It is astonishing to recall that having a television satellite dish was a criminal act in Ethiopia 15 years before. Ironically, even low-cost houses built by the government, dubbed condominiums, are now swarmed by the devices.

Similarly, people used to be jailed for bringing in credit cards to the country, which now have become a popular instrument of financial transaction, promoted by both private and governmental banks.

Both examples show the distrust that the Ethiopian state has always had towards technological advancement. There seems to be an inherent interest to put every beast under control; no matter how harmless it is.

A similar move is happening with a new piece of legislation being introduced to limit a rather transformative wave of telecommunications technology.

No better competing force of transformation can be found in the post-1991 economy of Ethiopia than the expansion in telecommunications service provision. Beeping mobile phones, flourishing Internet cafes, and wired youths are typical features of the emerging nation that the Revolutionary Democrats have orchestrated through their developmental state model. It, indeed, has paid them back in dividends.

The relationship between people and their mobile phones has grown too big to ignore. Such is also the case with people and their accounts on different websites, not to mention social networking sites. So complicated has the relationships become that regulation is getting tricky.

It is with the intention of controlling the intensifying risk factor accompanying the infrastructure expansion that a bill on controlling telecommunications crime was tabled to the Ethiopian Parliament, last week. Titled, Telecom Crime Controlling Prevention Proclamation, the bill provides a legal framework to manage crimes on and through telecommunications systems. The mounting intricacy of the crime, with its effects going beyond economic costs, initiated the drafting, reads the preamble of the bill. Having a legal framework that effectively punishes criminals is essential to curtail the cost burden on the national economy, the argument goes.

There is no denying fact that telecommunications networks have increasingly become hotspots for international criminals. It is increasingly putting the safety and security of individuals, enterprises, and nations in danger. Controlling such crime is, indeed, in the interest of societal normalcy. Where the debate lies is on how to do it.

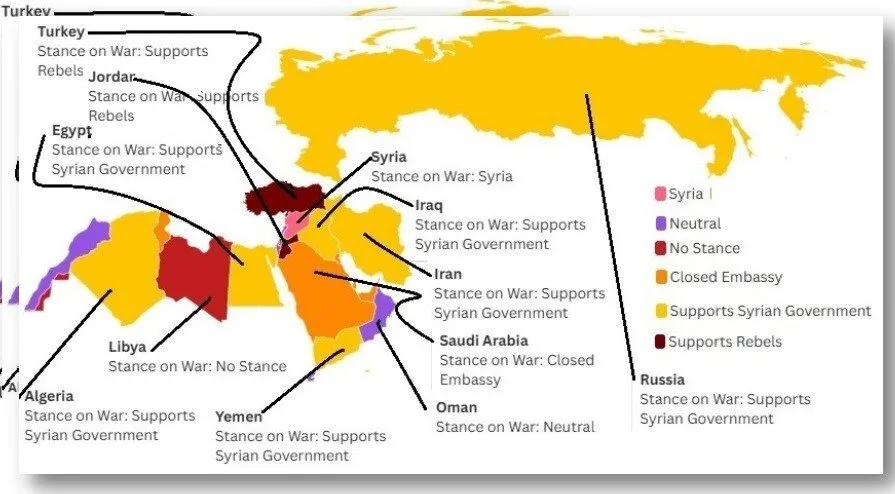

A global movement to provide states with more control over telecommunications systems including Internet is gaining momentum in recent years with hegemonic states such as China and Russia standing at the fore. From elementary concepts such as the right to anonymity and privacy to complex issues of data storage security, the movement envisions giving the state overwhelming control over communications through international telecommunications networks.

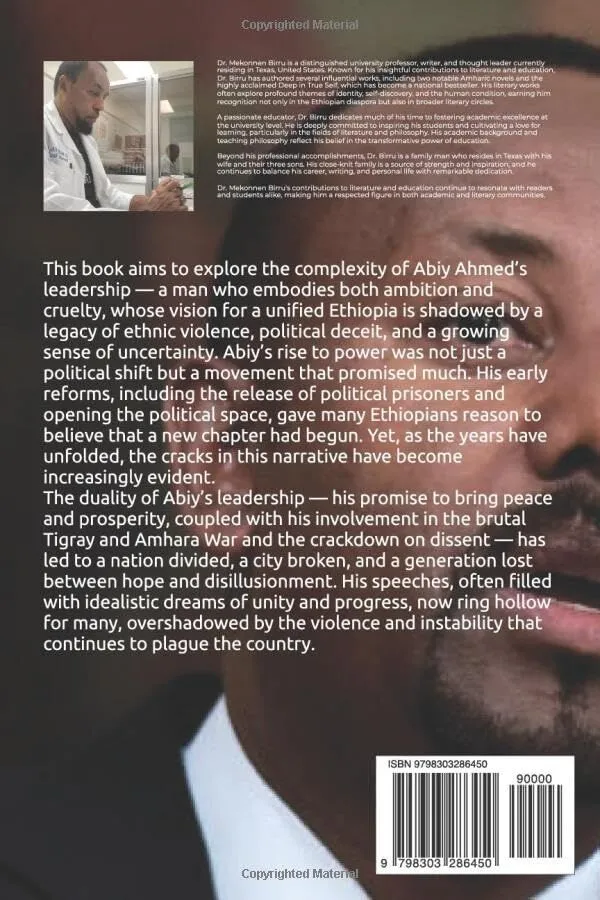

The new bill drafted by the EPRDFites seemingly copies that intent but in the very harshest way. It puts rather horrendous punishments on acts that could not compellingly be put into the category of national risks. It overstretches the concept of national security at the expense of individual liberty, a recent trend in Ethiopian legislative history.

Protecting national interests including security and stability are mentioned as the prime objectives of the bill. That would have been a good excuse for the drafters had the Ethiopian Constitution not put it under an exception to the inviolable rights of individual privacy.

By and large, the bill puts all technological advancements in the world, except those known to the executive branch of the government, under the category of the social bad. Possessing them is declared criminal and so is using them.

The complexity of the telecommunications sector is beyond the reach of regulation, the bill self-evidently shows. It is obviously a swift current that no one can effectively tame. Controlling such a tide through legislating will obviously prove futile, all available global evidence shows.

Sadly, though, the Revolutionary Democrats have opted to criminalise people for knowing more than they do. By way of putting an unspeakable punishment on inherent human curiosity, they deposit an unrestrained power to define the demand for information and knowledge under their disposal. It is, indeed, worrying.

As the Ethiopian Constitution rightly puts it, individuals have inviolable rights of privacy and expression. There shall be no limitation on the medium of experiencing these rights.

Public officials are obliged with the responsibility of respecting these rights, if not under exceptional cases. Those exceptions that are related to national security, as are rightly stated in the supreme law of the land, have to be underpinned with compelling evidence.

In contrast, the new bill makes the acts of possessing communications software and hardware, beyond those to be listed by the executive, as criminal. It contradicts the Constitution, for it categorically puts a broader cap on the media of communication that cannot be compelling in view of the law.

Article 10, Sub-article 2 of the bill, for example, sets the maximum punishment for those individuals found providing voice over Internet protocol (VoIP) services and those who use these services, if intentionally, at eight years with fines amounting to five times the gained benefit and, if through negligence, two years with a 20,000 Br fine, respectively.

Eventually, through these provisions, the use of popular technological products that facilitate long-distance communications such as Viber and Skype software will be criminalised. Possessing this software and making use of it will become grossly punishable.

Worse, the bill transcends the Constitution by violating the right to individual privacy with a long list of admissible evidence. Although individual notes and communications are protected by the Constitution, the new bill makes digital evidence collected through unlawful interference admissible in a court of law.

No matter how infant the debate over privacy is, closer, there is no worse situation than providing the state with the power to interfere with individual communications. At best, it is surrendering individual liberty to the illegitimate operations of the state, which, normally, should have been obliged to protect them.

All of these provisions would have had less of an impact had the legislative body of the nation allowed enough space for objective deliberation. Laws dealing with communications and privacy are always debatable, even in the most monotonous political environments.

Sorrowfully, though, 99.8pc of the parliamentary seats are occupied with the ruling party. This provides it with a sweeping power to legislate its intent, as recent experiences show. No different is the case for the new telecom crime bill.

Poorly developed law enforcement and judicial institutions that eventually have limited knowledge about the nitty-gritty of technology will make the criminalisation even worse. There will be little chance to have a detailed technological debate in the court of law, as the expertise to adjudicate such disagreements is severely limited, if not nonexistent.

Curtailed through the new bill is the innovative capacity of citizens, which is highly sought-after in aspiring economies such as Ethiopia. As technology reduces the cost for innovation, economies looking for better competitiveness must strive for more of it.

State-sponsored declarations of suspicion such as the new telecom crime bill will have a huge impact on innovation, and, hence, competitiveness. Moreover, individual liberty, the basis of innovation, will severely be strained under the new bill.

At stake is the social and economic stability of the nation, at large. It is unimaginable to build a stable socio-political regime with individuals whose rights of privacy and expression are limited by law. The risk is indeed high for a multicultural nation.

A better future is still within reach of the EPRDFites, for they still have the space to review the draft law in line with global experiences. If, at all, their legislative intent is to fight cyber crime, they ought to recall that no better partner could be found in such a fight than liberated individuals. As much as they preach constitutionalism, they have to embrace the values that the Constitution clearly states.