Adrian Ma from NPR engages in a discussion with Cerian Richmond Jones of The Economist regarding the recent choice made by the governments of Nigeria and Ethiopia to allow their currencies to float.

ADRIAN MA, HOST:

Two of the largest economies in Africa are implementing significant measures to stabilize their financial systems. Recently, Ethiopia and Nigeria have encountered critical challenges, including soaring inflation, increasing debt levels, and difficulties in attracting foreign investment. In response to these issues, both nations have transitioned from a fixed exchange rate system to a floating exchange rate system, a move that may seem unconventional. Essentially, adopting a floating currency means that the government relinquishes control over the exchange rate, allowing market forces to determine its value. This is a courageous decision that carries the potential risk of exacerbating economic difficulties for the citizens of Nigeria and Ethiopia if the transition does not proceed successfully.

To further elucidate the implications of this decision, we are joined by Cerian Richmond Jones, a reporter for The Economist who specializes in economic developments in the Global South. Cerian, we appreciate your presence on ALL THINGS CONSIDERED.

To begin our discussion, could you elaborate on the significance of a country opting to float its currency’s exchange rate?

The situation is significant, not only due to the size and importance of countries like Ethiopia and Nigeria, which each have populations in the hundreds of millions, but also because of the profound effects on the daily lives of these individuals. When a government decides to float its currency, it typically results in a sharp decline in value. This decline often occurs after the government has expended considerable resources attempting to stabilize and enhance the currency’s worth. Consequently, the prices of essential imports, particularly food and fuel, rise dramatically, placing a heavy burden on the populace.

This scenario leads to a crisis in the cost of living. While, in theory, exports should become more affordable, benefiting manufacturers, the positive impacts on the economy take significantly longer to materialize compared to the immediate adverse effects felt by consumers due to rising import prices. Currently, in Nigeria, which floated its currency a year ago, there are widespread protests involving hundreds of thousands of citizens expressing their frustration over soaring food and fuel costs. Many individuals are voicing concerns about their inability to provide adequate nutrition for their children, highlighting the severity of the situation.

MA: It’s almost like the medicine hurts more than the cure, which is still kind of a ways off.

JONES: Yeah, absolutely. And the real risk is that that cure never comes through.

MA: Ethiopia decided to float its currency last month, Nigeria about a year ago. Why is it tricky or even risky for these economies to float their currency?

JONES: It’s really risky. These currencies have been fixed because the government wants to make them more valuable because that makes imports cheaper, right? And that often means that when they float them, they don’t actually know where they’re going to settle. And so what we’ve seen in other countries, such as Egypt, is that…

MA: Right. They decided to float their currency earlier this year.

JONES: Yes. And it’s much bigger, often, than policymakers are anticipating. So you can kind of imagine a situation where you think that your currency is going to lose about 10% of its value when the market decides on its value rather than the government. And actually, often, that dip ends up much bigger than governments are anticipating. So you get much more inflation than you were thinking about.

And politically, it’s a complete gamble as well because what you’re asking your citizens to do is understand quite complex economics. You’re understanding them – you’re asking them to understand that they have to kind of take this real hard hit to their consumption, to their daily life now, in order to maybe gain down the line, kind of four, five years in advance. And the populations of Ethiopia and Nigeria are angry. Their governments have a lot of problems anyway. And I think what we’re seeing is that that’s a really, really difficult trade-off to communicate and ask populations to make.

MA: Thus, the protests that we’ve seen in recent weeks over the cost of living.

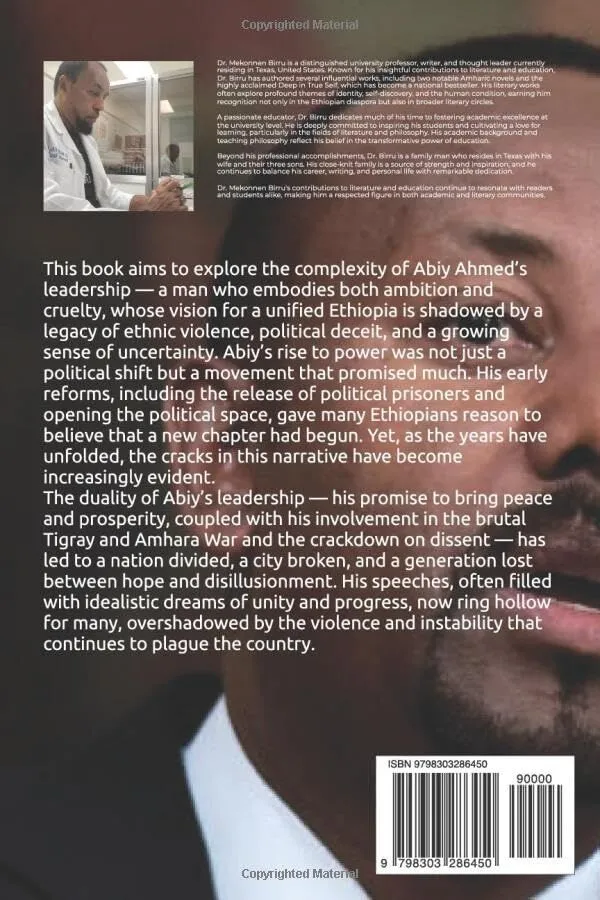

JONES: Yeah, exactly – in Nigeria. And when we look at kind of what’s happened to Ethiopia in the last few years, the social situation there seems even more caustic and likely to catch fire than Nigeria’s does. A lot of people are talking about how the government’s priority should be – as conflict dies down, should be reconstruction and spending rather than fiddling around with the currency. So all of these things put more and more pressure on the politics as well.

MA: Last question – in a recent piece in The Economist, you wrote about Ethiopia and Nigeria, and you ended by saying, quote, “unless it’s matched by changes at home, currency reform will do little to put the two economies on a more sustainable footing.” Can you just explain what you mean by that?

JONES: So what we mean by that is that it’s all well and good when a government messes around or fixes problems with the currency. It gives a bit of a boost to the manufacturing sector, and it gives a boost to exports. So this should make Ethiopia and Nigeria’s exports more attractive, which is the kind of upside. We’ve been talking a lot about the downsides, but that’s the upside.

The problem with that is that the manufacturing sector will only really start going and start being boosted if the government has the right policy in place, and that goes far beyond currency. Particularly, Ethiopia is one of the most kind of unorthodox economies in the world. It looks very little like the United States. Most of the economy is owned by the government. All the big firms are run by the state. Capital controls are all over the place.

And currency reform is the – it’s kind of the last step, often, that economies take. So really, the governments of Ethiopia and Nigeria have kind of pulled the rug out of the economies that they govern, and there’s still all this other stuff, all this more fundamental stuff that they still have to do. And no one really knows how the chips are going to fall.

MA: We’ve been speaking with Cerian Richmond Jones of The Economist. Cerian, thanks so much for taking the time.

JONES: Thank you so much.

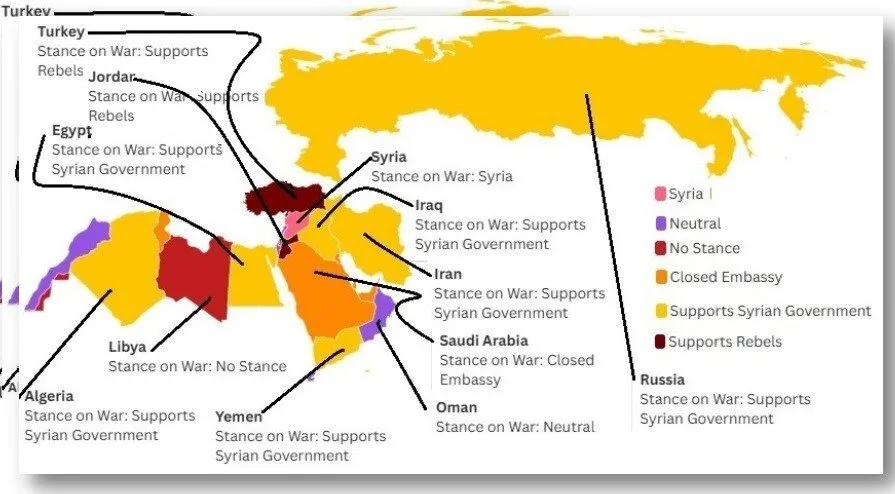

No need to worry or talk about the doomsday consequences of this currency floating decision by Nigeria and Ethiopia. That is because the might armies of Villa Mogadishu, Egypt, Piccolo Roma armed to the teeth and assisted by the armies of the Pasha in Ankara have reached the outskirts of Addis/Finfinne. Abiy is reported to have fled the country is now living in abandoned building in Minnesota, Toronto, Tennessee and Oslo surrounded by adoring bigots and connivers. Did I tell you Abiy’s mother was a Filipina and his father was a Maori? Jula has fled to Rwanda to join his Tutsi family. The president is of Creole descent on her mother’s side and a Chickasaw on her father’s side. She is now in New Orleans having good time in the French Quarter. The defense minister Aisha bint Mohammed fled to her country of Oman and she is now in Muscat where she was put in charge of the military by her first cousin, the king of Oman. So your Ethiopia is done, dead and gone. I don’t any mouth from talking about Ethiopia this or Ethiopia that anymore.