Our concern: promises mean little if local people see no gains.

This introduction looks at community benefits, fair revenue sharing, and why honoring a chief builder from the Amhara Region matters. We will examine how GERD can deliver electricity, jobs, and infrastructure to the Blue Nile basin—and how to make that delivery real. Above all, we reflect on the legacy and responsibility tied to Engineer Simegnew Bekele.

The Vision Behind GERD

The vision behind GERD (Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam) is deeply rooted in Ethiopia’s ambition to transform itself into a powerhouse of Africa. For many Ethiopians, GERD is far more than an energy project—it is a symbol of national pride, economic progress, and a break from poverty and energy scarcity. GERD is seen as a way to ensure energy independence for Ethiopia, enabling the country to provide electricity to millions still living without power and export energy to neighboring countries. This vision also includes fostering regional integration through shared prosperity. Leaders and the public have expressed hopes that GERD will help create a stronger nation, reduce reliance on foreign aid, strengthen industries, and tap into the vast potential of the Blue Nile. It is also viewed as a statement—an assertion of Ethiopia’s right to utilize its natural resources for development, after centuries of watching others benefit while it struggled.

Key Features and Construction Timeline

Key features and the construction timeline of GERD highlight its massive scale and technical significance. GERD is set on the Blue Nile River in Ethiopia, about 30 kilometers upstream from the Sudanese border. Its installed capacity is about 6,450 megawatts, making it Africa’s largest hydroelectric dam and one of the largest worldwide. The dam stands approximately 145 meters high and stretches 1.8 kilometers across the river, forming a reservoir with a capacity of 74 billion cubic meters. Construction began in April 2011 and major milestones include the initial filling of the reservoir in 2020 and continued works up to 2024. The project faced several funding, engineering, and diplomatic challenges but pushed forward, driven by popular fundraising and government resolve. GERD’s design also includes features to manage sediment, generate reliable hydropower, mitigate seasonal floods, and expand irrigation potential, indicating a clear emphasis on both technical excellence and broad utility.

Political Context and Regional Water Rights

The political context and regional water rights issues make GERD one of the world’s most controversial dams. The Nile is a lifeline for Ethiopia, Sudan, and especially Egypt, which relies almost entirely on Nile waters for its agriculture and survival. For decades, colonial-era treaties favored Egypt and Sudan, strongly limiting Ethiopia’s share. GERD’s construction disrupted the regional status quo, creating a tense dispute over water rights. Egypt fears the dam could reduce the flow of water during the filling period or droughts, potentially devastating its economy and food security. Sudan sees both risks and opportunities, as the dam could improve water management but also complicate downstream supply. Ethiopia, however, asserts its right to development and fair share of the Nile. The ongoing negotiations, UN Security Council debates, and power struggles between these nations have turned the GERD into a symbol of both hope and conflict, highlighting complex questions of international law, sovereignty, and resource justice.

Social and Environmental Impact

The social and environmental impact of GERD is vast and still evolving. Socially, the dam has sparked national unity in Ethiopia, with millions contributing to its funding and public workers donating salaries. It promises significant improvements in access to electricity, health, and education, and has already inspired many with a sense of national achievement. However, there are also concerns—large-scale infrastructure projects can displace local populations, as seen with rural communities near the reservoir who may lose their land and traditional livelihoods. Environmentally, the dam is built to capture 100 years’ worth of sediment, which could reduce erosion downstream and affect natural flood cycles. Experts warn of possible negative impacts, such as reduced water quality, loss of some types of biodiversity, and changes to the natural flow of the Nile, affecting the livelihoods of people in Sudan and Egypt. The dam’s large reservoir will also alter habitats and could increase waterborne diseases if not carefully managed. Sustainable policies, cooperation with affected communities, and transparent environmental monitoring will be essential to address these concerns and ensure GERD brings fair benefits to both people and nature along the Nile.

The Legacy of Engineer Simegnew Bekele

Early Life and Background

Engineer Simegnew Bekele was born on September 13, 1964, in the small town of Maksegnit, once part of Begmeder Province, which is now within the Amhara Region of Ethiopia. He grew up in a farming family, which helped him understand the value of hard work and the importance of Ethiopia’s natural resources. From a young age, he showed great interest in science and engineering. He eventually studied civil engineering at Addis Ababa University, where he excelled in his classes and graduated with strong technical knowledge. This educational background set the stage for his career in Ethiopia’s vital infrastructure development.

Rise to Project Leadership

Rise to Project Leadership

Simegnew Bekele’s rise in Ethiopia’s infrastructure sector was marked by dedication and a track record of delivering important projects. Before taking on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), he was involved in other major engineering works, such as the Gilgel Gibe I and II hydropower projects. His performance and technical skills caught the attention of Ethiopian Electric Power Corporation (EEPCo), where he became highly respected for his ability to plan and execute large-scale constructions. Because of his proven leadership and expertise, he was appointed as the first Chief Project Manager of GERD, making him the public face and leader of Ethiopia’s largest and most ambitious national project.

Architect of Ethiopia’s Mega Project

As the chief engineer and project manager for GERD, Simegnew played a foundational role from start to finish. He took on the responsibility of planning, organizing, and supervising one of the most complex hydropower dam projects in Africa, which has the capacity to generate over 6,000 megawatts of electricity. Bekele managed resources, coordinated teams of thousands of workers, and dealt with both technical and political challenges. His commitment to Ethiopian development made him an architect, not just of the GERD structure itself, but also of a new era for Ethiopian infrastructure, focused on self-reliance and national pride.

Leadership Style and Engineering Intellect

Simegnew Bekele’s leadership style was one of determination, humility, and clear communication. He earned trust by working alongside laborers, listening to expert engineers, and always explaining the importance of the dam to the Ethiopian people during public events and media interviews. He was known for his tireless work ethic—often spending long hours on-site in challenging conditions. His approach combined deep engineering knowledge with a people-first attitude, which motivated and united teams from different backgrounds. Many saw him as both a technical genius and a symbol of hope for Ethiopian progress.

Challenges and Triumphs on GERD

During the construction of GERD, Bekele faced many serious challenges. Political tensions with neighboring countries, especially Egypt and Sudan, created international pressure. There were technical delays, funding difficulties, and harsh working environments. Despite these problems, he led his team to major milestones, such as the completion of key phases of the dam. Under his supervision, the project stayed on track even when external forces tried to derail it. Every triumph at GERD—such as the first filling of the reservoir—was a testament to his resilience and leadership.

Legacy in Ethiopian Infrastructure Development

Simegnew Bekele’s legacy is deeply tied to Ethiopia’s future as an energy-independent nation. The GERD is now a symbol of national strength and hope for economic transformation. Bekele’s influence goes beyond the dam itself—he inspired a generation of Ethiopian engineers and leaders. Through his work, he set a new standard for project management and technical excellence in Ethiopia. His life and tragic death left a mark on the nation. Today, his legacy is reflected in every kilowatt generated by GERD, in the improved lives of Ethiopian people, and in the spirit of self-made progress he helped ignite.

The Blue Nile’s Historic Role for Ethiopia

The Blue Nile, or Abay as it is called locally, has deep roots in Ethiopian history and heart. The river begins its journey at Lake Tana and is seen by Ethiopians as a divine gift and part of their national identity. For centuries, the Blue Nile has represented hope and sustenance for communities living along its banks. Ancient Ethiopians worshiped the river and relied on its floods for fertile soil needed for farming. Despite being the main source of the Nile’s water, Ethiopia historically could not use much of this resource because of past colonial treaties and regional power struggles. The river’s flow has also shaped Ethiopia’s relationships with downstream neighbors, especially Egypt and Sudan.

Economic Potential for Local Communities

The economic potential of the GERD on the Blue Nile can be transformative for local communities. Many villages near the river have long suffered from poverty and lack of basic infrastructure. Local people have struggled with unreliable rainfall, absence of electricity, and limited job opportunities. With GERD, there is now hope that reliable hydropower will be made available, bringing electricity to millions who live off the grid. This spark of progress is expected to attract industries, boost irrigation, and create markets for local farmers. Real GDP gains for Ethiopia are expected to reach nearly 7 billion USD, benefitting not just cities but rural towns as well. Still, there are concerns the benefits may not be evenly distributed unless there is real commitment to local development, investment in roads, schools, and health centers.

Addressing the Resource Curse in the Blue Nile Basin

Addressing the resource curse is a big challenge in the Blue Nile Basin. The “resource curse” means that even if a place is rich in natural resources, its people can stay poor due to weak governance, conflicts, or outside interference. In the past, the Blue Nile has sometimes felt like a curse: the water flowed out, but little benefit came back to local Ethiopians. The ambition with GERD is to finally convert this curse into a blessing. With responsible management, the dam could deliver not just power, but also better roads, water supply, schools, and job opportunities for the basin’s residents. However, there is concern that without transparency and open participation, powerful interests might capture the largest share of the dam’s benefits, repeating old mistakes.

Grassroots Participation and Social Justice

Grassroots participation is vital for true social justice in the GERD project. In Ethiopia, people at all levels contributed money and support for the dam, seeing it as a symbol of national pride. For social justice to be real, those who live near the dam and have endured displacement or environmental changes must have a say in how benefits are shared. Direct participation increases accountability, making it harder for powerful actors to take all the profits while ordinary people remain poor. Social justice in the Blue Nile basin means access to electricity, fair compensation for communities affected by flooding, and investments in public goods. It also means recognizing the rights and dignity of Indigenous people along the river, who have sometimes been forgotten. When people see real change in their daily lives—schools, clinics, electricity—they are more likely to trust and support the project.

Benefits for the Amhara Region and Beyond

The benefits from GERD ought to flow first to those in the Amhara region and neighboring areas who share the river’s burdens and risks. With the arrival of electricity, local businesses can grow, health centers can work without interruption, and children can study at night. This region is also poised for improved ecosystem protection, as regulated water flow can prevent both destructive floods and droughts. However, some in the Amhara region worry that despite the promise, they are not yet seeing their fair share of the rewards. Ensuring the GERD’s gains reach local populations and not just the central government or foreign investors is a matter of justice. Only then will GERD become not just a national achievement, but also a true blessing for communities who have long waited for the river’s promise to be fulfilled.

Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia—The Nile Water Dispute

Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia remain deeply divided over the waters of the Nile, with the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) at the heart of tensions. Egypt relies on the Nile for over 90% of its freshwater, and views the GERD as an existential threat. Egyptian leaders have often demanded a binding agreement from Ethiopia before the dam is fully operational, worrying about reduced water flow and major impacts on agriculture and industry. Sudan, caught in between, has shifted its stance several times, sometimes taking Egypt’s side, sometimes leaning towards Ethiopia based on its domestic interests.

Ethiopia sees GERD as its right and an essential development project. For Ethiopia, the dam is a symbol of sovereignty and the ability to use its natural resources for economic progress and for lifting millions out of poverty. However, the dispute has resulted in years of failed negotiations, rising rhetoric, and involvement of international actors. The basic conflict is about how future droughts will be handled and who controls the water flow, with fears that the dam could be used as political leverage. If not managed well, the Nile water dispute has the worrying potential of sparking broader instability in the region.

International Pressure and Solidarity in Ethiopia

International pressure over GERD has been intense, with powers like the United States, the African Union, and the Arab League calling for new talks and mediation. Egypt has frequently appealed to international forums, including the UN Security Council, to push Ethiopia for a deal. Many Western nations and multilateral organizations have urged Ethiopia to show more flexibility and warned about potential conflict.

Despite these pressures, there is strong solidarity in Ethiopia. The population broadly rejects outside meddling, viewing international criticism as unfair and siding overwhelmingly with the government’s approach to the GERD. Ethiopians have funded much of the project through domestic bonds and donations, creating a sense of unity and ownership. Even as external actors try to influence negotiations or impose diplomatic costs, many ordinary Ethiopians see these pressures as attempts to deny their basic development rights. This has only deepened the country’s determination to see the project completed.

Protecting Ethiopian Interests and Resources

Protecting Ethiopian interests and resources is central to Ethiopia’s GERD policy. The country’s leaders argue that for decades, colonial-era agreements favored Egypt and Sudan while ignoring Ethiopia, where the majority of the Blue Nile’s water originates. GERD represents a move to correct this historic imbalance, with promises to use the dam to generate power, manage floods, and improve water management.

Ethiopia also stresses its responsibility to avoid any significant harm to downstream countries. Yet, Ethiopians widely believe they must safeguard their own future first, using GERD as a tool for poverty reduction, industrial growth, and greater regional influence. Many Ethiopians see the project as a shield against economic dependency, and as a lasting legacy for the next generation. The focus remains on defending national interests, pushing for equitable resource sharing, and ensuring that Ethiopian voices shape how Nile water is used.

The role of Public Support and National Pride

Public support and national pride are the engines driving the GERD project forward. Across Ethiopia, people donated salaries, bought bonds, and made personal contributions to fund GERD when international loans were unavailable due to opposition or hesitancy from lenders. The dam has become a symbol of unity, resilience, and national achievement. People see GERD as a testament to what Ethiopians can accomplish through self-reliance and hard work.

The pride is rooted not only in building Africa’s largest hydroelectric dam, but also in standing up for Ethiopia’s rights in the face of global and regional criticism. Popular culture, media, and even songs celebrate GERD as a unifying national project. Leaders often invoke GERD when rallying the public or defending the nation’s sovereignty. The power of this public support makes the dam not only a technical or economic feat, but also a point of collective pride and determination to protect Ethiopia’s interests on the world stage.

Honoring Engineer Simegnew Bekele’s Legacy

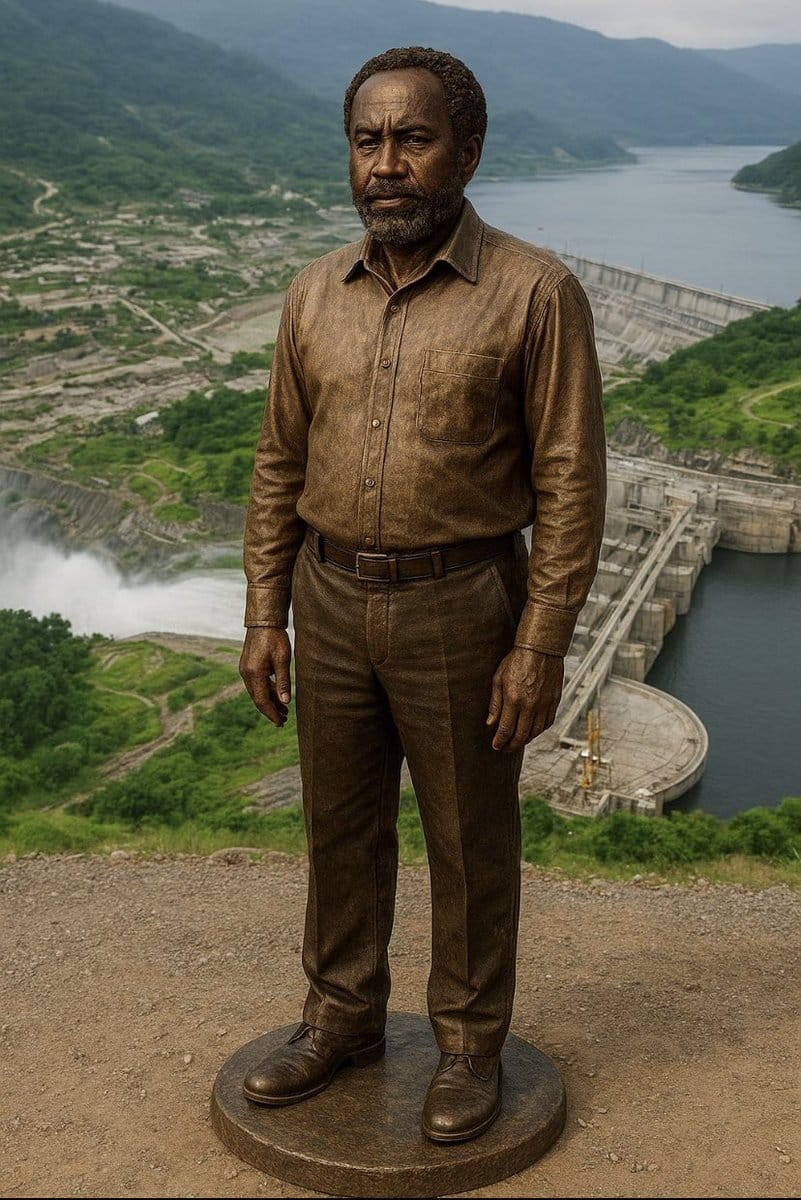

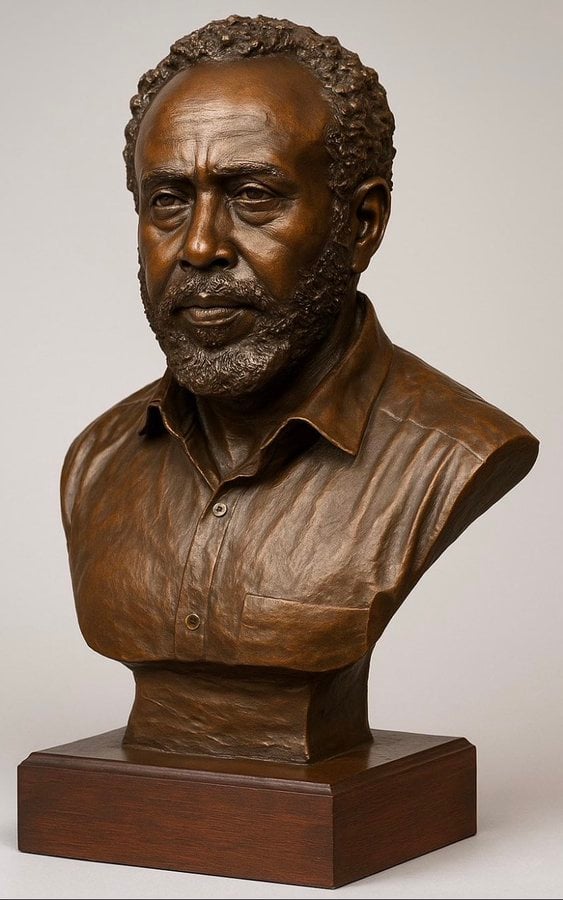

Calls for National Recognition and Monuments

Calls for national recognition of Engineer Simegnew Bekele grow louder every year. Ethiopians from different regions agree that his work on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) deserves a lasting tribute. People want statues, parks, and public spaces named after him. Some communities have already started local initiatives, while national leaders discuss bigger commemorations. Building physical monuments is seen as a way to inspire the next generation. Many believe that honoring Simegnew helps keep the story of GERD alive, showing young people how much a single determined engineer can achieve for the whole country.

Memory, Martyrdom, and Public Mourning

Memory of Simegnew Bekele is still very fresh in the minds of Ethiopians. When news of his tragic death spread, the country was covered in sadness. Thousands gathered in the streets, holding candles, crying, and paying their respects. Some consider him a martyr, as he gave everything—including his life—to see GERD succeed. There are many stories and songs, especially in Addis Ababa and the Amhara region, remembering his dedication. Every year, people remember the day he died. Social media fills with his quotes and photos, showing how much he meant to the people. This public mourning has made Simegnew more than just an engineer; he is seen as a national hero who led by example.

His Vision for Equitable Resource Distribution

His vision for equitable resource distribution was one of Simegnew’s guiding principles. From the earliest days of the GERD project, he spoke about using Ethiopia’s water and land in a fair and just way. He believed that the dam should help all regions, not just a few. Simegnew wanted GERD to give affordable electricity to villages and small towns as well as big cities. He argued that no community should be left out, especially the rural and poor areas. His speeches often focused on unity and equality, making sure that every Ethiopian saw GERD as “their” project. This vision helped earn the trust of workers and local leaders.

Ensuring Benefits Reach the Grassroots

Ensuring benefits reach the grassroots was always close to Simegnew’s heart. He knew that large projects sometimes leave rural communities behind. To avoid this, he pushed for programs that brought jobs, roads, and schools to the people living near the dam. He also wanted local voices to be heard in important decisions. Since his passing, many still worry that these goals could be forgotten. Community leaders and civil society groups now call for transparency in fund use, simple rules for sharing power, and training new engineers from rural backgrounds. Real change will happen only if these grassroots benefits become real and visible, just as Simegnew dreamed. His legacy demands that GERD not just power cities, but transform lives in every corner of Ethiopia.

Sustainable Management of the Blue Nile Basin

Sustainable management of the Blue Nile Basin is absolutely crucial for the future of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Experts warn that lack of strong sediment management and ongoing land degradation could shorten the dam’s lifespan and hurt its energy potential. Reports from scientific and hydropower organizations point out that the GERD is designed to trap sediment for up to 100 years, but that climate change and poor upstream land practices could increase sediment loads and risks.

Therefore, effective water management strategies, such as integrated basin management and consistent monitoring of sediment inflow, are essential for GERD’s sustainability. Careful reservoir management not only assures power generation but also improves drought protection and water availability both upstream and downstream. Failing to protect the Blue Nile Basin could undermine the project’s long-term benefits for Ethiopia and its neighbors.

Environmental Rehabilitation and Protection

Environmental rehabilitation and protection tied to GERD is a growing concern for the region. Official reports and news articles highlight that GERD presents both opportunities and risks for local ecosystems. On the positive side, GERD can help balance river flows, restore natural habitats, and support reforestation efforts in areas affected by deforestation and degradation.

Research suggests targeted landscape-based regeneration projects can efficiently revive ecological zones harmed by human activity and past environmental neglect. But there’s also a risk that improper planning or lack of investment in ecological restoration could allow further habitat loss and poor biodiversity outcomes. The consensus is that responsible operation of GERD must include funding and support for environmental protection programs and regional cooperation on climate resilience. Ethiopia must not neglect environmental stewardship if it wants GERD’s benefits to last for future generations.

The Need for Community Involvement and Oversight

The need for strong community involvement and oversight in GERD’s next chapter is urgent. While the dam is a grand achievement for the Ethiopian nation, local communities along the Blue Nile and those most affected by resource allocation and social impacts need a real voice. Recent discussions by Ethiopian civil society organizations have emphasized that people’s rights and well-being must be protected as GERD becomes fully operational.

Meaningful grassroots participation in decision-making and monitoring activities helps ensure fair benefit distribution and sustainable resource use. Without transparency, oversight, and ways for affected groups to raise concerns, there’s a real risk of marginalization or unintended negative impacts. Oversight committees, public forums, and civil society engagement are essential tools for safeguarding GERD’s social contract.

Ensuring Accountability in Revenue Distribution

Ensuring accountability in GERD revenue distribution is a serious and persistent issue. Major reports and policy studies note that with such a large national project, there’s always the risk of corruption or unfair allocation of funds. Ethiopia’s leadership and stakeholders must set up transparent systems that make sure revenue from GERD’s electricity generation flows back to the citizens, especially those communities who sacrificed their land or livelihoods.

Effective revenue distribution requires regularly audited reports, clear rules for how income is shared, and anti-corruption safeguards. If the public perceives that the profits from GERD are being misused or diverted, trust in the project will collapse. Building trust is possible only with ongoing accountability and equal opportunities for all Ethiopians to benefit from GERD’s success.

The Role of the Amhara Community in GERD’s Future

The role of the Amhara community in GERD’s future is critical. As one of the communities most closely connected to the Blue Nile Basin and its resources, Amhara people have a deep stake in the dam’s legacy. Many news outlets and analysts argue that recognizing the Amhara community’s contributions, concerns, and leadership is central for GERD’s long-term stability.

Amhara voices must be at the table in management, oversight, and benefit-sharing decisions. Ignoring this could cause local grievances and undermine national unity. By involving the Amhara—and all affected communities—in meaningful dialogue and giving them a share in the benefits, Ethiopia can build a brighter, more inclusive future for all who rely on the Nile’s life-giving waters.

This approach not only honors past sacrifices, but also creates a sustainable path for future generations to thrive.

Completing GERD—Technical, Political, and Social

Completing the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) has come with many technical, political, and social challenges. Technically, building one of Africa’s largest dams on the Blue Nile required cutting-edge engineering skills and advanced project management. The dam has faced logistical issues, such as sourcing high-quality materials and dealing with difficult terrain. At certain points, construction slowed due to unexpected technical setbacks and supply interruptions, showing how complicated such a megaproject can be.

Politically, GERD remains a hot topic between Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan. Negotiations about how much water each country can use have often ended without agreement. Egypt sees the dam as a threat to its water supply. Sudan worries about water flow and dam safety. Ethiopia, on the other hand, views GERD as a symbol of national pride and a path to energy security. This regional disagreement has drawn in the African Union, the United Nations, and even global powers, leading to tense diplomatic moments.

Socially, GERD has inspired huge national support in Ethiopia, with the public funding a significant part of construction costs. Yet, there are concerns about relocating communities and the long-term impacts on people living near the project. Managing the expectations and fears of the local population, as well as downstream communities, is a challenge that overlaps with technical and political issues.

The Role of Young Engineers and Leaders

The GERD project has shown the importance of young engineers and leaders in Ethiopia’s development. The new generation of Ethiopian engineers has played critical roles in both the design and construction phases. These young professionals worked side by side with veterans, gaining hands-on experience in large-scale hydropower projects.

Their involvement goes beyond technical skills. Many young engineers and local leaders have become passionate advocates for the dam, organizing campaigns to raise funds and build solidarity. Their work is a model for how the youthful population of Africa can step up to address huge national challenges. Many of these young professionals are now prepared to guide future infrastructure projects, not only in Ethiopia but throughout Africa.

Blueprint for African Resource Management

GERD is a blueprint for African resource management. The project was planned, funded, and managed mostly by Ethiopians themselves, showing the power of local ownership. Unlike many previous mega-projects on the continent, Africans have led all key decisions about design, operation, and distribution of benefits.

GERD’s regional impact also highlights the need for transboundary cooperation. Experts agree that water projects like GERD can only succeed if countries share resources fairly. The dam has brought global attention to “African solutions for African problems”. This means prioritizing peaceful dialogue and involving all stakeholders. If managed well, GERD could inspire other African nations to take bold steps to manage their own natural resources, invest in local talent, and build infrastructure that benefits more than just the elite.

Lessons From Ethiopia’s Largest National Project

Many lessons can be learned from the GERD project. First, strong public ownership and pride can make even the biggest dreams possible when combined with transparent management. Ethiopians’ willingness to fund GERD through local contributions is unmatched in the region.

Second, the dam teaches us about the value of equitable resource sharing and cooperation. Disputes between Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan underline the need for honest negotiation and legal frameworks when dealing with transboundary rivers. Fair use agreements are essential to avoid conflict and promote regional stability.

Third, the GERD shows that environmental and social consequences must be carefully managed alongside technical success. Resettlement of local communities and changes in the river’s ecology are long-term issues. If ignored, they can become bigger problems in the future.

Finally, GERD’s story proves that local expertise is crucial. Building this massive dam with mostly Ethiopian engineers and workers is a testament to what communities can accomplish when they invest in science, education, and teamwork. Future African projects should look to GERD not just for power, but as a symbol of innovation, unity, and determination.