Forty years ago this week, a group of pop stars gathered at a west London studio to record a single that would raise millions, inspire further starry projects, and ultimately change charity fundraising in the UK.

Do They Know It’s Christmas, Bob Geldof and Midge Ure’s festive charity behemoth, would go on to raise almost £150m for famine relief and development in Ethiopia and elsewhere in Africa. To mark the anniversary, on Monday a new version of the single – its fifth – will be released under the name Band Aid 40.

Four decades on, however, is Band Aid doing harm as well as good? That was the suggestion of a statement made this week by Ed Sheeran, who sang on the version of the single released in 2014 and whose voice has been used in the new remix, along with other vocalists from across the decades.

He had not been asked permission, said Sheeran on Instagram, and would have declined if he had. Instead, he shared a post by the musician Fuse ODG, a longtime Band Aid critic, who argues such initiatives “perpetuate damaging stereotypes that stifle Africa’s economic growth, tourism and investment, ultimately … destroying its dignity, pride and identity”.

For all Band Aid’s popularity over the years, there are many in the development sector who share this view. Critics point to problematic lyrics – yes, they do know it is Christmas in Ethiopia, one of the oldest Christian communities in the world – and images of nameless, helpless victims.

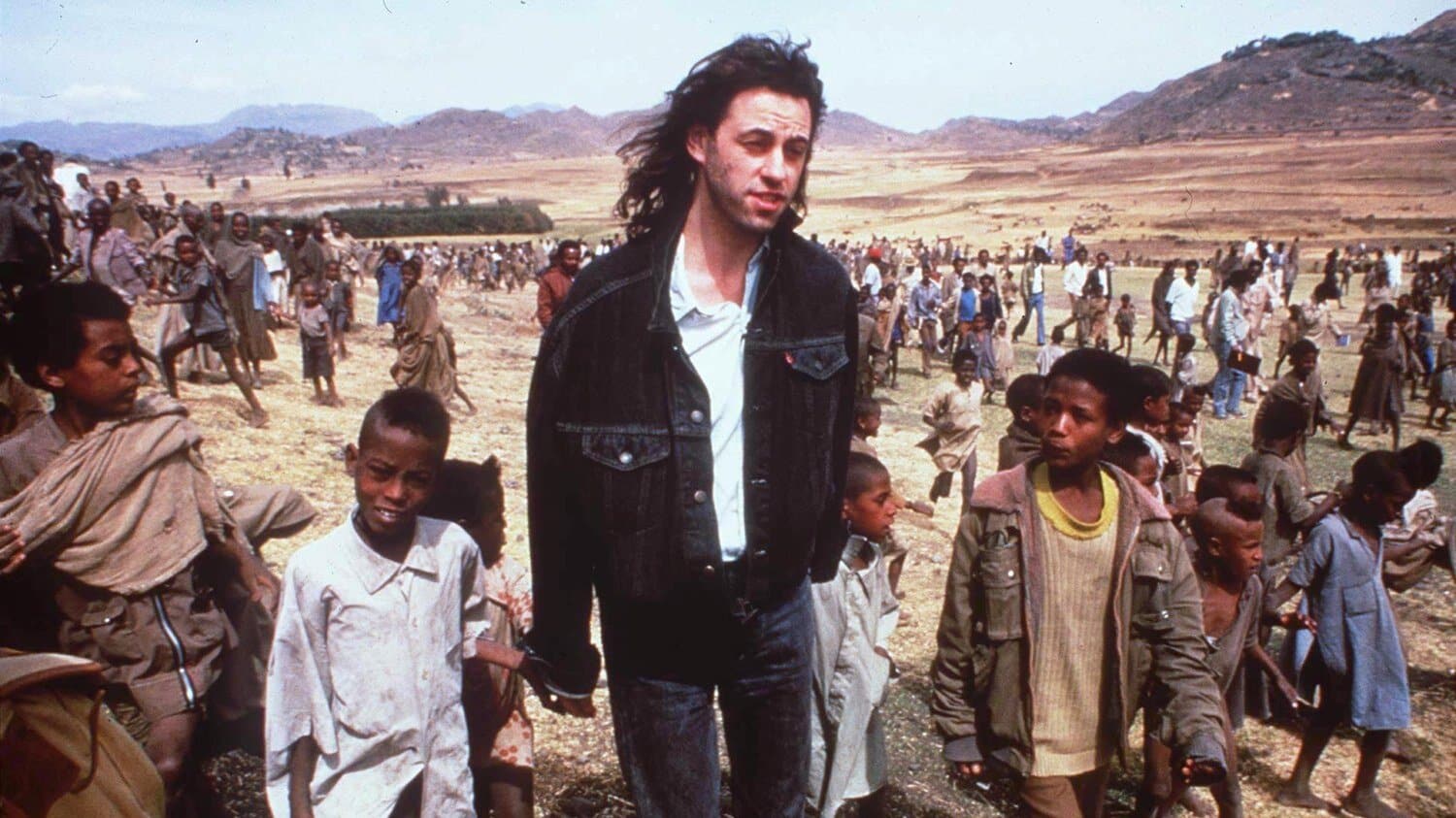

The problem is “Africa always [being] portrayed as a place where children are perpetually in peril,” said Haseeb Shabbir, an associate professor at the Centre for Charity Effectiveness at City St George’s, University of London. “Africa is [shown as] a barren civilisation in constant need of salvation, while it is portrayed as the moral obligation of essentially white donors to save a group of people who lack agency to resolve their own problems.”

Meanwhile, he said, “many initiatives from African people themselves go under the radar. Nobody hears about them in this country, [but] it’s those changes which are the bulk of what is taking place in Africa.”

Band Aid is far from alone in this, in Shabbir’s view – Comic Relief, which was inspired by it, has come in for similar criticism. “But the problem with Band Aid is that its message is so amplified and celebrated.” It is certainly remarkably enduring – alongside the countless radio plays and millions of streams of the original single each year, even Band Aid 30 a decade ago went to No 1 in 69 countries.

The international development sector has changed a lot in four decades, said Lena Bheeroo, head of anti-racism and equity at Bond, an umbrella body for development organisations, moving away from “images of poverty, disease, conflict and children who are malnourished with flies on them”, and the use of wording that reinforces recipients’ powerlessness.

“Band Aid was set up in a time where [using this imagery] was deemed the right thing to be doing. But we’re not any longer in 1984, we are in 2024, and the conversations around what it means to [work in this area] have changed.”

These are not new criticisms, as Geldof hit back tartly this week to the Conversation: “The same argument has been made many times over the years and elicits the same wearisome response.” Band Aid has made concessions to changing times in the past – the 2014 single had substantially changed lyrics, most strikingly changing Bono’s original line “Well tonight, thank God it’s them instead of you” to “ell tonight, we’re reaching out and touching you.” Emeli Sandé, who sang on that track, later apologised for it, however, saying other edits she made had not been included.

Band Aid did not confirm which lyrics and imagery were used in the new release.

Geldof’s response to such criticism has always been to point to what Band Aid has achieved. “This little pop song has kept hundreds of thousands if not millions of people alive,” he said this week. “In fact, just today Band Aid has given hundreds of thousands of pounds to help those running from the mass slaughter in Sudan and enough cash to feed a further 8,000 children in the same affected areas of Ethiopia as 1984.” Those helped, he added, “will sleep safer, warmer and cared for tonight because of that miraculous little record.”

His defenders also argue that after four decades, Geldof is well informed on the structural and political causes of poverty and has been actively engaged in advocacy alongside African leaders for many years.

And it is true that the projects funded by the Band Aid Charitable Trust – which distributed more than £3m last year – do many admirable things, often in long-term initiatives such as providing clean water, building schools and libraries and providing training to prevent gender-based violence.

A spokesperson for the charity Mary’s Meals UK, which has been supported by Band Aid since 2010 to provide school meals for children in Tigray, Ethiopia, reaching 110,000 last year, said its projects were “a direct response to what local communities told us they needed in the wake of the conflict and the crippling drought”.

Shabbir said he hoped those supporting Band Aid this year would also take the opportunity to find out more. “If you are giving £5 – that’s great. Now go on to the next stage and learn what’s taking place in Africa. Learn about structural inequalities, learn about power dynamics and be part of the story from the African side of the narrative as well.”

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you move on, I wanted to ask if you would consider supporting the Guardian’s work during our most important annual fundraising appeal.

As we face a second Trump presidency, our reporters have never been more passionate about exposing threats to our democracy and holding power to account in America. Our country is in urgent need of free, trustworthy journalism – especially with a president-elect who has repeatedly called the press “the enemy of the people” and has said journalists should be “thoroughly scrutinized” and “pay a big price” for their work.

It has never been clearer that media ownership matters to democracy. Our country is deeply divided, and those divisions are also being exploited by bad actors looking to enrich themselves and undermine our democracy by spreading disinformation. From Elon Musk to the Murdochs, a small number of billionaire owners have a powerful hold on so much of the information that reaches the public about what’s happening in the world.

The Guardian is different. We have no billionaire owner or shareholders to consider. Our journalism is produced to serve the public interest – not profit motives.

Largely because of this independence, we are able to avoid the trap that befalls much US media: the tendency, born of a desire to please all sides, to engage in false equivalence in the name of neutrality. The way we see it, our job is to be truly fair, which means listening to different points of view, but also calling out the lies of powerful people and institutions – and making clear how misinformation and demagoguery can damage democracy.

From threats to our democracy, to the spiraling climate crisis, to complex foreign conflicts, our journalists contextualize, investigate and illuminate the critical stories of our time. As a global news organization with a robust US reporting staff, we’re able to provide a fresh, outsider perspective – one so often missing in the American media bubble.

Around the world, readers can access the Guardian’s paywall-free journalism because of our unique reader-supported model. That’s because of people like you. Our readers keep us independent, beholden to no outside influence and accessible to everyone – whether they can afford to pay for news, or not.

If you can, please consi