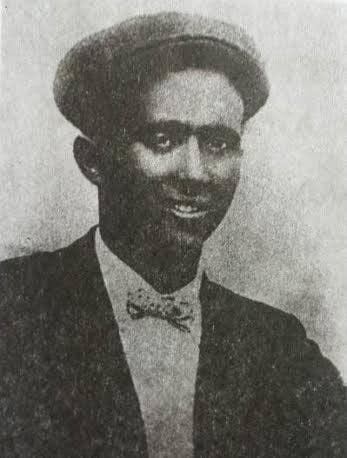

Who was Gebrehiwot Baykedagn, and why does his short life still worry us today? Born near Adwa, Tigray, he rose from hardship to become an Ethiopian doctor, economist, and intellectual. In a country facing famine, unjust taxation, and slow change, his voice pressed for urgent reform.

Educated in Europe, he returned to serve Menelik II and later Haile Selassie, working on the Addis Ababa–Djibouti railway and in customs. He argued for economic modernization, administrative reforms, and the abolition of slavery. His key works—Atse Menelik na Ethiopia (1912) and the posthumous Mengistna ye Hizb Astadadar (1924)—helped shape early development economics in Ethiopia.

This biography will trace his early life, education, government service, main ideas, and legacy, asking what we can learn from Gebrehiwot Baykedagn today.

Early Life and Background

Birth and Family Origins

Gebrehiwot Baykedagn was born in 1886 in the village of May Mesham near Adwa, in the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia. His family was known for its scholarly and clerical background. Specifically, his father Baykedagn was respected in the region and served in the palace of Emperor Yohannes IV. However, Gebrehiwot’s life would soon be marked by tragedy as his father died serving the Emperor at the Battle of Matamma. This meant that from a very early age, Gebrehiwot would face the difficulties of growing up without a father, shaping the determined and thoughtful person he became.

Childhood in Tigray and Eritrea

Childhood for Gebrehiwot Baykedagn was spent between Tigray and the Eritrean highlands. After his father’s death, he grew up in a period marked by instability and uncertainty. For the first seven years of his life he lived at a Swedish mission in Eritrea, which became an unexpected turning point for him. The mission provided a very different atmosphere compared to his birthplace, exposing Gebrehiwot to new ideas and cultures. Life around Adwa and Eritrea during those years was deeply affected by ongoing conflict and hardship, but the mission environment offered moments of safety and education.

Impact of the Great Ethiopian Famine

The Great Ethiopian Famine of the late 1880s had a direct and painful impact on Gebrehiwot Baykedagn. The famine, which destroyed countless lives across Tigray and other parts of northern Ethiopia, left families in hunger and despair. Gebrehiwot, as a child, saw the devastation caused by hunger and disease. It pushed him and others to seek refuge and assistance from places like the Swedish mission. This tragic disaster marked a critical moment in his early years, as he saw the limits of traditional support systems and the pressing need for new ways to solve big social problems. His later drive for reform and modernization was rooted in witnessing the horrors and suffering of famine first-hand.

Encounter with European Missionaries

During these difficult years, Gebrehiwot’s life intersected with European missionaries, particularly at the Swedish mission in Eritrea. The missionaries gave him shelter, food, and a first glimpse into European education and medicine. Their influence was profound, introducing him to another way of thinking about religion, science, and society. This exposure began to spark Gebrehiwot’s life-long interest in learning, modernization, and reform. The friendships he built with missionaries would change his destiny, opening the door to opportunities that most Ethiopian children of his generation could hardly imagine.

Journey to Europe and Adoption

Gebrehiwot Baykedagn’s journey to Europe stands out as a remarkable turning point. As a young boy, he managed to travel with friends to the port of Massawa. There, he and his companions found passage on a German ship, which took them first away from Africa. Upon arrival in Europe, fate smiled on Gebrehiwot when the ship captain arranged for him to be entrusted to a wealthy Austrian family. This family formally adopted him, a rare twist of fortune for an Ethiopian child in that era. Adoption by this family was the key to introducing him to a European household and its educational system, giving him opportunities that were unavailable at home.

Education in Austria and Germany

Education became the anchor of Gebrehiwot’s new life in Austria and later in Germany. With the support of his adoptive family, he quickly learned the German language and adapted to the European ways of life. He was able to enroll in advanced schools and eventually pursue university studies. His academic focus was medicine, but he also became deeply interested in administration, economics, and the modern sciences. The lessons Gebrehiwot learned in Austria and Germany would later become central to his efforts to reform Ethiopia. Living and studying in Europe made him realize both the weaknesses and strengths of Western thinking, as well as the urgency to bring some of these modern ideas back to Ethiopia to help his homeland avoid the kind of suffering he had witnessed as a boy.

Medical Studies at Berlin University

Medical studies at Berlin University were a significant part of Gebre-Hiwot Baykedagn’s education and set the stage for his later career in Ethiopia. While in Europe, he did not simply learn about Western medicine; he gained a deeper understanding of modern scientific practices and European institutions. According to academic sources, Gebre-Hiwot attended the University of Berlin and pursued rigorous instruction in medicine, which exposed him to the critical thinking and analytical problem-solving approaches favored by European academics at the time. This medical training would later inform his deep concern for public health and systemic reform in Ethiopia. Many modern historians note that it was this exposure to science and rational methodologies that shaped his push for modernization and bureaucratic reform upon his return home.

Diplomatic Experiences and Language Skills

Diplomatic experiences and language skills were a defining feature of Gebre-Hiwot’s professional formation. He was deeply involved in diplomatic efforts; for instance, he led Ethiopia’s 1918 trade mission to the United States on behalf of Empress Zewditu. This position required not just diplomatic tact but also fluency in multiple languages, acquired during his education and travels in Europe. His broad linguistic capability included Amharic, Tigrinya, German, French, and likely some English. This multilingualism enabled him to communicate directly with foreign officials, scholars, and business people, thus giving Ethiopia a clearer voice on the global stage. His writing is praised for its clarity and purity of language, reflecting his mastery not only of content but of expression — a skill that enhanced both his diplomatic work and intellectual output.

Exposure to European Thought and Modernization Theories

Exposure to European thought and modernization theories changed the trajectory not only of Gebre-Hiwot’s life but of Ethiopia’s reform movement. While in Europe, he encountered ideas about scientific modernization, bureaucratic rationality, the role of the state in development, and social contracts that were gaining ground in Germany and Austria. He saw firsthand how European societies used education, technological innovation, and structured government administration to rapidly advance. Unlike simple imitation, Gebre-Hiwot critically assessed whether these ideas could fit within the Ethiopian context, blending what he saw as practical from Europe with his own vision for Ethiopia’s future. Ethiopian and international scholars agree that his unique perspective—at once appreciative and critical of European models—allowed him to advocate for modern reforms while remaining deeply rooted in his home country’s realities.

Gebre-Hiwot Baykedagn’s academic and professional formation in Europe provided not only skills and knowledge but also an outlook that valued rational, merit-based governance essential for Ethiopia’s survival and growth. This period made him one of the most important intellectuals to stand at the crossroads between indigenous tradition and global modernity.

Role as Interpreter for Emperor Menelik II

Gebrehiwot Baykedagn’s return to Ethiopia after his education in Europe marked a new era in his career. One of his first important roles was serving as a private secretary and interpreter for Emperor Menelik II. Because he was fluent in several European languages and had a deep understanding of Western customs and thinking, he was quickly trusted with high-level communication between Ethiopia and foreign powers. At a time when the country’s interactions with Europeans had grown much more complex, Gebrehiwot’s abilities helped Emperor Menelik II communicate diplomatically and navigate the changing world stage. He was not just a translator—his position also meant he was an advisor, helping Menelik grasp the intentions and meanings behind foreign visitors’ words. His critical role is often connected to Ethiopia’s emerging position as an independent African state after the defeat of Italian forces at Adwa.

Aftermath of the Battle of Adwa: Influence on National Policy

Gebrehiwot Baykedagn’s service to the Ethiopian state came as Ethiopia sought to strengthen itself after the critical victory at the Battle of Adwa. The triumph over Italy protected Ethiopia’s sovereignty, but it also brought new challenges. Gebrehiwot’s experiences in Europe gave him a unique perspective, and he became involved in national policy, especially around modernization and international relations. He believed that Adwa’s victory should lead not only to pride but also to hard work in building a better, fairer country. As a thinker and policy advisor, he pushed for reforms in Ethiopia’s political and economic systems, using Adwa as proof that Ethiopia could—and must—stand alongside the world’s nations as an equal. He worked on treaties and border agreements that followed Adwa, helping make Ethiopia’s independence internationally recognized.

Service in the Courts of Menelik II and Lej Iyasu

After Menelik II’s health declined, Gebrehiwot continued public service in the royal courts, including under the leadership of Lej Iyasu. His work became more prominent as a policy strategist and reform advocate. While his background was in medicine, his influence spread to the highest circles of government. Under both rulers, he was respected for his broad education and his willingness to challenge the old ways of thinking. During Lej Iyasu’s turbulent reign, Gebrehiwot tried to push forward reforms, but court politics and suspicion of “foreign ways” made his work difficult. Even so, he remained a strong voice for progress, justice, and openness to new ideas—qualities that weren’t always welcome by the traditional elites.

Inspector of the Addis Ababa–Djibouti Railway

Gebrehiwot Baykedagn’s commitment to progress was also seen in his work as Inspector of the Addis Ababa–Djibouti Railway, the most vital transportation project in Ethiopia at that time. This railway project was a symbol of Ethiopia’s drive for modernization and economic growth, aimed at connecting the country to the outside world and boosting trade. As the inspector, Gebrehiwot oversaw its operation and maintenance, ensuring it served Ethiopia’s needs efficiently. His management helped make the railway a success, supporting both government and private trade. The skills and standards he demanded set an example of how Ethiopia could manage complex projects using modern methods.

Nagadras (Chief of Commerce and Customs) in Dire Dawa

Another important post for Gebrehiwot was his role as Nagadras, or Chief of Commerce and Customs, in Dire Dawa—one of Ethiopia’s most active trade cities due to its position on the railway line. Here, Gebrehiwot was responsible for controlling imports and exports, collecting customs duties, and overseeing trade regulations. Dire Dawa was a crucial lifeline for the Ethiopian economy, and Gebrehiwot’s administration made efforts to root out corruption and ensure smooth, fair trade. His policies aimed to make trade more transparent and efficient, laying groundwork for economic stability. His time as Nagadras reflected his strong belief that good governance and strong institutions were the keys to a better Ethiopia, ideas he continued to communicate through both his actions and writings.

Gebrehiwot Baykedagn’s years in public service had a lasting impact on Ethiopia, showing both the promise and the struggles of real modernization. His positions—from interpreter to railway inspector to Nagadras—allowed him to apply his vision, but also showed him the difficulties of changing an old society.

Intellectual Contributions and Major Works

Overview of Key Writings

Gebrehiwet Baykedagn’s intellectual legacy rests on his two classic works, which helped shape Ethiopian social and political thought. His first major book, “Atse Menelik na Ethiopia” (1912), gives insight into the reign of Emperor Menelik II and Ethiopia’s transformation during a critical period. His second, “Mengistna ye Hizb Astadadar” (1924), published after his death, explores the relationship between state and people, offering a deep analysis of what a modern Ethiopian government should look like. These writings have not only influenced Ethiopian intellectuals but continue to be studied by those interested in African modernization, governance, and development.

“Atse Menelik na Ethiopia” (1912)

“Atse Menelik na Ethiopia,” written in Amharic and later translated into French, is a vital resource for understanding the political and social changes during Menelik II’s era. Gebrehiwet used this work to highlight Menelik II’s reforms, Ethiopia’s resistance to European colonialism, and the drive to modernize the country. He described Menelik as a leader aiming to unify Ethiopia and introduce new institutions, while also critiquing the resistance Menelik faced from traditional elites and religious conservatives. The book blends historical narrative with social analysis, making it a cornerstone for Ethiopian modern history.

“Mengistna ye Hizb Astadadar” (1924)

“Mengistna ye Hizb Astadadar” (which translates as “Government and Administration of the People”) is considered Gebrehiwet’s most influential piece. This work, published in 1924, is sometimes translated into English as “State and Economy of Early 20th Century Ethiopia.” In it, he analyzes the shortcomings of Ethiopia’s governing systems and proposes rational bureaucratic structures, fair taxation, and new ways for state and society to work together. Gebrehiwet argued for modern civil administration, accountability, and policies aimed at economic progress. His work challenged the old ways of feudal privilege and stressed the importance of merit-based governance.

Analysis of Governance: “Government and People”

In “Government and People,” Gebrehiwet offers a detailed critique of traditional Ethiopian governance and calls for change. He examines how the state and its rulers have often been separated from ordinary people, leading to inefficiency, corruption, and public distrust. Gebrehiwet believed a modern nation required a rational, effective government system, where leaders are chosen for their abilities and where the state listens to the needs of its citizens. He stressed that good governance means serving the people, not just ruling over them. This analysis remains relevant for understanding issues of leadership, bureaucratic reform, and democracy in Ethiopia.

Economic Philosophy and Modernization Proposals

Gebrehiwet’s economic thinking was grounded in his vision for a modern, developed Ethiopia. He believed the country needed to move away from subsistence and feudal economies and embrace, instead, policies that would promote industrialization, merit, and innovation. He favored the creation of skilled labor, modern technology, and strong infrastructure—pointing to countries like Japan as positive examples. Gebrehiwet warned against falling into the trap of foreign domination and advocated selective borrowing from the West to protect Ethiopian sovereignty.

Critique of Oligarchy and Traditional Systems

A major concern for Gebrehiwet was the oligarchic structure of Ethiopian society. He strongly criticized the aristocracy and regional warlords, who clung to power and used the state for personal interest. He saw this oligarchy as blocking progress, keeping ordinary people in poverty, and stopping the growth of new ideas. According to Gebrehiwet, true progress could not happen unless Ethiopia broke away from its reliance on a small, privileged class.

The State as a Voluntary Association

Gebrehiwet suggested that the state should not be something forced on people. Instead, he viewed the state as a voluntary association, in which citizens agree to be governed under fair laws because the government serves the public good. This was a radical idea for his time, especially in a society based on kingship and privilege. Gebrehiwet’s view hints at early democratic thinking, where the people are not simply subjects, but active members of their own political destiny.

Equitable Taxation and Land Distribution

One of Gebrehiwet’s most important proposals was his call for fair taxation and land reform. He saw how uneven land ownership and heavy taxes on the poor were holding Ethiopia back. He proposed a system where taxation would be based on the real value of assets, and land would be distributed more equitably. His aim was to reduce poverty and social inequality, helping create a strong foundation for national development. Gebrehiwet’s arguments still speak to Ethiopians today, as the country continues to debate land, tax, and fairness.

Gebrehiwet Baykedagn’s writings are a testimony to his deep concern for Ethiopia’s future and his commitment to justice, progress, and modernity. His legacy lives on in debates about governance and development across Africa.

Social and Economic Reforms Advocated

Calls for Bureaucratic Rationalism

Calls for bureaucratic rationalism were a major part of Gebre-Hiwot Baykedagn’s philosophy. He believed that Ethiopia could not progress without creating a clear and effective government system managed by skilled officials. In his writings, Gebre-Hiwot criticized the old ways, where power was based on family connections or favoritism rather than knowledge and skill. He wanted the government to be guided by clear rules, with jobs given to capable people. According to him, rational bureaucracy would help to reduce corruption and disorder. This approach was inspired by the efficiency he saw in European and Japanese governments. By promoting qualified workers and clear processes, he believed Ethiopia could build a stronger and more modern state.

Abolition of Slavery and Feudal Privileges

Abolition of slavery and feudal privileges was central to Gebre-Hiwot’s reform agenda. He deeply disliked Ethiopia’s dependence on slavery and the huge power held by local nobility. In his view, these institutions kept the people poor and divided. Gebre-Hiwot argued that to lift Ethiopia out of backwardness, it was vital to grant all people equal rights and protect them from exploitation. Ending slavery, he said, was necessary for both moral and economic progress. Likewise, breaking feudal privileges would let the government use resources more wisely and allow ordinary people a say in their country’s future. For him, social equality was not only fair but also the foundation for meaningful national development.

Vision for Education and Skilled Labor

Vision for education and skilled labor was another hallmark of Gebre-Hiwot’s proposals. He saw the lack of schools and proper training as a big obstacle for Ethiopia. Gebre-Hiwot wanted education for all citizens, not just sons of the elite. He supported modern schools teaching science, languages, and technical skills, believing this could prepare Ethiopians to compete in a changing world. By building a skilled labor force, he hoped to fill government offices with able workers, create new industries, and encourage innovation. For him, education was the key to breaking the cycle of poverty and pushing Ethiopia forward.

Emphasis on Infrastructure and Technology

Emphasis on infrastructure and technology featured strongly in Gebre-Hiwot’s writings. He observed that lack of roads, railways, and telecommunication made Ethiopia fall behind other countries. Gebre-Hiwot wanted the government to put money into building roads, bridges, and railways, connecting regions and helping trade. He also urged the adoption of new technologies, such as telegraph lines and modern agriculture tools. By improving infrastructure, Gebre-Hiwot hoped to bring markets closer to farmers, speed up communication, and make daily life easier for ordinary people. He saw these changes as necessary for economic growth and social unity.

Japanese Model: Administrative Efficiency and Innovation

Japanese model of administrative efficiency and innovation fascinated Gebre-Hiwot. He often mentioned Japan as proof that a non-European nation could modernize quickly without losing its culture. Gebre-Hiwot admired how Japan combined old traditions with smart reforms. He wanted Ethiopia to learn from Japan’s careful planning, investment in education, and promotion of talented people to government jobs. By copying some features of the Japanese system—such as strict training of officials, clear laws, and focus on progress—he believed Ethiopia could shape its own path to modernization. For Gebre-Hiwot, the Japanese example showed that progress was possible for Ethiopia, as long as it had the right vision and leadership.

Barriers to Ethiopian Modernization

Banditry, Militarism, and Corruption

Banditry, militarism, and corruption have long been major barriers to Ethiopian modernization. Banditry made travel dangerous and disrupted trade, making it difficult for people to move goods or spread new ideas. Militarism meant the country spent large resources on keeping power through force rather than building better schools, roads, or hospitals. Corruption was a serious problem because officials often took bribes instead of doing their jobs fairly. These three problems together kept the country stuck in old ways and stopped progress toward a more modern society. People feared losing their land, their freedom, or their lives, making them less willing to try new things or support reforms.

Unjust Taxation and State-Finance Separation

Unjust taxation and the weak separation between state and personal finances were also big obstacles. The tax system was unfair, putting a heavy burden on poor farmers while letting the rich and powerful avoid paying their share. This discouraged people from working hard because they saw no reward for their efforts. State officials often used public money for their own needs. There was no clear line between the money that belonged to the country and what belonged to the rulers. This hurt trust and made it almost impossible to plan for the future or invest in public services. As a result, modernization plans had very little support, and people remained trapped in poverty.

The Struggle for Meritocratic Governance

The struggle for meritocratic governance was another key issue. In theory, a merit-based system would allow the most skilled and knowledgeable people to take important jobs. But in Ethiopia, positions of power were often given to those with family connections, wealth, or loyalty to a leader rather than to those with real talent. This led to poor decision-making and inefficiency. Smart and ambitious people were frequently ignored or pushed aside. Without a true meritocracy, the government could not use new ideas or move the country forward quickly. Many projects failed because the wrong people were in charge, wasting both time and resources.

Cultural Resistance and Elite Opposition

Cultural resistance and elite opposition made modernizing even harder. Some traditions encouraged respect for elders and the past, but also made people afraid of change. Elders and powerful families worried that new policies or technology would threaten their authority. Elite groups often resisted modernization because it might mean losing their privileges, lands, or easy incomes. Even ordinary citizens sometimes feared that new ways would break their connection to Ethiopian identity. These deep-seated attitudes made it difficult to introduce reforms, even if they offered clear benefits to most people. Change came slowly because powerful groups used every tool available, from spreading rumors to direct violence, to delay or stop progress.

Influence on Ethiopian Intellectual History

Gebre-Hiwot Baykedagn’s influence on Ethiopian intellectual history is both deep and far-reaching. He is widely seen as a pioneer in Ethiopian social and economic thought. His works, especially “Mengistna ye Hizb Astadadar,” introduced systematic social analysis and bold reform proposals at a time when such thinking was new in Ethiopia. Unlike previous writers, Gebre-Hiwot called for a practical approach to modernizing administration, economy, and education, blending local understanding with lessons from his studies in Europe. Later Ethiopian thinkers and reformers, especially those concerned with governance and national development, have cited Gebre-Hiwot as an inspiration. Many modern intellectuals honor him for showing that it was possible to mix Ethiopian challenges with global ideas.

Reception by Contemporary Scholars

Contemporary scholars have viewed Gebre-Hiwot Baykedagn as both a visionary and a controversial figure. Many praise him as Ethiopia’s first true development theorist. Works such as Putting Gebrehiwot Baykedagn (1886-1919) in Context and other academic reviews highlight his sharp critique of the feudal aristocracy and his push for reforms like merit-based bureaucracy, abolition of slavery, and fairer taxation. However, some scholars argue that his strong admiration for European models sometimes overlooked local realities. Despite this, his careful analysis of Ethiopia’s social problems remains basic reading for anyone studying Ethiopian history and policy. The founding of research centers in his name reflects his continued importance among Ethiopia’s modern thinkers.

Enduring Relevance to Development Economics

Gebre-Hiwot Baykedagn’s economic ideas still hold major value today. He is recognized as a pioneer of development economics in Africa. His focus on bureaucratic efficiency, skill-building, land reform, and technology predicted many issues in later Ethiopian development debates. His understanding that successful development needs institutional reform and education is now a standard belief worldwide. Several academic papers note that Gebre-Hiwot’s call for home-grown solutions—such as adapting foreign models to the Ethiopian context—remains a powerful lesson for today’s policymakers. His model of using economic knowledge, skill, and innovation as engines of progress continues to shape thinking about development in Ethiopia and throughout Africa.

Debates Over Eurocentrism vs. Indigenous Vision

Debate continues around Gebre-Hiwot’s use of European ideas versus his commitment to an Ethiopian vision. Some critics say he was too Eurocentric—relying heavily on Western examples and under-valuing local traditions and strengths. This has sparked discussions about whether his solutions were imposed from outside or adapted from within. However, other scholars defend Gebre-Hiwot as a pragmatic reformer. They argue he used European ideas not out of worship but because he wanted proven tools for a struggling country. Gebre-Hiwot’s work wrestles with these tensions, making him both a source of inspiration and a focus for debate about the best road to modernity for Ethiopia.

Lessons for Ethiopia’s Ongoing Challenges

Gebre-Hiwot Baykedagn’s work is still vital for Ethiopia’s current challenges. He understood that true progress required strong, educated institutions and fair government—vital problems that Ethiopia continues to face. His warnings against corruption, tribalism, and weak administration sound very familiar today. Modern scholars and reformers draw lessons from his clear advice: modernize boldly but wisely, respect Ethiopia’s unique qualities, and always put public interest above selfish power. Ethiopia’s struggles with governance, conflict, and underdevelopment show that Gebre-Hiwot’s insights were ahead of their time. If his advice had been followed more closely, Ethiopia’s history might have seen fewer wasted years. The country still has much to learn from this lost reformer.

Circumstances of Death in 1919

Circumstances of Gebre-Hiwot Baykedagn’s death have remained a source of sorrow and frustration for many Ethiopians. According to Wikipedia and several scholarly sources, Gebre-Hiwot died in Dire Dawa, Ethiopia, on July 1, 1919, at the age of only 33. His death was sudden and is often described as “premature” in both academic articles and public discussions. At the time of his passing, he was serving as inspector of the Addis Ababa–Djibouti railway, a key infrastructural project symbolizing his commitment to modernization. Despite the general respect he had earned, the Ethiopian state did not fully embrace his bold ideas, and he passed amid a period of national uncertainty following intense political shifts after Emperor Menelik II’s reign. There are no widely reported stories of foul play, but the shock of losing such a promising and gifted reformer so young has haunted Ethiopia’s intellectual memory.

Reflection on a Short but Impactful Life

Reflection on Gebre-Hiwot Baykedagn’s life always circles back to his amazing productivity and insight despite his short years. He was not just a thinker but also an active reformer in Ethiopian society. By age 33, he had published two major books, served in various important government roles, and challenged entrenched systems of feudalism and backwardness. Sources such as ResearchGate and academia.edu note that his work laid the groundwork for later generations of Ethiopian intellectuals, influencing debates on bureaucratic rationalism, meritocratic governance, and modernization. He promoted critical thinking, urged the end of slavery, and called for equitable taxation and land distribution—all while insisting that Ethiopia could modernize without giving up its cultural identity. Even though he worked in a highly traditional and resistant political environment, Gebre-Hiwot proved that thoughtful analysis and urgent reforms were possible and necessary. His legacy endures as that rare example of a reformer who was ahead of his time, not just for Ethiopia, but for Africa in general.

The Warning Ethiopia Ignored

The warning that Ethiopia ignored is the most painful part of Gebre-Hiwot Baykedagn’s story. In his writings—such as “Atse Menelik na Ethiopia” and “Mengistna ye Hizb Astadadar”—he repeatedly cautioned that the slow pace of reform, coupled with the dangers of corruption, arbitrary rule, and backward economic policies, would bring future hardship to the country. Many modern studies, including those found on sagepub.com and ecommons.cornell.edu, point out that Gebre-Hiwot saw the risks of state decay, persistent poverty, and lack of critical infrastructure if Ethiopia failed to adopt rational administration and just social reforms. He admired Japan’s rapid modernization but warned that Ethiopia’s elite were clinging to old privileges and not preparing for a changing world.

His message was clear: modernization was urgent, but must come with justice and good government, not just imitation of Europe. Sadly, Ethiopia did not heed his advice quickly enough. Later decades would see social upheaval, economic troubles, and even more bitter struggles over reform versus tradition. In this sense, Gebre-Hiwot Baykedagn stands as not only a founding intellectual but as a prophet whose warnings still echo in Ethiopia’s ongoing journey for development and unity.

Gebre-Hiwot’s story is a call to remember that nations rarely get a second chance to listen to their visionaries.