By PAUL DELKASO

President Trump’s tweets—polarizing though they may be—carry hard realities beneath the rhetoric. His latest remark about the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), while framed with trademark bravado, deserves a closer look. Yes, his phrasing lacked nuance. But it wasn’t without a kernel of truth.

The United States—through agencies like USTDA—did support Ethiopia’s energy infrastructure, conducting feasibility studies and advising power sector modernization (ustda.gov). USAID, under Power Africa, deployed technical experts and de-risking instruments to attract independent power producers across Ethiopia, from wind to geothermal. While this support didn’t finance GERD directly, it strengthened Ethiopia’s energy capacity—helping pave the road that GERD now dominates. And geopolitically? Trump did what many won’t admit: he escalated diplomatic pressure with Egypt and Ethiopia at a moment when miscalculation could’ve sparked regional war. His administration brought parties to Washington. He didn’t craft poetry—he forced conversations. His methods were abrasive, yes. But they altered trajectories. This isn’t new. Trump’s diplomacy—whether with Serbia-Kosovo, India-Pakistan, Israel-UAE, or even Rwanda-DRC—follows a pattern: blunt intervention, unpredictable style, consequential results.

As for the Nobel Peace Prize that never came? That’s Oslo’s call. But history doesn’t hand out awards—it records outcomes.

So let’s be honest: you can criticize the man—but denying his impact on peace negotiations is intellectually dishonest. Sometimes, it’s the unlikeliest voices that keep history from breaking.

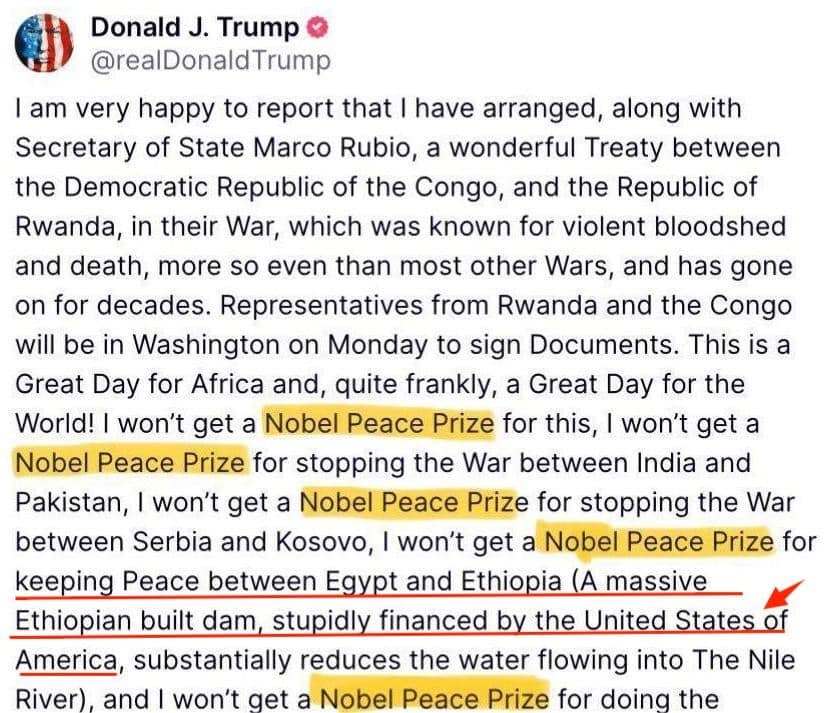

“I won’t get a Nobel Peace Prize for this, I won’t get a Nobel Peace Prize for stopping the War between India and Pakistan, I won’t get a Nobel Peace Prize for stopping the War between Serbia and Kosovo, I won’t get a Nobel Peace Prize for keeping Peace between Egypt and Ethiopia (A massive Ethiopian built dam, stupidly financed by the United States of America, substantially reduces the water flowing into The Nile River), and I won’t get a Nobel Peace Prize for doing the Abraham Accords in the Middle East… No, I won’t get a Nobel Peace Prize no matter what I do… but the people know, and that’s all that matters to me!” — President Donald J. Trump, June 20, 2025

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) has been financed overwhelmingly by Ethiopia itself, with no evidence of direct U.S. funding for its construction. Ethiopia raised money through government bonds, domestic revenues, and diaspora contributions, while international financiers largely stayed away due to the project’s controversy. Even indirect U.S. financial support appears minimal – in fact, the U.S. withheld certain aid to Ethiopia during the height of the GERD dispute rather than funding the dam. American involvement has primarily been diplomatic and strategic. The U.S. Treasury and State Department facilitated talks between Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan from 2019–2020 to broker an agreement on filling and operating the dam. The Trump administration even cut about $100 million in aid to pressure Ethiopia amid the stalemate, a move perceived as siding with Egypt. This stance was later softened by the Biden administration, which de-linked U.S. assistance from the dam negotiations.

Historically, U.S. government agencies and intelligence have monitored Nile water developments closely. A declassified CIA analysis from 1986 warned that large upstream dams in Ethiopia could be “of grave concern” to Egypt and might lead to conflict. The same report judged that while an Egyptian airstrike on an Ethiopian dam was unlikely, Cairo might covertly support rebels to stall Ethiopia’s project – highlighting how strategically sensitive the GERD’s precursors were even decades ago. Overall, the United States’ motivations regarding GERD center on preventing regional instability and balancing ties with both Egypt and Ethiopia. Washington views Egypt’s Nile water security as an existential issue for a key ally, even as it acknowledges Ethiopia’s right to develop resources for much-needed electricity. This report details the evidence (or lack thereof) of U.S. financial support, the diplomatic role played by the U.S., and the geopolitical context shaping American policy on the GERD.

__________________________________________________________

United States Involvement in Ethiopia’s Grand Renaissance Dam: Funding and Geopolitics-Context

Summary of Findings

Article content

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) has been financed overwhelmingly by Ethiopia itself, with no evidence of direct U.S. funding for its constructionjwafs.mit.edu. Ethiopia raised money through government bonds, domestic revenues, and diaspora contributions, while international financiers largely stayed away due to the project’s controversyjwafs.mit.edu. Even indirect U.S. financial support appears minimal – in fact, the U.S. withheld certain aid to Ethiopia during the height of the GERD dispute rather than funding the damreuters.com. American involvement has primarily been diplomatic and strategic. The U.S. Treasury and State Department facilitated talks between Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan from 2019–2020 to broker an agreement on filling and operating the damhome.treasury.gov. The Trump administration even cut about $100 million in aid to pressure Ethiopia amid the stalematereuters.com, a move perceived as siding with Egypt. This stance was later softened by the Biden administration, which de-linked U.S. assistance from the dam negotiationssecurityincontext.com.

Historically, U.S. government agencies and intelligence have monitored Nile water developments closely. A declassified CIA analysis from 1986 warned that large upstream dams in Ethiopia could be “of grave concern” to Egypt and might lead to conflictcia.gov. The same report judged that while an Egyptian airstrike on an Ethiopian dam was unlikely, Cairo might covertly support rebels to stall Ethiopia’s project – highlighting how strategically sensitive the GERD’s precursors were even decades agocia.gov. Overall, the United States’ motivations regarding GERD center on preventing regional instability and balancing ties with both Egypt and Ethiopia. Washington views Egypt’s Nile water security as an existential issue for a key ally, even as it acknowledges Ethiopia’s right to develop resources for much-needed electricity. This report details the evidence (or lack thereof) of U.S. financial support, the diplomatic role played by the U.S., and the geopolitical context shaping American policy on the GERD.

Overview of the GERD Project and Its Financing

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam is a massive hydropower project on the Blue Nile in Ethiopia’s Benishangul-Gumuz region, under construction since 2011 and nearing completion. With a planned installed capacity of over 5,000 MW, GERD will be Africa’s largest hydroelectric damen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. From the outset, Ethiopia opted to self-finance the $4–5 billion project after international lenders hesitated. The dam’s construction has been funded by Ethiopian government bonds and private donations, including contributions from ordinary citizens and the diasporaen.wikipedia.org. By 2017, Ethiopia had mobilized billions of birr through local bond sales and fundraising rallies, reflecting a sense of national pride and sovereignty around the project. External financing was scarce: as one expert study noted, “Ethiopia is financing the construction of the GERD without international funds. The Ethiopian people are thus making substantial sacrifices to implement this project from domestic financing.”jwafs.mit.edu In other words, no major Western aid, multilateral development bank loan, or U.S. grant has gone toward building the GERD.

The reluctance of traditional donors stems from the dam’s transboundary impacts. Egypt vocally opposed GERD from the start as a potential threat to its downstream water supply, and Sudan had its own concerns. Global financial institutions (e.g. the World Bank) and Western governments were unwilling to fund GERD without a regional agreement, to avoid entanglement in a Nile water dispute. This left Ethiopia to shoulder the costs. The country’s strategy succeeded in maintaining full ownership and control, but at the price of straining its finances. Notably, Ethiopia did secure some outside help for related infrastructure: for example, Chinese state banks extended about $3 billion in loans since 2013 to build power transmission lines and electrical equipment for GERDsecurityincontext.combrookings.edu. The dam’s main civil construction was contracted to Italy’s Salini Impregilo (Webuild), and later Chinese contractors were hired for parts of the electro-mechanical workssecurityincontext.com. These were business deals and export credits, however – not direct aid. Other Gulf states showed interest in Ethiopia’s energy sector, but no direct Gulf or U.S. financing of the GERD’s construction has been documented. In fact, Egypt actively lobbied foreign governments (including U.S. allies in the Middle East) not to support the projecten.wikipedia.org. Consequently, GERD stands as a domestically funded project, a point of national pride for Ethiopians and a deliberate choice to avoid external conditionalities.

U.S. Financial Support: Fact vs. Fiction

Amid this financing landscape, the question arises whether the United States ever covertly or indirectly funded GERD or its ancillary works. Based on available evidence, the answer is no. The U.S. government has not provided any direct financial support for GERD’s construction. No U.S. development agency (USAID, Millennium Challenge Corporation, etc.) has had a program to build the dam. GERD is absent from U.S. aid budgets and congressional appropriations. This was recently highlighted when former President Donald Trump made a claim during a 2024 campaign speech that “the United States stupidly funded the Ethiopian dam.” Ethiopian and independent observers immediately refuted this assertion, noting that “Trump’s claim that the United States ‘financed’ the project does not seem to have any evidence”reddit.com. All credible accounts show Ethiopian taxpayers and bond-buyers virtually financed the entirety of GERD, not American taxpayersreddit.com. In reality, the U.S. role has leaned more toward withholding or redirecting funds in response to the dam dispute, rather than contributing funds to the dam.

During the Trump administration, as negotiations between Egypt and Ethiopia faltered, Washington actually froze or cut certain aid to Ethiopia as leverage. In August 2020, the U.S. State Department, with White House approval, decided to suspend up to $100 million in bilateral assistance, explicitly linking the freeze to Ethiopia’s stance on the GERD talkssecurityincontext.comreuters.com. Much of this affected aid was in security and development programs (e.g. military cooperation, agricultural and border projects) that were unrelated to the dam, but the message was clear: the U.S. was willing to use aid as a stick to push Ethiopia toward a compromisesecurityincontext.comreuters.com. This unprecedented step underscores that the U.S. was not financially supporting GERD – rather, it was ready to penalize Ethiopia by withholding aid. Ethiopian officials and public were dismayed; many saw it as undue pressure in favor of Egypt. Indeed, after Ethiopia began filling the dam’s reservoir unilaterally in 2020, U.S. statements grew sharper. President Trump, on a call with Sudan’s and Israel’s leaders, mused that Egypt might “end up blowing up that dam,” calling Ethiopia’s actions unacceptablesecurityincontext.com. Such remarks, alongside the aid freeze, were interpreted in Addis Ababa as Washington taking Egypt’s sidesecurityincontext.com.

By early 2021, the incoming Biden administration reviewed this approach. U.S. officials reversed the aid suspension policy, announcing they would “de-link” assistance to Ethiopia from the GERD issuesecurityincontext.com. This meant Ethiopia’s receipt of U.S. aid (which is largely humanitarian and health-related) would no longer be conditional on dam negotiations – a tacit acknowledgment that politicizing aid had backfired. However, even under Biden, the U.S. did not offer any positive financial incentives for GERD. Instead, it continued to urge a negotiated solution and offered technical help through observation missions. In summary, no evidence has surfaced of the CIA, USAID, or any U.S. entity covertly funneling money into GERD’s construction. On the contrary, the U.S. record is one of financial abstention (letting Ethiopia self-finance) coupled with financial coercion (temporarily halting other aid to press for a deal).

It is worth noting one historical U.S. contribution: the dam’s very site was originally identified by American engineers decades ago. From 1956–1964, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation conducted a Blue Nile hydrological survey in Ethiopia, which first pinpointed the location near Guba as ideal for a large damen.wikipedia.org. Those Cold War-era plans were shelved due to political upheaval in Ethiopia, but Addis Ababa resurrected the concept in 2010. While this early technical study was U.S.-funded, it was purely exploratory. There is no indication of U.S. funding in the dam’s modern incarnation beyond that long-ago survey. In fact, Ethiopia deliberately kept GERD financing domestic to avoid foreign vetoes – a response to history, since Egypt had previously used its influence to block World Bank or U.S. funding for upstream projectsbrookings.edu. Thus, claims of hidden U.S. financing or CIA money behind GERD are not supported by the factual record.

U.S. Diplomatic Role and Mediation Efforts

Where the United States has been deeply involved is in diplomacy surrounding GERD, especially as the dispute intensified in the late 2010s. At Egypt’s urging, the U.S. stepped in to facilitate talks when African Union-led negotiations stalled. In November 2019, President Trump tasked the U.S. Treasury (then Secretary Steven Mnuchin) to observer and mediate discussions between Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan, in coordination with the World Banksecurityincontext.com. Over the next few months, multiple rounds of negotiations took place in Washington, D.C., and in the three countries’ capitals. This culminated in a draft agreement by February 2020 on guidelines for filling and operating the GERD, which the U.S. called balanced and technically soundhome.treasury.govhome.treasury.gov. The Treasury Department’s February 28, 2020 statement lauded Egypt for initialing the deal and urged Ethiopia to sign, explicitly warning that “final testing and filling should not take place without an agreement”home.treasury.gov. The U.S. cast this as implementing the 2015 Declaration of Principles (signed by the three countries) and emphasized equitable use and “no significant harm” to downstream nationshome.treasury.gov.

However, Ethiopia walked away from the U.S.-brokered draft, perceiving it as unfairly favorable to Egypt’s water quota demands. Ethiopian officials felt Washington had overstepped by issuing what seemed like an ultimatum. After Ethiopia skipped the final meeting in Feb 2020, the U.S. openly admonished Addis Ababa for proceeding with filling the dam. The withholding of $130 million in aid (as noted earlier) was part of this diplomatic pressuresecurityincontext.com. President Trump’s off-the-cuff remark about Egypt blowing up the dam (made in October 2020) further poisoned the atmospheresecurityincontext.com. Ethiopia accused the U.S. of diplomatic bias, and even lodged protests. From Ethiopia’s perspective, the U.S. had “picked a side” – undermining America’s traditional role as an honest broker in Nile issues. Egypt, on the other hand, welcomed U.S. engagement as leverage to secure a binding agreement.

After 2021, the U.S. recalibrated its approach. The Biden administration stated it “rejected the Trump Administration’s approach” and removed GERD-related conditions on aidsecurityincontext.com. U.S. diplomats still support a negotiated settlement but now mainly defer to the African Union-led process, with the U.S. and EU in observer roles rather than driving the talkssecurityincontext.comsecurityincontext.com. Special envoys and ambassadors have periodically visited Cairo, Khartoum, and Addis Ababa to encourage compromise. American officials emphasize that a win-win deal is possible – for instance, cooperative management of the dam could ensure Egypt’s water security during droughts while allowing Ethiopia to generate power. Think tanks have urged the U.S. to stay engaged to prevent the Nile dispute from escalating into conflictsecurityincontext.com. In practical terms, Washington has offered technical expertise (e.g. data sharing, dam safety know-how) and quiet diplomacy, but no direct financial sweeteners or investments to resolve the impasse. One indirect role the U.S. has played is through its influence at the World Bank and IMF: Ethiopia’s hopes of external financing for future Nile projects or regional power interconnections likely hinge on reaching an accord, and U.S. support (or lack thereof) in those institutions can affect Ethiopia’s access to credit. Overall, the U.S. sees its role as a mediator and stabilizer in the GERD saga, mindful of its strong relations with all parties – a role complicated by the need to reassure Egypt (a longstanding ally) while not alienating Ethiopia (a pivotal Horn of Africa partner).

Geopolitical Context: Egypt, Sudan, and U.S. Strategic Interests

The Nile River’s geopolitics form the backdrop for U.S. actions regarding the GERD. Egypt, which depends on the Nile for ~90% of its freshwater, has framed GERD as an “existential threat” if not managed properlybrookings.edu. Cairo points to its “historic rights” under the 1929 and 1959 Nile treaties (which granted Egypt the lion’s share of Nile waters and a veto on upstream projects)securityincontext.comsecurityincontext.com. Ethiopia, not a party to those colonial-era agreements, rejects them as obsolete, asserting its sovereign right to use the Blue Nile’s resources for developmentsecurityincontext.comsecurityincontext.com. This fundamental gap – Egypt’s water security versus Ethiopia’s development needs – has fueled a decade-long standoff. Sudan, caught in between upstream and downstream, has had a nuanced position. Initially, Sudan sided with Egypt’s concerns and worried about water flow and its own dam safety. But over time, Sudan began to see benefits in GERD (like more regulated flows reducing floods and offering cheap power). By the mid-2010s, Khartoum tilted toward support for GERD in principle, even as it sought guarantees on coordinationen.wikipedia.orgbrookings.edu. Sudan’s stance has fluctuated with its internal politics, but it often plays the role of mediator since it stands to gain some advantages from a well-managed GERD.

For the United States, these dynamics engage several strategic interests: regional stability, alliance obligations, and broader geopolitical competition. Egypt is one of the top recipients of U.S. military aid (about $1.3 billion annually) and a cornerstone of U.S. strategy in the Middle East/North Africa. A destabilizing water crisis in Egypt – or worse, war between Egypt and Ethiopia – would threaten U.S. interests. The CIA and other U.S. intelligence agencies have long monitored the potential for conflict over the Nile. A 1986 CIA report, for example, explicitly noted that “Ethiopian plans to build a series of dams on the Blue Nile are of grave concern to Egypt… Already frosty relations… may deteriorate to the point of conflict should Ethiopia initiate large-scale unilateral development projects on the Nile.”cia.gov. This warning proved prescient when Ethiopia launched GERD in 2011. The same declassified analysis observed that if diplomacy failed, Egypt might consider sabotage options – “supporting major dissident forces in northern Ethiopia in hopes… to preclude dam construction” – since a direct attack on the dam would be politically riskycia.gov. Such insights show that Washington views the Nile dispute as a flashpoint that could ignite broader instability or proxy conflicts in the Horn of Africa region. This concern is amplified by the fact that both Egypt and Ethiopia are significant U.S. partners: Egypt for regional security and peace with Israel; Ethiopia for peacekeeping, counter-terrorism in East Africa, and as Africa’s second most populous nation with growing influence.

U.S. strategic interest also lies in checking other great power involvement. China’s role in GERD (through financing and construction contracts) illustrates Beijing’s expanding footprint in African infrastructuresecurityincontext.com. While China officially stays neutral on the water rights issue, its financial support to Ethiopia indirectly bolsters Addis Ababa’s position. The U.S., wary of losing influence, has an interest in offering an alternative or at least ensuring China’s involvement doesn’t undercut Western leverage. Likewise, Gulf states (like the UAE, which has invested in Ethiopia and at times tried quiet mediation) and Russia (which has signaled support for Egypt’s stance in the UN) are actors the U.S. watches in this contextgulfif.orgsecurityincontext.com. The GERD dispute also ties into regional blocs: recently, both Egypt and Ethiopia joined the BRICS grouping (alongside China and Russia), potentially shifting alignments on the issuesecurityincontext.com. These developments add complexity to U.S. calculations.

At its core, the U.S. aims to prevent a “water war” over the Nile. American diplomats frequently cite that a cooperative agreement on GERD would unlock win-win opportunities – such as power trading, joint drought planning, and regional integration – whereas confrontation could be disastroushome.treasury.govsecurityincontext.com. Regional stability in the Nile Basin aligns with preventing humanitarian crises (massive disruptions to water or food in Egypt or Sudan could trigger refugee flows and conflict). It also aligns with U.S. priorities in Africa, which include supporting economic development and electricity access (GERD will significantly boost electricity for Ethiopia and neighbors) while avoiding zero-sum outcomes. In public, U.S. officials stress that they “do not take sides” on how water should be allocated, but rather insist on fair process and peaceful dialogue. Privately, the U.S. clearly recognizes Egypt’s existential angst – as one analyst put it, “For Egypt, the Nile is a national security issue; in 1979 President Sadat warned the only thing that could take Egypt to war again was water”securityincontext.comsecurityincontext.com. The U.S. therefore seeks to reassure Egypt (for example, by acknowledging its “water security” in statementssecurityincontext.com) even as it encourages Ethiopia’s legitimate development. Navigating this balance is challenging, and it explains why the U.S. has sometimes oscillated between carrot and stick with Ethiopia.

Intelligence and Declassified Insights

The mention of intelligence agencies in the GERD context often raises the question of whether entities like the CIA have been covertly involved in either supporting or sabotaging the dam. There is no public evidence that the CIA or any U.S. intelligence arm provided material support for GERD’s construction. Given the United States’ above-noted stance, such covert support would run counter to U.S. policy, which leaned toward cautioning Ethiopia (not enabling it). However, declassified CIA documents do shed light on U.S. strategic thinking regarding Nile waters and potential conflict. Aside from the 1986 CIA memorandum cited earlier, intelligence assessments through the years consistently flagged the Nile disputes as a source of tension: for instance, a 1970s CIA study on Egypt’s water outlook (later declassified) discussed Ethiopia’s nascent dam plans and Egypt’s dependence on upstream cooperationcia.gov. The CIA factored in scenarios such as droughts coinciding with GERD’s filling stage – which, if not managed cooperatively, could cause “disastrous consequences” for Egypt’s economy and food supply, potentially “lead[ing] to confrontation with upstream users”cia.gov. These analyses likely informed U.S. diplomatic contingency planning.

Another aspect is whether the U.S. might have played an intelligence-gathering role monitoring the GERD’s progress. It is known that the U.S. and Israel provided satellite imagery to Egypt in some instances to help gauge the dam’s reservoir levelsfacebook.com. Open-source satellite monitoring (e.g., NASA and commercial imagery) has indeed been crucial for all parties to track GERD’s filling. The U.S. has sophisticated technical means to observe such projects, and it is plausible that information was shared with allies (like Egypt) to increase transparency and avoid worst-case fears. This kind of behind-the-scenes intelligence sharing could be interpreted as indirect support for Egypt’s position, though it is aimed at confidence-building (preventing surprises) rather than undermining the dam. There is also the broader U.S. intelligence interest in regional reactions – for example, keeping tabs on any Egyptian military preparations or covert plans relating to GERD. So far, Egypt has not taken military action, and the CIA in 1986 had assessed an “Egyptian surgical attack” on an Ethiopian dam as “highly unlikely…for political and logistic reasons.” Instead, it noted Egypt might resort to clandestine efforts to impede a damcia.gov. To date, there’s no public evidence of Egyptian sabotage, but rumors (for instance, about mysterious incidents or unrest near the dam site) occasionally surface in regional media. U.S. intelligence would be keenly interested in such developments to prevent escalation, but those details remain classified. What is publicly available underscores that the U.S. intelligence community views water scarcity and GERD as critical factors in the stability of a volatile region, aligning with broader U.S. security concerns.

In summary, declassified CIA material confirms the U.S. has long been aware of the Nile’s potential to spark conflict and has evaluated various outcomes, but it does not indicate any covert U.S. hand in constructing GERD. If anything, the intelligence perspective reinforced U.S. diplomatic caution. The GERD dispute is essentially a regional issue that U.S. policymakers prefer to manage through diplomacy and international frameworks, rather than intelligence operations. The mention of CIA reports in this context primarily serves to highlight how seriously Washington takes the matter – literally considering scenarios of war and peace over water decades in advance.

Conclusion

After a comprehensive investigation, the evidence is clear that the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam was not financed by the United States, neither openly nor through hidden channels. Ethiopia self-financed the GERD with great national effort, supplemented modestly by Chinese loans for associated works – but no U.S. funds went into pouring its concrete or erecting its turbinesjwafs.mit.edubrookings.edu. On the contrary, at the peak of tensions the U.S. withdrew some financial support from Ethiopia as a form of pressurereuters.com. The U.S. role has instead been characterized by diplomatic engagement: convening negotiations, proposing compromises, and at times taking punitive measures when talks broke downsecurityincontext.comhome.treasury.gov. This stance reflects the broader geopolitical calculus the U.S. faces in the Nile Basin. Washington’s priorities are to uphold regional stability and prevent a water crisis from turning into conflict, all while juggling its commitments to key partners like Egypt and the strategic importance of Ethiopia and Sudan.

American strategic interest in the GERD issue is ultimately about preventing a lose-lose outcome. A negotiated agreement would allow Ethiopia to generate the electricity it desperately seeks from GERD (powering development for millions), while assuring Egypt and Sudan that their water needs and safety are protectedhome.treasury.gov. Such a win-win scenario aligns with U.S. goals of promoting development and stability. Conversely, an unchecked confrontation – whether diplomatic or military – could destabilize a region that is already fragile. Thus far, U.S. diplomacy, though imperfect, has helped keep the dialogue alive (now mainly under African Union auspices) and signaled to both sides that compromise is essential. The CIA’s declassified warnings about water wars in the 1980scia.gov echo in today’s policy debates, reminding all parties of what is at stake.

In conclusion, there is no indication from official records, aid budgets, or credible reports that the U.S. ever funded the GERD’s construction or related infrastructure. U.S. involvement has been political, not financial – driven by the need to mitigate a delicate dispute between allies and avoid a broader regional fallout. As the GERD nears completion and filling progresses (with the reservoir now substantially filled in stages through 2020–2024), the United States continues to advocate for a balanced agreement. American officials have expressed that a “transformational” deal on GERD could foster regional cooperation, economic integration, and peacehome.treasury.gov – outcomes very much in the U.S. strategic interest. Achieving that will depend on the riparian countries themselves, with the U.S. and others playing supporting roles. What is certain is that the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam stands as an African-built project, and U.S. policy will remain focused on ensuring this grand dam becomes a source of cooperation rather than conflict in the Nile Basin.

Sources:

U.S. Department of the Treasury – Statement by Secretary Steven Mnuchin on GERD negotiations (Feb 28, 2020)home.treasury.govhome.treasury.gov.

Brookings Institution – “The controversy over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam” by John Mukum Mbakubrookings.edubrookings.edu.

MIT JWAFS Report – “The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam” (analysis of GERD financing and operations)jwafs.mit.edu.

Reuters – “U.S. to cut $100 million in aid to Ethiopia over GERD dispute” (Sep 2020)reuters.com.

Security in Context – “Great Power Competition in the Nile Basin” (media & positions of U.S., China, etc.)securityincontext.comsecurityincontext.com.

CIA (declassified) – “Egypt: Vulnerability of Nile Water Supply” (Intelligence Memorandum, 1986)cia.govcia.gov.

Wikipedia – “Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam” (background on project and funding)en.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org.