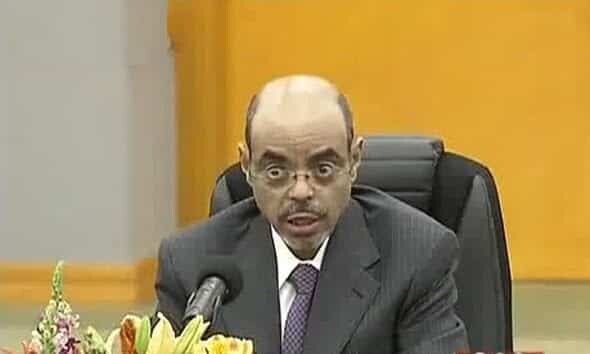

The passing of Meles Zenawi marked the end of an era — not just in governance, but in the symbolic legacy of Ethiopian revolutionaries. His funeral, held with considerable ceremony at Holy Trinity Cathedral, raised eyebrows for its rich symbolism. Traditionally, this cemetery was the resting place of imperial aristocracy — the very class that student revolutionaries of the 1960s and 70s considered their ideological nemesis. It was here that Emperor Haile Selassie was reburied after his body, once discarded ignominiously under Mengistu’s regime, was restored to honor. Yet now, a man who led a Marxist insurgency is buried beside monarchs.

The passing of Meles Zenawi marked the end of an era — not just in governance, but in the symbolic legacy of Ethiopian revolutionaries. His funeral, held with considerable ceremony at Holy Trinity Cathedral, raised eyebrows for its rich symbolism. Traditionally, this cemetery was the resting place of imperial aristocracy — the very class that student revolutionaries of the 1960s and 70s considered their ideological nemesis. It was here that Emperor Haile Selassie was reburied after his body, once discarded ignominiously under Mengistu’s regime, was restored to honor. Yet now, a man who led a Marxist insurgency is buried beside monarchs.

Critics — ranging from exiled revolutionaries to Eritrean nationalists — question this choice. Some argue Meles should have been buried in Adwa, his place of birth, or Dedebit, the birthplace of his rebellion. But these debates obscure a deeper tension: was the revolution ever truly about liberation? Or was it a cycle of elite competition masked in ideological garb?

The Legacy of Post-Liberation Statesmanship

Meles’s rule, spanning two decades, was characterized by a shift toward pragmatism — at least compared to some of the more dogmatic factions of the TPLF. He tried to steer Ethiopia away from the rigid ideologies of its guerrilla past. The shared burial ground, symbolic as it is, may represent an attempt to tone down the revolutionary rhetoric. But can post-rebellion statesmanship alone undo the legacy of fifty years of violent political struggle?

Ethiopia’s modern political history remains marred by authoritarianism, factionalism, and power monopolization. Despite Meles’s economic record — often praised in Western circles — Ethiopia lacks the foundations of a liberal political system. And the prospects for inclusive governance, peaceful power transitions, and pluralism remain uncertain.

The Revolutionary Burden

The student radicals who spearheaded Ethiopia’s political upheaval in the 1970s embraced revolution as salvation. Yet half a century later, the country remains trapped in cycles of instability. Was it worth the bloodshed, economic dislocation, and international isolation?

Some commentators now focus only on the Meles regime’s economic gains, downplaying the democratic deficit. But this selective memory ignores a critical counterfactual: had Ethiopia developed stable political institutions and allowed peaceful transfers of power, it might have achieved similar — or even superior — economic progress without the cost in human lives and opportunities.

Compare this with South Korea or the Southeast Asian Tigers: these nations moved from agrarian poverty to industrial prosperity in just a few decades. They used Western aid and technology after WWII to build infrastructure, strengthen education, and industrialize. Meanwhile, Horn of Africa revolutionaries were busy glorifying their years in the bush. They paraded tractors like trophies — machines often imported from countries like South Korea and China, whose development trajectory they ignored.

The Ghosts of Marxism

Eritrea’s regime, for example, still touts its “self-sufficiency,” showcasing roads and farms built with what amounts to forced labor. Ethiopia under Meles clung to Marxist ideals well into the 1990s, even as the Soviet Union collapsed. This ideological inertia reflected a broader unwillingness to reimagine political and economic models outside of dated dogma.

Ironically, the Derg — the Marxist junta Meles fought against — was itself built on the same ideology. Both rebel and regime were mirror images in many respects, products of the same radical intellectual culture. Statues of peasants and proletarian heroes still stand on Churchill Avenue in Addis Ababa, a relic of this ideological echo chamber.

Christopher Clapham called it Ethiopia’s “politics of emulation” — a cycle of borrowing foreign models and applying them out of context. The revolutionary civil wars that followed were less about ideology and more about regional rivalry, particularly in the northern highlands. The real revolution — one involving the long-exploited southern peoples — never fully materialized.

A Revolution That Never Was

Clapham later regretted using the term “revolution” to describe Ethiopia’s civil war. In reality, it was a regional rebellion driven by elite northern factions who had lost favor under the imperial system. The marginalized peoples of southern Ethiopia, long subjected to serfdom and neglect, played only a peripheral role in the uprisings that toppled the Derg.

This undermines the romanticized narrative of a popular revolution. The civil war was a war among elites — northern groups vying for control of the state, not a nationwide upheaval. Yet even today, many in the diaspora who once embraced the revolutionary cause continue to rehash old slogans and grievances. The language of betrayal — “the revolution was hijacked” — persists on all sides.

The Vicious Circle

In Why Nations Fail, Acemoglu and Robinson describe a “vicious circle” in which political conflict and extractive institutions feed each other. Ethiopia fits this model well. The revolutionary road promised progress but delivered paralysis. Liberal politics were never well understood — or deliberately rejected — by both the imperial court and the radical student class.

And yet, Meles and his contemporaries were hailed in the West as “Renaissance leaders.” In truth, they were military rulers presiding over famished populations — farmers coerced into housing and feeding guerrilla armies for decades. Ethiopian peasants were not the beneficiaries of war, but its most enduring victims. Forced displacements, famine, and mass exoduses defined their experience.

In Eritrea, the legacy is even starker. Its authoritarian regime remains one of the most repressive in the world. The populace, drained and demoralized, poses little internal challenge to power. The revolution consumed its own children, and left little hope in its wake.

Lessons from the Mountains

A British officer in the 1968 expedition remarked on Ethiopia’s formidable landscape — steep escarpments and treacherous terrain. These mountains are now metaphors for the political struggle itself: relentless climbs with no visible summit. Author Moses Isegawa used them in Abyssinian Chronicles to symbolize Uganda’s political instability. The metaphor fits Ethiopia just as well.

Thailand, often cited as a peer civilization by development historians, followed a very different path. Its monarchy and elites weathered student protests, coups, and even communist insurgency, without allowing armed rebellion to become the norm. Corruption existed, but a political culture emerged that prioritized national development over ideological war. Thailand’s technocrats and institutions, while imperfect, allowed for growth and relatively smooth transitions.

The Way Forward: Institutions, Not Men

Ethiopia today teeters between the past and the possible. Its political fate cannot hinge on personalities, however powerful. Meles was sometimes described as an “institution unto himself,” but that’s precisely the problem. States need real institutions: independent judiciaries, electoral commissions, civilian control of the military, a free press — mechanisms that survive any one man’s death.

If Ethiopia is to escape the revolutionary dead-end, it must abandon the romance of armed struggle and invest in building liberal democratic foundations. Political power must devolve to the people, and inclusive, peaceful governance must become the norm.