hurdles and impediments by hostile officials.

Over the past several decades, even the majlis was subject to an annual renewal. The whole idea of going through such a complex institutional process undermined the grace of Ethiopian Muslims. But importantly, it practically precluded the majlis from behaving and functioning as a wider umbrella because this likens it with other NGOs whose organizational competence requires accreditation. The equal status provides the Ethiopian Muslims legal ground to see their umbrella spiritual organization differently from regular NGOs.

The last, semi-politically relevant point, is about ending a siege mentality.

Granting equal status to Ethiopian Muslims alters hostile mindsets and works against the perception of them as a threat. It deconstructs the legal and moral grounds that have been deployed by some agents, importantly the State and some regional states, to understand and treat Ethiopian Muslims as such.

The decree should serve as a key instrument for Ethiopian Muslims to reclaim their shared identity as an apolitical community. As an important precedent, the legal gateway should help Ethiopian Muslims come to a unity centered on their rich history, episteme, arts, and, crucially, their country, Ethiopia.