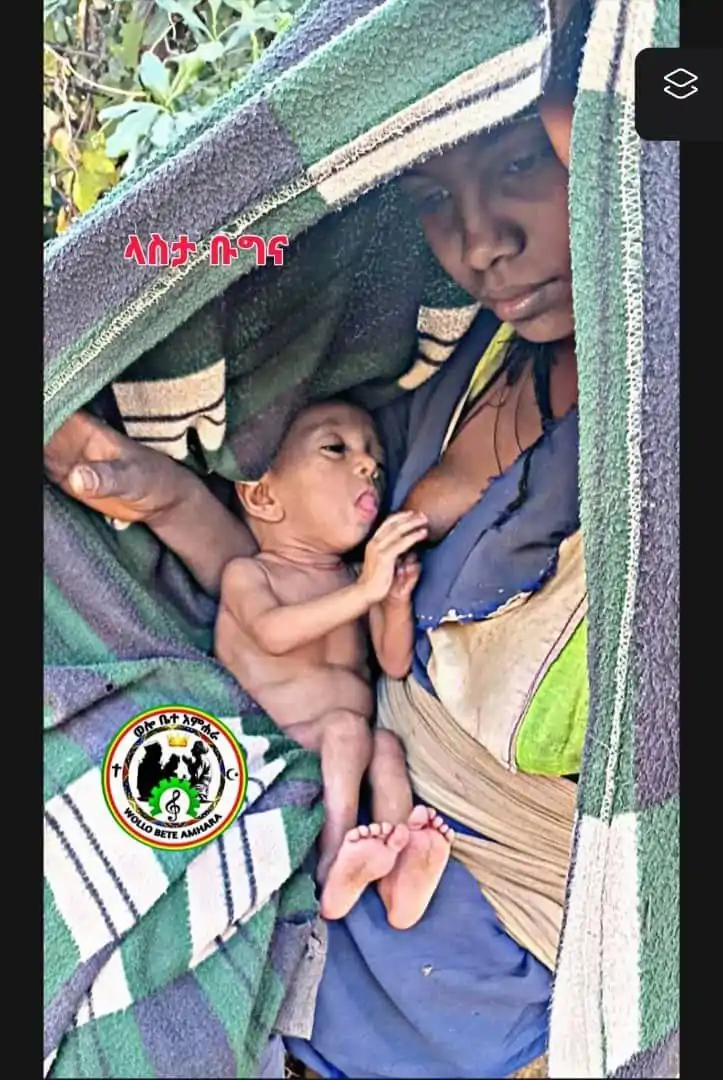

Internally displaced people who fled their homes in Berhale due to the fighting between the Afar Special Forces and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) stand near a makeshift compound, in Afdera town, Ethiopia, February 23, 2022. Malnutrition is rising in the region, said the U.N. World Food Programme, and Afdera’s camps are short of water, shelter and food. REUTERS/Tiksa Negeri

Internally displaced people who fled their homes in Berhale due to the fighting between the Afar Special Forces and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) stand near a makeshift compound, in Afdera town, Ethiopia, February 23, 2022. Malnutrition is rising in the region, said the U.N. World Food Programme, and Afdera’s camps are short of water, shelter and food. REUTERS/Tiksa Negeri

By Giulia Paravicini

AFDERA, Ethiopia (Reuters) – A new front in Ethiopia’s war in the Afar region is imperilling efforts to get enemies to sit down to peace talks, three regional officials and three diplomats said, and a ceasefire declared last week may have been breached in some places.

The flare-up of violence in Afar this year came after fighting in the neighbouring regions of Tigray and Amhara had ground to a stalemate and as moves were gathering pace to get the government in Addis Ababa and Tigrayan rebels to agree to peace negotiations.

“There cannot be peace in Ethiopia while there is fighting in Afar,” said Mussa Ibrahim, a clan leader in Erepti, one of six districts in Afar currently occupied by Tigrayan forces.

On Thursday, Ethiopia announced a unilateral ceasefire, the second to be called in a 16-month conflict that has displaced millions of people and plunged hundreds of thousands into famine conditions.

But Afar police commissioner Ahmed Harif told Reuters on Monday that fighting was ongoing in two of the six districts occupied by Tigrayan fighters, and there was a “significant” buildup of Tigrayan forces along the border.

Two humanitarian workers confirmed the fighting.

Getachew Reda, a spokesman for the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), which is battling the government, denied there were clashes in those areas. He did not comment on accusations of a military buildup.

The TPLF previously said it would observe the ceasefire if aid was speedily delivered.

The last time the government declared a unilateral ceasefire in July, following months of battles that forced the military out of Tigray, the TPLF dismissed it as a “joke” and continued fighting, saying key conditions for peace had not been met.

The TPLF and Afar forces dispute who started the most recent round of fighting in the northeastern region, which flared up in mid-January. The regional government estimates 300,000 people have had to abandon their homes.

The TPLF says they were responding to attacks on Tigray by Afar forces and allies, while Afar officials say Tigrayan forces were the aggressors.

Among those who fled the violence was Ayisha Ali, whose home town of Berhale came under attack in early February.

Speaking at a warehouse that serves as a rudimentary camp for the displaced in Afdera, some 130 km to the southeast of her home, she did not know what had happened to her seven children, after her family scattered amid the chaos.

Twelve other relatives were killed when their huts were struck by explosions, she said. Among them were her sister, her sister’s five children and a pregnant cousin. Ayisha blamed Tigrayan forces.

“We couldn’t even bury them; their bodies were in pieces,” she told Reuters. “The heavy weapons were firing at us, and we … ran away.”

Two neighbours, speaking at the camp, also described heavy fighting and civilian deaths. Reuters could not independently verify Ayisha’s or her neighbours’ accounts.

Getachew, the TPLF spokesman, did not respond to questions about the killing of civilians in Berhale and elsewhere in Afar. The group has previously denied targeting civilians.

TRADING BLAME

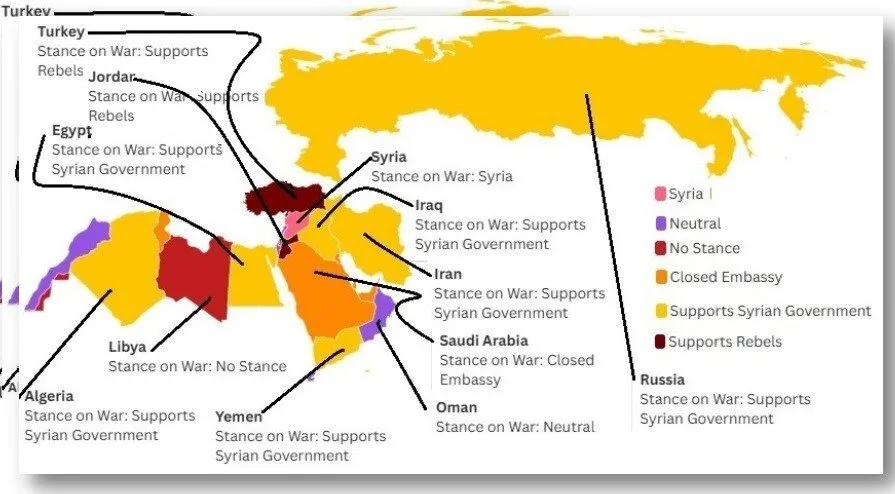

Tigrayan forces first entered Afar and the adjacent region of Amhara in July.

At the time, the TPLF said it was trying to break a stranglehold blocking aid convoys from entering the region and to force Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s Amhara allies to withdraw from a contested area in western Tigray.

A government offensive in December pushed Tigrayan forces back into their region.

This time around the warring parties dispute who initiated the violence, and the motives for it are less clear.

Ayisha described Tigrayan fighters arriving in Berhale on Feb. 7, sparking fierce gun battles with local militiamen involving heavy weaponry.

An internal United Nations security bulletin seen by Reuters said there was still fighting around the town on March 11-12.

The TPLF accuses Afar forces of attacking the Tigray region along with fighters from Eritrea, Ethiopia’s northern neighbour, which is also allied to Abiy’s government.

Eritrea’s Information Minister Yemane Gebremeskel did not respond to requests for comment on the TPLF accusations. In the early months of the war the country denied its forces were fighting in Tigray.

Afar regional officials, security forces and allied militiamen point the finger at the TPLF for opening a new front in the conflict.

“We don’t know why they are invading us, why they are killing our women and children,” said Mohammed Idris, head of Afar’s northern administrative zone. “We keep defending ourselves, as this is our land.”

Ethiopian government spokesman Legesse Tulu and military spokesman Colonel Getnet Adane did not respond to requests for comment about the fighting.

Mohammed Hussein, head of the government’s humanitarian aid office in Afar, said Tigrayan fighters returned to Afar in mid-January and now hold six out of the region’s 32 counties.

Getachew did not respond to questions about Tigrayan forces’ incursion.

The TPLF has accused Addis Ababa of stoking the conflict in Afar to justify blocking aid destined for Tigray, where more than 90% of the population needs food assistance.

Ethiopia’s government denies blocking aid and blames the fighting in Afar for cutting off the only route humanitarian convoys can take into Tigray.

The disputes underline how complicated it will be to end a war that has threatened the unity of Africa’s second-most populous nation.

The TPLF, which dominated Ethiopia’s government for nearly three decades before Abiy came to power in 2018, accuses him of trying to centralise power at the expense of the country’s ethnically based regions. Abiy’s government says the TPLF is trying to take back control of the country.

CIVILIANS KILLED

After Ayisha was separated from her children, who are aged between five and 18, she fled.

She said she and half a dozen other villagers walked eight days across the desert, begging passing herders for food and water. Two pregnant women who set off with them became too weak to continue. She does not know what happened to them.

Ayisha’s neighbour, Mohammed Mohamouda, said badly wounded people had been left behind in Berhale.

“There were many dead bodies. There was blood and body parts,” he said in an interview at the Afdera camp, where families lined up waiting for water.

At least 749 civilians have died in fighting in Afar and Amhara since July last year, including extrajudicial killings by all sides involved in the conflict, the government-appointed Ethiopian Human Rights Commission said on March 11.

On a trip to Afar in late February, Reuters saw two refugee camps overflowing with desperate families.

Malnutrition is also rising in the region, said the U.N. World Food Programme, and Afdera’s camps are short of water, shelter and food. Still people flood in.

Mohammed Hussein at the Afar aid office said the region was being overlooked by international aid groups.

“We need food, emergency shelter, water,” he said. “The international humanitarian community … has very little awareness or understanding about the Afar situation.”

The U.N.’s humanitarian arm OCHA said aid cannot reach some areas of the region due to fighting, and the whole effort is hampered by a lack of funds, supplies and partners.

A fifth of health facilities across Afar are not functional, OCHA said in a Feb. 24 report, because they are inaccessible or have been looted or destroyed.

Doctors at Dubti Referral Hospital, the region’s biggest located around 150 km south of Afdera, told Reuters it was running out of drugs and space as wounded and malnourished patients arrive.

The hospital’s chief executive officer Mohammed Yusuf said that around 300 people injured in the violence, including women and children, had arrived since January.

Cases of children wounded by unexploded ordnance or landmines have jumped from none to around 25 cases per week for the past two months, according to Tamer Ibrahim, head nurse for the surgical unit. Reuters saw medical records for 22 of these cases.

(Open https://reut.rs/3INQWYC to see a picture package)