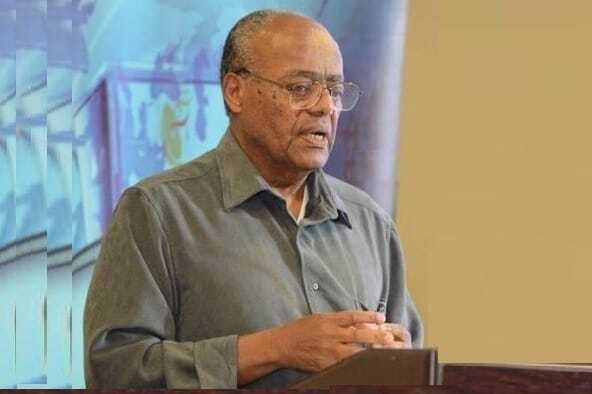

Messay Kebede

February 19, 2021

On the Support of some Western Circles to the TPLF

One thing that is as surprising as the swift military defeat of the TPLF is the support that it gets from some Western circles. In light of the TPLF’s abysmal record of human right abuses and the recent numerous atrocities it committed in the wake of its defeat, one would expect that the Western opinion would welcome the victory of federal forces with a sigh of relief. But alas, the expectation waned when officials from some Western governments started to echo the lies of the most ardent supporters of the TPLF of Tigrean and Western origins. Not only did the support ignore the recent extensive destructions and crimes committed by the organization, but it also attributed them to the federal government, even as it is beyond doubt that the TPLF started the confrontation and that no evidence taken on the ground corroborates the charge.

Ethiopians have been grappling to find some explanation for the positions that Western governments took. The prevailing opinion is that the federal government did not do enough both to inform the West about the origin and purpose of the war and to counter the lies and propaganda of Tigrean activists and their Western allies. To this explanation is added a second one, which is that the TPLF is using the complex and extended network of Western partnerships, mostly based on buyoffs, which network it was able to establish during its dictatorial rule over Ethiopia. The third reason has to do with a defining characteristics of the TPLF since its inception, namely, the culture of lies and deceptions, together with the cynical dictum that any means is good to achieve one’s end. Where a whole governing party and its numerous supporters have cultivated the art of lying with great skill and raised it to the level of most preferred political weapon, a point is reached when those who have lived in this bubble of lies for such a long time lose sight of reality. As a result, the lies can be told shamelessly and convincingly to the point that they can fool anybody. In the presence of such trained liars, the customary suspicion of the West can easily give way to downright gullibility.

I add a fourth explanation, which is that the TPLF, in presenting itself as a victim of an unprovoked aggression, has triggered the usual racist reactions of the West whenever crises occur in Africa. The hidden but entrenched stereotypes of barbarism and savagery quickly surface blocking all possibility of impartial assessment of the situation. All the more reason for the stereotypes to reappear is that the case involves a government and its citizens, which by definition means in Africa that the government is brutalizing innocent victims. Even though Nazi and Fascist regimes appeared and grew in the European soil, the long-held belief that barbarism is in the DNA of Africans takes over the interpretation of occurring events. It follows that violent stories about African governments need not be verified: such stories must have happened, as the contrary is unthinkable as a matter of sheer consistency. When similar stories occur in the West, they need to be investigated as they exhibit a deviance from the normal behavior. Not so in Africa, such stories are in the realm of what is to be expected.

The Politics of Leverage

Sudan’s incursion into and occupation of Ethiopian territories is the other event that took most Ethiopians by surprise. Various explanations were and are still advanced in an attempt to make sense of this sudden military aggression, even as negotiations over border demarcation were still underway and that no side indicated that the talks had broken off.

The first explanation that jumps to mind refers to the ongoing military operation in Tigray. Seeing that Ethiopian federal forces are quite busy defeating the TPLF’s numerous and well-equipped militia forces and pacifying Tigray, and perhaps even drawing the implication that Ethiopian military capability has been weakened as a result, the Sudanese government concluded that the opportunity to recover claimed lands is too good to pass up. The second explanation points to the internal turmoil that is shaking Sudan. What better opportunity to appease the protests and the divisions within the political elite than to stir up the nationalist sentiment under the guise of recovering territories illegally appropriated by Ethiopia? Unsurprisingly, the higher echelon of the Sudanese military apparatus took the initiative of the invasion, with the obvious hope that it will reinstate the lost hegemony of the military over their civilian partners.

The third reason involves Egypt and the dispute over the Nile dam. It is argued that the Sudanese military leadership has always had close relationships with the Egyptian military leaders. So that, Egypt’s opposition to the dam offers the good opportunity to renew the much sought-after ties. Putting enough pressure on the Ethiopian government could either delay the construction of the dam or make Ethiopia more accommodating to Egypt’s demands. The payoff for siding with Egypt will be all the more rewarding for both countries the more the negotiations over the dam turn into a match of two against one. All things considered, Sudan’s interest is best served when it sides with Egypt.

I have no doubt that all these reasons have contributed to the decision to invade the Ethiopian territory. Still, they seem to take one thing for granted, namely, that Sudan is indeed ready to wage war against Ethiopia and has come to the conclusion that it can prevail militarily. All the reasons enumerated to account for the Sudanese decision are also reasons liable to infuriate the Ethiopian people and government, with the consequence that war becomes inevitable. I believe that neither side really wants this outcome. Then what on earth did the Sudanese government expect to gain by invading Ethiopia?

Without dismissing the option of military confrontation, the Ethiopian government has consistently made the resumption of talks conditional on the Sudanese withdrawal to its previous official borders. It is understandable that it does not want to jeopardize its victory over the TPLF by moving quickly its troops out of Tigray. Equally reasonable is the thinking that, if war is inevitable, it must be waged with the full capacity of the Ethiopian military if one is to avoid the perpetuation of indecisive skirmishes that will only weaken it. In short, the best option for the Ethiopian government is to buy time. Hence my question: is time on the side of Ethiopia?

My thinking is that the Sudanese military leadership decided to invade the territories by betting on the unwillingness of the Ethiopian government to respond militarily to the invasion. Its guiding idea is that Ethiopia is in dire need of the good will of the Sudanese government. Neither the situation in Tigray will stabilize nor will the negotiations on the Nile dam go in its direction if Ethiopia does not have the support of the Sudan. Some such leverage must translate into a payoff for Sudan, which is that Ethiopia, however reluctantly, must accept the colonial demarcation of the two countries, the very one drawn in 1903 by the British surveyor, Major Gwynn, without the consent of the then government of Ethiopia. In other words, the Sudanese government is not asking for a military confrontation with Ethiopia; rather, it is blackmailing Ethiopia for its assistance in pacifying Tigray and solving its problems with Egypt in terms favoring its wishes.

Since the main purpose of the invasion is to provide Sudanese military elite with a nationalist aura so as to give it an edge in its competition with its civilian counterpart for the control of power, I have difficulty believing that the threat of war or diplomatic pressures can be effective in obtaining a withdrawal to previous positions. The decision to back off would constitute a heavy blow to the political ambition of the military. Unless there is a major political shakeup in Sudan or the Ethiopian government secretly surrenders to the blackmail––a possibility I personally discard––war seems, therefore, inevitable. Such an outcome would be little surprising: as reconfirmed by what happened in Tigray, wrong calculations of the possible reactions of the other side have triggered most wars.

I contend that Ethiopia and Sudan find themselves in a similar situation: the flawed calculations of one side leads to a war that neither side really wants. As Friedrich Engels said speaking of the manner history unfolds, “there are innumerable intersecting forces, an infinite series of parallelograms of forces which give rise to one resultant — the historical event.” So that, “what each individual wills is obstructed by everyone else, and what emerges is something that no one willed.”

In sum, the above analyses call attention to the fact that the case of Tigray and that of Sudan are closely connected. The Sudanese invasion would not have occurred without the TPLF’s insurrection in Tigray. The final pacification of Tigray also depends in some measures on the friendly or unfriendly attitude of the Sudanese government. And if we involve here Egypt, as we should do, it becomes clear that war against Sudan would just be an extension of the war in Tigray. History repeats itself: internal disputes have always been a gateway to external foes.

https://udayton.academia.edu/MessayKebede

Messay Kebede is a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Dayton in Ohio. He is the author of several books and articles, including the acclaimed book, Survival and Modernization–Ethiopia’s Enigmatic Present: A Philosophical Discourse.