Mengistu Musie (Dr) mmusie2@gmail.com

The national question in Ethiopia—concerning ethnic identity, self-determination, and state structure—did not originate solely from internal social and political dynamics. It was also significantly influenced and shaped by external forces, especially European colonial powers. Fascist Italy was among the chief of these powers. Its deliberate interventions laid the groundwork for ethnic divisions that were later politicized by various groups, including the Ethiopian student movement of the 1960s to the 1980s.

After Italy’s defeat at the Battle of Adwa in 1896, the country shifted its strategy. It moved fromopen military confrontation to more covert means of influence. Italy began presenting itself as a friendly nation and sent diplomats, military officers, and intelligence operatives under the guise of council generals and advisors. This period saw an increase in the number of European agents and researchers entering Ethiopia. Many were gathering intelligence and mapping the country’s ethnic and political landscape in preparation for future incursions.

Roman Prochaska, an Austrian national and Nazi Party member, exemplifies foreign actors whose work in Ethiopia during the late 1920s and early 1930s advanced fascist and divisive objectives. Although officially a lawyer in Addis Ababa, Prochaska’s real mission was intelligence gathering and ideological manipulation aimed at undermining Ethiopian unity. He openly disparaged Ethiopian culture—particularly the Amhara—and consistently articulated racist, contemptuous views about Ethiopia’s history and national identity throughout his long career.

Prochaska’s efforts in Ethiopia demonstrate the intentional European strategy to destabilize the Ethiopian state from within. By accentuating ethnic and regional divides, colonial agents like Prochaska worked to fragment the country and facilitate domination. These divisive narratives later shaped Ethiopian politics, notably influencing the mid-20th-century student movement’s debates on ethnicity, state power, and national unity.

Thus, the national question in Ethiopia cannot be fully understood without examining these early ideological incursions by European powers. The debates that gripped the student movement in later decades were, in part, the continuation of questions that had been deliberately introduced from the outside, with the aim of destabilizing one of Africa’s few enduring sovereign nations.

The National Question in ESUNA’s Early Debates (1969 –1971)

The Ethiopian Students Federation of North America (ESUNA) held its annual conference in Philadelphia in 1969 with a central focus on Ethiopia’s regionalism. Among prepared papers, Walelegn Mekonen’s thesis on the national question stood out for its bold arguments, igniting significant debate within the federation.

Two years later, in 1971, ESUNA revisited the same issue at its conference in Los Angeles, continuing discussions that began in Philadelphia.

At the Los Angeles conference, the national question once again dominated the agenda. This time, however, the debate centered almost exclusively on Walelegn’s paper rather than Tilahun Takele’s equally important writing on the national question, which he had prepared while in Algeria. As the conference progressed, the Senay Likie group staged a walkout in protest, while the majority of ESUNA members expressed support for Tilahun Takele’s thesis. This deepened divisions among Ethiopian progressives in North America, further revealing how polarizing the question of nationality and self-determination had become.

It is particularly striking, in retrospect, that the 1969 Philadelphia conference had already highlighted the challenges facing a multinational state such as Ethiopia. At that time, however, the majority of ESUNA members rejected Walelegn’s framing of the issue. Eritrean students, such as Haile Morkorios and Yordanos Gebre-Medhin, who were present at the conference, strongly disagreed with the majority position, as it failed to address their concerns. Yet by 1971, the situation had shifted dramatically. What was dismissed in 1969 gained traction two years later, as the majority of ESUNA members came to endorse Tilahun Takele’s thesis, which, in substance, aligned with Walelegn’s earlier arguments.

This reversal exposed the growing influence of the national question in shaping the student movement’s ideological orientation. Figures such as Meles Ayalew, who had criticized Walelegn’s framing of the issue as problematic in the 1969 congress, eventually walked out of the Los Angeles meeting when he saw the majority embrace the very thesis he had opposed.

Looking back, these conferences reveal not only the divisions within ESUNA but also the centrality of the national question to the broader Ethiopian student movement (ESM) in North America. The debates in Philadelphia and Los Angeles between 1969 and 1971 foreshadowed the fault lines that would continue to shape Ethiopian politics in the decades that followed.

Reflecting on the National Question

Looking back, one enduring issue for me is the national question of self-determination. First detailed by Lenin and later endorsed by Stalin, this principle defined key debates within Eastern progressive movements.

At the time, the national question and the principle of self-determination—up to and including secession—were historically justified. Much of the Global South, including countries such as China, was still under the grip of European colonial rule. In this context, the right to self-determination served as a legitimate and necessary tool for liberation, providing colonized peoples with a clear ideological basis to demand independence and dismantle imperial domination. The principle became both a political weapon and a moral justification for freedom.

However, when viewed in hindsight, what once seemed a straightforward and universally valid principle eventually became more complex. In the Ethiopian context, for example, the national question turned into a deeply divisive and even distracting element. Rather than serving as a unifying framework for liberation and development, it sowed discord among the progressive forces themselves. What was meant to be a tool of emancipation ended up creating confusion, particularly among some of the most educated and engaged people of our nation—those who came to feel that their primary identity was that of the “oppressed nationality.”

The tragedy is that the debate over the national question split movements, slowed down agreement, and led to competing claims of victimhood. Instead of uniting efforts for greater social and economic change, it became a battle of ideas that consumed more energy than it solved. This weakened progressive struggles from within. This dual legacy was valid and liberating during anti-colonial struggles. But in Ethiopia, without context, it was divisive and destabilizing. This remains one of the most significant lessons of modern history.

The Legacy of the National Question

The national question, first raised and championed by the radical student movements of the 1960s and 1970s, may have seemed at the time like a bold intellectual breakthrough. Yet, with the benefit of hindsight, it appears that what was once celebrated as a progressive idea gradually took on more complex consequences. What began as a theoretical debate among the “infantile students,” particularly within organizations such as ESUNA and ASUA, was later addressed by foreign powers interested in influencing Ethiopian politics for their own strategic interests.

Instead of consistently fostering unity, the national question sometimes provided a platform for division. It may have diverted attention from pressing tasks of modernization and collective growth, and in doing so, it contributed to challenges that included ethnic fragmentation. Ethiopian nationalism—once considered a unifying force for development and stability—was, at times, challenged by a growing emphasis on ethnic consciousness and identity.

The consequences have been significant. Ethiopia, a country with immense potential for progress, has often faced internal conflict—struggles not against foreign colonizers, but among its own people. What was intended as a liberating discourse has, over time, resulted in challenges, including fragmentation and mistrust.

Looking back, the once-confident students who believed they were laying the foundations of justice and equality now appear tragically mistaken. Their theories, while emotionally powerful, have proven deadly in practice. The very ideas they thought would free Ethiopia have instead become chains, binding the nation to cycles of division and conflict.

The lesson is sobering when ideology is adopted without regard for historical context and national cohesion; it can become not a tool for liberation but a weapon of destruction.

Looking Back at Mid-20th-Century Ethiopia

Let us look back at Ethiopia in the mid-20th century, a time of both success and hardship. During this period, the nation stood proud, having survived the cruelty of Fascism and Nazism in the Second World War and coming out with new dignity. The victory was not only military but also moral, demonstrating that Ethiopia—one of the few African countries never colonized—could resist and defeat foreign control.

At the same time, as Ethiopia celebrated its resilience, our Eritrean brothers and sisters raised their voices against European rule. United under the cry of “Mother Ethiopia or Death, and Unity!” they joined hands with southern compatriots in the struggle for freedom. From this unity emerged the Unionist Movement, led by prominent figures such as Tedla Bairu, Bitwoded Asfeha Gebre- Selassie, and Kes Dimitros. Their efforts triumphed, with the majority of Eritreans voting for unity with Ethiopia, reaffirming the bond of a shared history, culture, and destiny.

However, this shared victory of unity would not endure. In the years that followed, the children of that same generation rejected their fathers’ and mothers’ decisions. They abandoned the spirit of union and took to the mountains, carrying the banner of secession. The noble fight for unity thus tragically transformed into a protracted war of separation.

As a result, the most tragic chapter of all unfolded: a conflict that endured for thirty long years, pitting brothers and sisters of the same nation against each other. What had once been a united front against foreign domination devolved into internal bloodshed, weakening Ethiopia as a whole and leaving wounds that remain deep to this day. Behind the scenes, global and regional powers exploited the divisions for their own gain, fueling the flames of discord.

A moment of proud resistance to fascism and colonialism ended painfully in separation, showing how unity can break under internal and external pressure.

In examining the tension between majority rule and respect for minority rights—especially in multiethnic or multi-national states—I argue the best method for preserving human dignity, equality, democratic rights, and national unity is not to return to the 19th-century philosophy of the “national question.” Instead, we should consistently apply democratic principles. These principles should be universal in aim but adaptable to different circumstances.

Historically, the “national question” and the doctrine of self-determination—encompassing the right to secede—played significant roles in the anti-colonial struggles of the 19th and 20th centuries. These doctrines helped colonized peoples claim freedom from imperial powers and justified the formation of independent states where colonial rule was exploitative and foreign domination was evident. For example, such arguments were central during decolonization in Africa and Asia after World War II. Key thinkers, such as Lenin, argued that oppressed people have a bourgeois-democratic right to self-determination, including the right to secede from existing political structures.

The question of secession and its wrong results

In this regard, the armed movement initiated in Eritrea during the early 1960s was significantly influenced and supported by external actors. It was not a purely indigenous undertaking. Most Eritreans were organized under the banner of unity with Ethiopia—a motto emphasizing solidarity and continuity of historic ties. However, a few individuals broke away from this mainstream. Among them were Woldeab Woldemariam and others, who drew varying degrees of support from British colonial officials in East Africa and remnants of the Italian colonial establishment. These external powers, each motivated by its own strategic interests in the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa, encouraged division rather than reconciliation.

At the same time, Egypt and other Arab states openly opposed Ethiopian unity. This stance was primarily motivated by their geopolitical aim to limit Ethiopia’s power near the Nile’s source, as Egypt sought to secure control or influence over the Nile’s headwaters. As a result, these Arab states offered sympathy, resources, and political backing to Eritrean separatist groups, aiming to promote Ethiopian fragmentation and thus ensure greater leverage over Nile waters. This external support shaped the armed movement’s agenda toward secession over broader political reforms.

Meanwhile, in Ethiopia, Emperor Haile Selassie’s 1962 dissolution of the federal arrangement and annexation of Eritrea marked a major turning point. This act disregarded the will of the Eritrean people and violated the UN-brokered 1952 federation. The Eritrean armed movement did not demand restoration of the federation or meaningful democratic rights in a united Ethiopia, but instead pursued outright secession, reframing the struggle as one for national independence rather than equality or autonomy within Ethiopia.

The Eritrean armed struggle, rather than advocating for the restoration of democratic institutions and constitutional guarantees within Ethiopia, instead prioritized complete separation. This strategic shift, driven by Cold War politics and external interference, shaped the movement’s legacy. By abandoning the demand for federation and democracy in favor of secession, the movement directly contributed to decades of conflict and mistrust—legacies that still influence the region today.

Summary

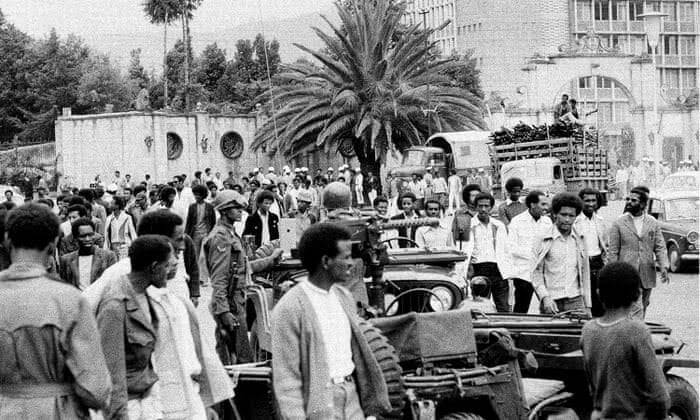

In conclusion, Ethiopia’s political trajectory has been shaped and sometimes distorted by waves of miscalculation and externally influenced agendas. The rise of the TPLF (Tigray People’s Liberation Front) and the OLF (Oromo Liberation Front) marked the introduction of armed struggles. Their divisive ideologies undermined the potential for a broad, democratic Ethiopian political system. At the same time, Mengistu Hailemariam’s military regime employed an oppressive and heavy-handed approach. This further alienated Ethiopians, stifling democratic aspirations and replacing authoritarian control with political exclusion.

Equally damaging was the vision promoted by secessionist movements and some segments of the student movement. They elevated the “national question” above the demand for democratic reforms. Rather than insisting on a system built on political equality, rule of law, and representative governance, they advanced agendas that fragmented Ethiopia along ethnic and regional lines. Ethiopia’s strategic rivals welcomed this outcome, as they have historically sought to weaken its unity and stability.

It is against this backdrop that today’s propaganda campaigns, such as Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s rhetoric about waging war for access to the Eritrean port of Assab, must be recognized as deeply misguided. Such war propaganda mirrors the reckless policies of the past. Mengistu Hailemariam’s violent interventions ultimately harmed the Ethiopian people rather than securing national strength. A war over Assab would not resolve Ethiopia’s challenges. Instead, it would perpetuate cycles of destruction, deepen mistrust with Eritrea, and open the door once again to external interference.

Similarly, the persistent intervention of Egypt and some Arab states in Ethiopian and Eritrean affairs is largely motivated by their own strategic interests in the Nile and the Red Sea. This remains a violation of the sovereignty and self-determination of both peoples. These external agendas thrive when Ethiopia and Eritrea are divided and in conflict. However, they do nothing to advance peace, prosperity, or regional cooperation.

Abiy Ahmed’s war rhetoric, Mengistu’s militarism, and secessionist ambitions all harm Ethiopians and Eritreans. What both people need is a return to democracy, inclusive government, and mutual respect. Only by rejecting war propaganda and foreign manipulation can Ethiopians and Eritreans build a future worthy of their sacrifices.