Children in the village of Wolenchite, Ethiopia play on solar-powered laptops provided by Boston-based nonprofit One Laptop Per Child.

SARATOGA SPRINGS (Desert News) — Ben Tanner and his wife, Jessica of Saratoga Springs, knew they were raising a budding hacker when they found their 4-year-old, Abe, in the basement playing “Angry Birds” on their Web-enabled TV. The Tanners were shocked. They don’t play “Angry Birds,” a popular video game in which players use a slingshot to launch birds into a pig pen. Twenty minutes alone in the basement, and Abe had turned on the TV, decided on a game and was launching birds with surprising accuracy.

Young children across the country are becoming skilled at manipulating gadgets they have never been shown how to use. Kids between 2 and 5 are more likely to know how to play computer games than swim or tie their own shoes, according to a 2010 survey of 2,200 mothers in the U.S., Canada and northwestern Europe by AVG, an Internet security company. It seems as if humans are born with a “natural” tendency to learn technology. And it isn’t just an American phenomenon.

Researchers at One Laptop Per Child, a nonprofit based in Cambridge, Mass., suggest that children in the developing world have the same technological intuition and appetite. Their research suggests these tendencies could be leveraged to provide education for more than 100 million children worldwide who do not have access to schools or teachers. Just playing around on an electronic device teaches these children essential literacy and critical-thinking skills that are the basis for economic development, according to Matt Keller, vice president of global advocacy at OLPC.

Toddlers and ‘Angry Birds: Africa’

OLPC’s goal is to provide learning opportunities for children in the poorest parts of the world. To do this it supplies kids with low-cost laptops preloaded with educational games. As tablet devices have become more popular, however, OLPC wondered if tablets might be a better teaching tool. “Tablets are more intuitive (than laptops),” Keller said. “You touch the screen, and something happens.”

To test the possibility of using tablets to educate children in the developing world, OLPC took devices to two remote Ethiopian villages without running water or electricity.

Wonchee, Ethiopia is one of the villages selected by nonprofit One Laptop Per Child to participate in a tablet pilot project.

Each child in the village received a tablet, which OLPC preloaded with English-based apps designed for children. Solar panels ensured they would never run out of power. Each device had a disabled wireless connection and camera. With parental permission, they tracked each child’s use.

It took four minutes for the kids in one of the villages to figure out how to turn their tablets on. Keller remembers the first kid to figure it out. “I thought he was developmentally disabled,” he said. “He didn’t look quite right and was painfully shy.” As the boy saw his screen light up, he yelled, “I am a lion!” in Amharic, Ethiopia’s native language. The other children swarmed around him, eager to find out how to make their tablets do the same.

By the end of the week, the children were using 57 apps per day. In the second week, they were learning how to recite and write the letters of the English alphabet. After several weeks, they’d also figured out how to unblock the camera and Wi-Fi. “They were using their devices an average of six hours a day,” said Keller.

Wolenchite, Ethiopia is one of the villages selected by nonprofit One Laptop Per Child to participate in a tablet pilot project

While it is not clear whether the children actually understood what they were doing, Keller said they had developed an awareness that certain sounds go with certain shapes. This is the foundation for literacy, explained Maryanne Wolf, a professor of child development at Tufts University who works with OLPC. More research is needed to determine if this is a viable strategy to give children who don’t have access to schools an opportunity to learn how to read. “If the learning can continue at the same pace we’ve seen,” said Wolf, “I just don’t know.”

Tablets against poverty

While it is still too early to know if these children will be able to become fully literate with no outside assistance, Keller, Wolf and the rest of the OLPC team are extremely optimistic. This is the kind of disruptive innovation that can “dramatically change educational opportunities for children in the poorest parts of the world,” Keller said.

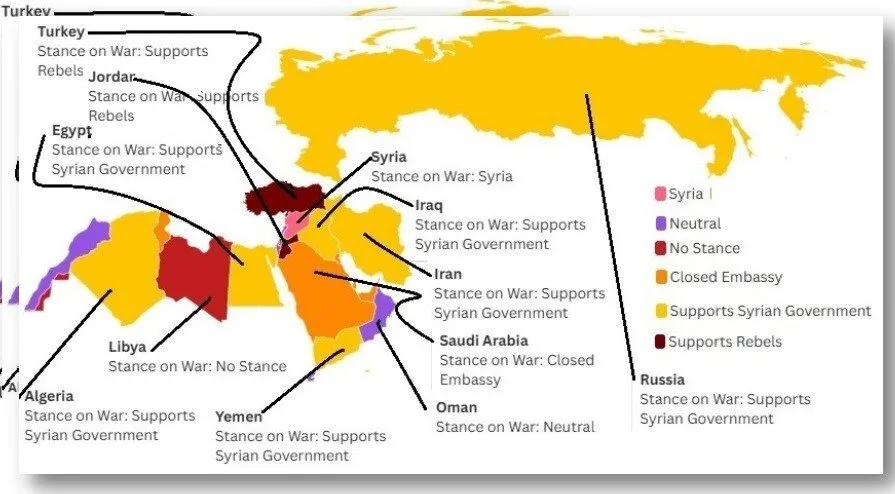

Literature on international development shows a strong correlation between literacy and economic development. Consider the disparate circumstances of neighbors Ethiopia and Sudan. In Ethiopia the literacy rate is 40 percent, according to World Bank figures. The per capita GDP is just $316. By contrast, Sudan has a 65-percent literacy rate and had a per capita GDP of $1,352 in 2008. While it is hard to establish a causal relationship, this isn’t a coincidence. In countries around the world there is a consistent connection: low literacy, low GDP.

OLPC’s founder is often quoted saying: “If a child can learn to read, he or she can read to learn.”

“Education is the absolute, unquestionable foundation of economic growth,” said Keller. “Too many kids never get a chance to fill their potential because they never get a chance to go to school.” If these devices can be used to “teach kids to read,” he added, “they can leapfrog the failed educational infrastructure around them.”

Replace the teachers?

OLPC has been criticized for trying to replace teachers with machines. The critics argue that without a teacher guiding the process there can’t be true learning. But, according to OLPC and other researchers doing similar work, their goal is not to replace teachers. Rather, they just want to bring learning opportunities to children who don’t have access to education.

“If you live in a part of the world where this isn’t a problem, you don’t need this solution,” said Sugata Mitra, professor of educational technology at Newcastle University in the UK in a 2010 TED Talk. “(Programs like OLPC) are for children who live in remote areas where there are no schools and no teachers or bad schools and bad teachers,” he added.

Wolf agrees with Mitra. “I don’t want technology to replace teachers, but where there are no teachers, or the teachers are overwhelmed, it can be helpful.” As a tool for learning to read, a tablet can help a child transcend the economic, physical and social barriers that keep them out of school, Wolf said.

“Literacy is the absolute bridge to release the potential of these kids,” she said. “We need to be doing everything possible never to neglect the potential of any children anywhere.”

Email: mwhite@desnews.com