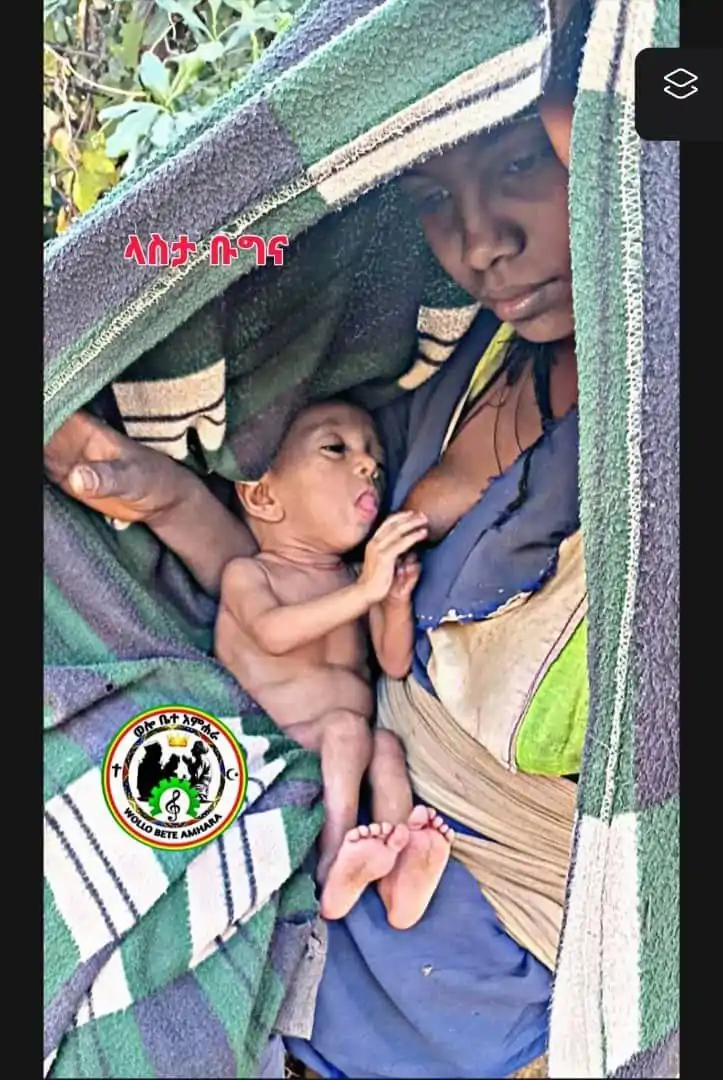

The new village of Bildak in Ethiopia’s Gambella region, which the semi-nomadic Nuer who were forcibly transferred there quickly abandoned in May 2011 because there was no water source for their cattle.

© 2011 Human Rights Watch

Update: A World Bank board meeting scheduled for March 19, 2013, to consider the recommendation of its Inspection Panel to investigate whether the bank has violated its policies in a project in Ethiopia has been postponed to an unspecified date. The project was linked to the Ethiopian government’s resettlement program, known as “villagization,” which Human Rights Watch has criticized for resulting in widespread human rights violations.

“The World Bank’s president and board should support an internal investigation into the plagued Ethiopia project without delay,” said Jessica Evans, senior international financial institutions advocate at Human Rights Watch. “The longer the investigation is delayed, the longer the shadow of controversy will remain over this project.”

————————

(Washington, DC) – The World Bank’s board should support an internal investigation into allegations of abuse linked to a World Bank project in Ethiopia, Human Rights Watch said today.

The Inspection Panel, the World Bank’s independent accountability mechanism, has recommended an investigation into whether it has violated its policies in a project linked to the Ethiopian government’s resettlement program, known as “villagization.” Villagization involves the forced relocation of some 1.5 million Ethiopians, including indigenous and other marginalized peoples, and has been marred by violence. The board is scheduled to meet on March 19, 2013, to consider the Inspection Panel’s recommendation.

“The World Bank’s president and board need to let the Inspection Panel do its job and answer the critical questions that have been raised by Ethiopians affected by this project,” said Jessica Evans, senior international financial institutions advocate at Human Rights Watch. “If the World Bank doesn’t support this investigation, its Ethiopia program will continue to be shadowed by controversy.”

On September 24, 2012, several Ethiopians brought a complaint to the Inspection Panel, pressing the World Bank to apply its safeguard policies in an Ethiopia project. The safeguard policies are designed to prevent and mitigate undue harm in World Bank projects, including protecting the rights of indigenous peoples and preventing abuses related to involuntary resettlement.

The World Bank went ahead and approved the project the next day and has not applied its safeguard policies to the project.

The Inspection Panel, which reports directly to the World Bank’s board of executive directors, subsequently found that the complaint warranted a full investigation. This recommendation would have been endorsed by the board in February, but action has been delayed because the executive director representing Ethiopia has requested a discussion of the panel’s finding and recommendation.

Human Rights Watch research has found that many of the largely indigenous communities being moved in Gambella, one region where “villagization” is being carried out, have not been consulted about the resettlement process and that the government responded with violence and arbitrary detentions when people have not agreed to move.

A 20-year-old Ethiopian man who escaped to Kenya told Human Rights Watch, “Soldiers came and asked me why I refused to be relocated.… They started beating me until my hands were broken … I ran to tell [my father] what had happened, but the soldiers followed me. My father and I ran away.… I heard the sound of gunfire.” He heard his father cry out, but he kept running and hid from the soldiers in the bushes as he was “full of fear.” When he returned the next day, he learned that the soldiers had killed his father.

Once forced into new villages, families have found that the promised government services often do not exist, giving them less access to services than before the relocation. The government has also failed to provide compensation. Dozens of farmers in Ethiopia’s Gambella region told Human Rights Watch they are being moved from fertile areas where they survive on subsistence farming, to dry, arid areas. Many villagers believe that the fertile land from which they have been removed is being leased to multinational companies for large-scale farms.

The project in question is known as the Promotion of Basic Services (PBS) and is intended to improve education, health care, water and sanitation, agriculture, and rural roads. But, through this project, the World Bank is contributing to the salaries of local government staff who have been required to assist in implementing “villagization.”

Despite the human rights risks that “villagization” presents for the World Bank’s project,it has not applied its own safeguard policies. Its policy to protect indigenous people has not been applied in Ethiopia because the government does not agree that it should apply. Nor has the World Bank applied its policy on involuntary resettlement, which requires consultation and compensation when people are resettled.

The Inspection Panel recommended that it undertake a full investigation after a preliminary assessment that included interviewing Ethiopian refugees who have fled “villagization” and meeting with the Ethiopian government and donors. The Inspection Panel found the links between the World Bank’s basic services program and “villagization” to be plausible and to warrant investigation.

“Ethiopia is in great need of development aid, and its people have urgent social and economic needs that the World Bank should work to address,” Evans said. “But development by force is not development at all and Ethiopia should not be an exception to the World Bank’s commitment to upholding its own policies.”