Devaluation and Ethiopia’s balance of payments

By Worku Aberra

August 3, 2024

In the previous installment, I demonstrated how devaluation of the Birr through the adoption of a floating exchange rate fuels inflation in Ethiopia. Beyond the variables discussed in Part I, speculation by merchants also contributes to rising inflation. If merchants hoard goods expecting future price increases, the resulting short-term decrease in supply drives up prices. Another factor that can raise prices is the market power of major wholesalers and distributors. If they have sufficient market power, they can increase the prices of goods far beyond what is justified by the devaluation of the Birr.

In this installment, I will examine how the devaluation of the Birr worsens Ethiopia’s chronic balance of payments in the short and immediate term.

The NBE argues that devaluation will “…significantly raise exports, FDI, and the country’s foreign exchange reserves.” Each of these claims needs to be examined closely. Let’s start with the impact of devaluation on exports and export earnings. When a currency is devalued, a country’s exports become cheaper in foreign currencies, potentially increasing the volume of exports and generating more export earnings. This increase in export earnings should theoretically improve the country’s balance of payments. However, empirically, the situation is more complex than what this simple analysis suggests.

The impact of devaluation on the total value of export earnings depends on the product’s price elasticity of demand, which measures the percentage change in the quantity demanded for a given percentage change in price. Demand for a product or service is considered price elastic when a given percentage change in price leads to a higher percentage change in the quantity demanded.

For example, if the price of a product decreases by a certain percentage and the quantity demanded increases by more than that percentage, the total revenue from selling the product increases. When the NBE argues that a decrease in the exchange rate, which reduces the price of Ethiopia’s exports in foreign currency, will increase export earnings, it assumes that the demand for Ethiopia’s export commodities is price elastic. This assumption implies that if the price of coffee, for instance, decreases by 30% in US dollars, the quantity demanded will increase by more than 30%, thereby boosting Ethiopia’s foreign exchange earnings from coffee sales.

The problem with this analysis is that it is inconsistent with the reality of Ethiopia’s export commodities. Ethiopia exports mostly agricultural products, whose demand is price inelastic. For example, empirical research shows that the price elasticity of coffee is 0.3, indicating coffee, which accounts for the largest share of Ethiopia’s exports, is price inelastic. If the price of coffee decreases by 30%, the quantity demanded of coffee increases by only 9%, reducing Ethiopia’s export earnings. Consequently, due to the devaluation of the Birr, it is likely that Ethiopia’s export earnings from coffee will decrease rather than increase. This conclusion is supported by empirical research. A group of researchers at Jimma University has shown that the devaluation of the Birr between 1987 and 2020 resulted in a decrease in the export earnings of coffee and khat.

At the same time, the devaluation of the Birr increases the price of imports in Birr. To assess the impact of the devaluation on import expenditures, we need to examine the price elasticity of Ethiopia’s imports. Most of the products that Ethiopia imports, such as oil, machinery, capital goods, and pharmaceuticals, tend to be price inelastic. When the price of a product that is price inelastic increases, the total amount of money spent on that product also increases. Therefore, due to Birr devaluation, Ethiopia’s expenditures on imports will rise. The decrease in export earnings combined with the increase in the import expenditures will worsen Ethiopia’s balance of payments. Instead of improving Ethiopia’s balance of payments deficit, as the NBE contends, the devaluation of the Birr will likely exacerbate it.

If the devaluation of the Birr likely decreases Ethiopia’s export earnings from the export agricultural products due to their price inelastic demand, what can be said about Ethiopia’s export of manufactured goods? Assuming the demand for manufactured goods is price elastic, as is often the case, the decrease in the price of these exports should increase Ethiopia’s foreign exchange earnings.

However, it was pointed out in the previous installment that the manufacturing sector in Ethiopia is highly import-dependent. This means that although the devaluation of the Birr will make the export of manufactured products cheaper, the increase in the price of imported inputs used to produce them will raise their prices. To assess the net effect of currency devaluation and the increase in input prices on the final price of exported manufactured goods requires empirical work. We are unable to undertake such an analysis. At this stage, we can say that the impact of devaluation on the price of Ethiopia’s manufactured exports is uncertain, but we can confidently conclude that the devaluation of the Birr will most likely worsen Ethiopia’s merchandise balance of trade.

Regarding the distributional effects of the devaluation, the NBE claims that “…millions of farmers involved in the production of exportable crops (coffee, sesame, pulses, flowers, fruits, vegetables, chat)…” will benefit from the devalued Birr. However, there are several problems with this assertion. First, because the demand for most of these agricultural products is price inelastic, export earnings will decrease, not increase, as I have demonstrated earlier. Second, the proportion of the revenue that farmers receive from agricultural exports is low. It is estimated that coffee farmers receive between 50% and 60% of the FOB price but only 1— 3 % of the retail price of a cup of coffee sold in cafes in Europe or North America and 2—6%.

The NBE also argues that the devaluation of the Birr will attract foreign direct investment because it would be cheaper for foreigners to invest in Ethiopia. While the devaluation of the Birr may initially make it cheaper for foreigners to invest in Ethiopia, investors consider variables beyond the exchange rate when making long-term investment decisions. One key variable that they consider is a country’s political stability. If a country is politically unstable, investors are likely to refrain from investing, regardless of the value of the currency. Given the political problems Ethiopia faces today, including armed insurrections in Oromia and the Amhara region, it is very unlikely that the devaluation of the Birr will attract foreign direct investment.

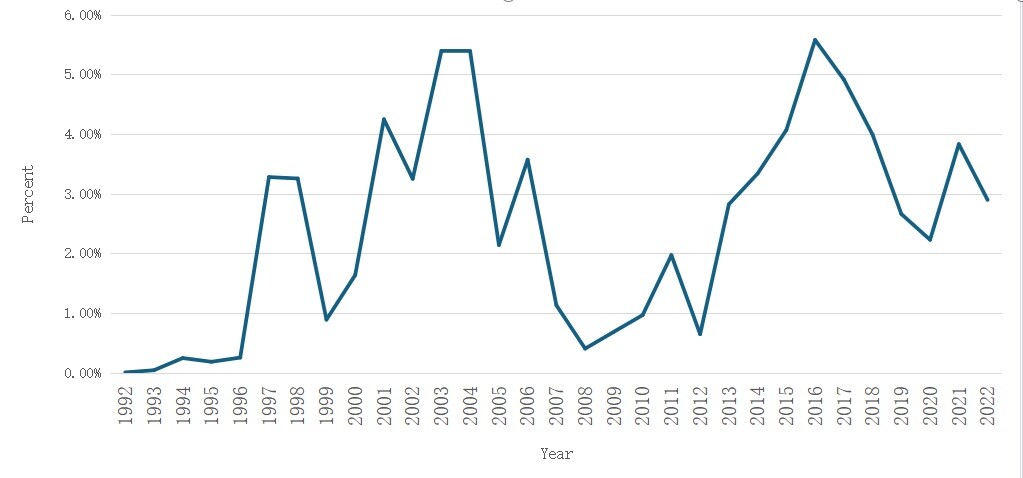

World Bank data on FDI shows that it is highly sensitive to the political environment in Ethiopia. Figure I below illustrates FDI as a percentage of GDP from 1993 to 2022.

Figure I

Foreign direct investment as percentage of GDP

(1993—2022)

Source: World Bank, Development Indicators.

As shown above, FDI is highly volatile and sensitive to political developments in Ethiopia. The low points of FDI correspond to major political events. During the Ethio-Eritrea war, FDI decreased from 3.25% of GDP to 0.98% between 1997 and 1999. Following the disputed 2005 election, the share of FDI out of GDP dropped from 5.38% in 2004 to 0.40% in 2008. During the uprising against the TPLF in 2015, FDI fell from 5.58% in 2015 to 4% in 2018, and it declined further to 3.83% after Abiy Ahmed’s ascendance in 2019. Its share has continued to decrease in recent years to 2.89% in 2023. Therefore, as long as there is political instability, no degree of devaluation will attract foreign investment to Ethiopia

Another contributing factor that affects the decision of foreign investors is currency stability. While devaluation makes it cheaper for foreigners to invest in a country, the macroeconomic conditions in Ethiopia suggest that the Birr will likely continue to lose value in the short and long term. The continued devaluation of the Birr will undermine investor confidence and discourage investment in Ethiopia. As the value of the Birr depreciates, the amount of money that foreigners can repatriate in foreign currency will decrease. Therefore, given the current political instability and the potential volatility of the Birr, the impact of devaluation on foreign direct investment is unclear, particularly considering the current level of political instability in Ethiopia

An important source of foreign exchange for Ethiopia has been remittances from the Ethiopian diaspora. The NBE asserts that, because of the new exchange rate regime, the difference between the parallel rate of exchange and the market-determined rate of exchange will diminish, and the diaspora will likely use official channels to send money to Ethiopia. However, this assertion ignores the political considerations of the diaspora when sending money to Ethiopia. Due to the repressive measures taken by the government, many members of the Ethiopian diaspora community have boycotted official channels and will likely continue to do so as long as political repression persists in Ethiopia.

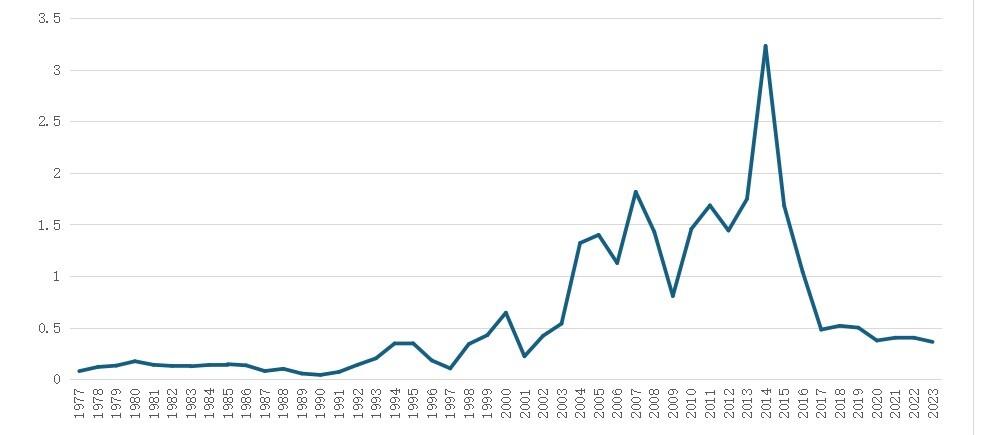

I have collected data on remittances from the World Bank and presented it in Figure II below.

Figure II

Remittances as a percentage of GDP

(1977—2023)

Source: World Bank, Development Indicators

Historical data from the World Bank shows that, in general, remittances from the Ethiopian diaspora have increased, with short-term fluctuations reflecting external economic conditions. Recessions in the West, such as those in 2001, 2007-2008, and 2020, have resulted in lower remittances to Ethiopia. Further, political instability in Ethiopia has also affected remittances through official channels.

Remittances reached their highest level in 2014, accounting for 3.23% of GDP, but they have been declining steadily with the deteriorating political situation in Ethiopia. In 2023, remittances accounted for only 0.36% of GDP. Since political factors play a significant role in the diaspora’s decision to send money to Ethiopia, especially through official channels, and since the gap between the market-determined exchange rate and the parallel exchange rate will likely remain high, remittances cannot be considered a stable source of foreign exchange for Ethiopia.

One significant effect of the devaluation of the Birr, acknowledged even by the IMF and the World Bank, is its negative impact on the value of Ethiopia’s foreign debt and interest payments. When the Birr lost 30% of its value on July 29, the country’s foreign debt and interest payments increased by an equivalent amount in a single day. As the devaluation of the Birr continues, as is expected, the burden of Ethiopia’s foreign debt, denominated in foreign currencies, will rise sharply when converted back to Birr. This also means that the interest payments on this debt will escalate correspondingly. The increased interest payments will intensify Ethiopia’s demand for foreign exchange, thereby exacerbating the country’s balance of payments issues. The growing debt servicing costs will further strain Ethiopia’s limited foreign exchange reserves, making it more challenging to manage its external financial obligations and contributing to the worsening of the balance of payments deficit.

The NBE’s claim that Ethiopia’s foreign exchange reserves will increase because of devaluation is questionable given the projected decrease in export earnings, the certain rise in import expenditures and interest payments on foreign debt, the anticipated decline in FDI due to political and economic instability, and the reluctance of the diaspora to use official channels to send money to Ethiopia.

The devaluation of the Birr and the adoption of a floating exchange rate are unlikely to improve Ethiopia’s chronic balance of payments deficit or raise the country’s foreign exchange reserves; in fact, they will likely worsen these problems. To mitigate its chronic foreign exchange shortages, Ethiopia will need to seek assistance from foreign governments, the IMF, and the World Bank.

Worku Aberra is a professor economics at Dawson College, Montreal, Canada.