The Amhara people are mostly agriculturist, one of the most culturally dominant and a powerful politically connected as well as Afro-Asiatic speaking ethnic group of ancient semitic origins inhabiting the northern and central highlands of Ethiopia, particularly the Amhara Region. The Amhara State shares common borders with the state of Tigray in the north, Afar in the east, Oromiya in the south, Benishangul/Gumuz in the south west, and the Republic of Sudan in the west.

The Amhara people are closely related with the Gurage, and the Tigray-Tigrinya people. The Amhara combined with the Gurage, and the Tigray-Tigrinya people are called the Habesha ( (Ge’ez: ሐበሻ Ḥabaśā, Amharic (H)ābešā, Tigrinya: ? Ḥābešā; Arabic: الحبشة al-Ḥabašah) people or Abyssinians.

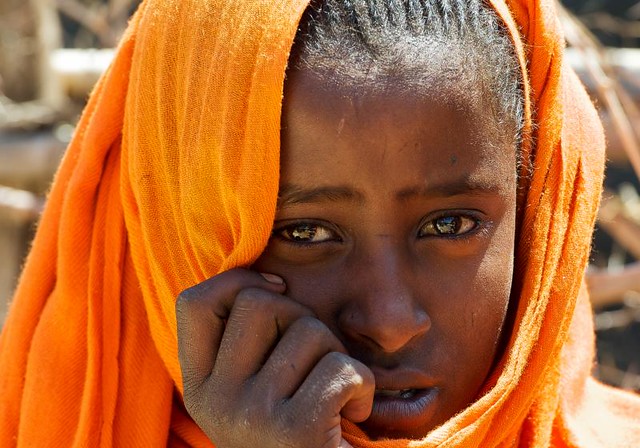

Amhara girls

The State of Amhara covers an estimated area of 170,752 square kilometres and consists of 10 administrative zones, one special zone, 105 woredas, and 78 urban centres. The capital city of the State of Amhara is Bahir-Dar. According to recent National Population Census, the Amhara constitute about 23 million people, making up to comprising 30.1% of the country’s population. Majority of the Amhara population can be found specifically in the provinces of Begender, Gojjam, Wallo, some parts of Shoa and the mountainous areas of Amhara state.

The Amhara who are the second largest ethnolinguistic group after the Oromo people are descendants of ancient Semitic conquerors who migrated southward to mingled with indigenous Cushitic peoples (Oromos) built the powerful ancient Kingdom of Aksum in Ethiopia. They claim ancestry through Shem the eldest son of biblical Noah and trace their lineage all the way to King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba; aw well as the legendary ancient King Menelik I. They carried that same ancestral line all the way to 1974 with Emperor Haile Selassie. Also, about 50 % of the Amhara are part of what is known as the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, which is an ancient Christian church founded around the 4th century. The Amhara do have their rituals and ceremonies, including the annual Coptic and national holidays and the monthly saints’ days. In addition, daily and monthly rites celebrate spirits whose identity lies outside the teachings of the Ethiopian Church.

The Amhara are ardent animal husbandry people, about 40% of the livestock population in Ethiopia are found in their territory. The huge livestock potential of this region gives ample opportunity for meat and milk production, food processing as well as leather and wool production. The Sate of Amhara also has mineral resources such as coal, shell, limestone, lignite, gypsum, gemstone, silica, sulfur and bentonite. Hot springs and mineral water are also found in the region.

Most importantly the Amhara state has great tourism and heritage industry. The 12th century Rock-Hewn churches of Lalibela, and the palaces in Gondar are some of the world known heritages. The traditional mural paintings and hand craft, the preserved corpse of the royalty found in the ancient monasteries in Lake Tana, as well as the Semien mountains national park, which shelters the endemic Walia ibex are spectacular tourist attractions, Three tourist attractions found in the region are registered in the UNESCO list of world heritages. Besides these known heritages, the Blue Nile Falls, the caves and unique stones in northern Showa, and the Merto Le Mariam church are special tourist attractions.

Origin of the Name Amhara

The etymology of the name Amhara has different sources. It is said that the ethnolinguistic name (the language and its speakers) Amhara comes from the medieval province of Amhara, located around Lake Tana at the headwaters of the Blue Nile and including a slightly larger area than Ethiopia’s present Amhara Region.

Other people trace it to amari (“pleasing; beautiful; gracious”) or mehare (“gracious”). The Ethiopian historian Getachew Mekonnen Hasen traces it to an ethnic name related to the Himyarites of ancient Yemen. Still others say that it derives from Ge’ez ዓም (ʿam, “people”) and ሓራ (h.ara, “free” or “soldier”), although this has been dismissed by scholars such as Donald Levine as a folk etymology.

Beautiful Amhara children from Ethiopia

Beautiful Amhara children from Ethiopia

Geography and Climate

The State of Amhara is topographically divided into two main parts, namely the highlands and lowlands. The highlands are above 1500 meters above sea level and comprise the largest part of the northern and eastern parts of the region. The highlands are also characterized by chains of mountains and plateaus. Ras Dejen (4620 m), the highest peak in the country, Guna (4236 m), Choke (4184m) and Abune – Yousef (4190m) are among the mountain peaks that are located in the highland parts of the region.

The lowland part covers mainly the western and eastern parts with an altitude between 500-1500 meters above sea level. Areas beyond 2,300 meters above sea level fall within the “Dega” climatic Zone, and areas between the 1,500-2,300 meter above sea level contour fall within the “Woina Dega” climatic zone; and areas below 1,500 contour fall within the “Kolla” or hot climatic zones. The Dega, Woina Dega and Kolla parts of the region constitute 25%, 44% and 31% of the total area of the region, respectively.

The annual mean temperature for most parts of the region lies between 15°C-21°C. The State receives the highest percentage (80%) of the total rainfall in the country. The highest rainfall occurs during the summer season, which starts in mid June and ends in early September.

The State of Amhara is divided mainly by three river basins, namely the Abbay, Tekezze and Awash drainage basins. The Blue Nile (Abbay) river is the largest of all covering approximately 172,254 Km2. Its total length to its junction with the white Nile in Khartoum is 1,450 Km, of which 800 km is within Ethiopia. The drainage-basin of the Tekeze river is about 88,800 km2. In addition, Anghereb, Millie, Kessem and Jema are among the major national rivers, which are found in this region.

Tana, the largest lake in Ethiopia is located at centre of the region. It covers an area of 3,6000 km2. Besides, other crater lakes like Zengeni, Gudena Yetilba, Ardibo (75km2) and Logia (35 km2) are small lakes that are found in the region.

The rivers and lakes of the region have immense potential for hydroelectric power generation, irrigation and fishery development.

Blue Nile

Walia ibex, Semien fox, Gelada-baboon, Grey Duiker, Klipspringer, Hyenas and Corocodile are among the twenty-one species (three endemic) that are found in the region, especially at the Semien mountain national park. Wild fowls, Francolins, Pelicans, Cranes, Ibises, and Stocks are among the birds that are found in the region.

Amhara plateau

Amhara plateau

Myths (Creation):

It is said that Eve had thirty children, and one day God asked Eve to show Him her children. Eve became suspicious and apprehensive and hid fifteen of them from the sight of God. God knew her act of disobedience and declared the fifteen children she showed God as His chosen children and cursed the fifteen she hid, declaring that they go henceforth into the world as devils and wretched creatures of the earth. Now some of the children complained and begged God’s mercy. God heard them and, being merciful, made some of them foxes, jackals, rabbits, etc., so that they might exist as Earth’s creatures in a dignified manner. Some of the hidden children he left human, but sent them away with the curse of being agents of the devil. These human counterparts of the devil are the ancestors of the buda people. There occurs a pleat in time and the story takes up its theme again when Christ was baptized at age thirty.

Language

There is no agreed way of transliterating Amharic into Roman characters. The Amharic examples in the sections below use one system that is common, though not universal, among linguists specializing in Ethiopian Semitic languages.

Writing system

The Amharic script is an abugida, and the graphs of the Amharic writing system are called fidel. Each character represents a consonant+vowel sequence, but the basic shape of each character is determined by the consonant, which is modified for the vowel. Some consonant phonemes are written by more than one series of characters: /ʔ/, /s/, /sʼ/, and /h/ (the last one has four distinct letter forms). This is because these fidel originally represented distinct sounds, but phonological changes merged them. The citation form for each series is the consonant+ä form, i.e. the first column of the fidel. A font that supports Ethiopic, such as GF Zemen Unicode, is needed to see fidel on typical modern computer systems.Alphabet

Chart of Amharic fidels

| ä [ə] | u | i | a | e | ə [ɨ], ∅ | o | ʷä [ʷə] | ʷi | ʷa | ʷe | ʷə [ʷɨ] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| h | ሀ | ሁ | ሂ | ሃ | ሄ | ህ | ሆ | ||||||

| l | ለ | ሉ | ሊ | ላ | ሌ | ል | ሎ | ሏ | |||||

| h | ሐ | ሑ | ሒ | ሓ | ሔ | ሕ | ሖ | ሗ | |||||

| m | መ | ሙ | ሚ | ማ | ሜ | ም | ሞ | ሟ | |||||

| s | ሠ | ሡ | ሢ | ሣ | ሤ | ሥ | ሦ | ሧ | |||||

| r | ረ | ሩ | ሪ | ራ | ሬ | ር | ሮ | ሯ | |||||

| s | ሰ | ሱ | ሲ | ሳ | ሴ | ስ | ሶ | ሷ | |||||

| ʃ | ሸ | ሹ | ሺ | ሻ | ሼ | ሽ | ሾ | ሿ | |||||

| q | ቀ | ቁ | ቂ | ቃ | ቄ | ቅ | ቆ | ቈ | ቊ | ቋ | ቌ | ቍ | |

| b | በ | ቡ | ቢ | ባ | ቤ | ብ | ቦ | ቧ | |||||

| v | ቨ | ቩ | ቪ | ቫ | ቬ | ቭ | ቮ | ቯ | |||||

| t | ተ | ቱ | ቲ | ታ | ቴ | ት | ቶ | ቷ | |||||

| tʃ | ቸ | ቹ | ቺ | ቻ | ቼ | ች | ቾ | ቿ | |||||

| ħ | ኀ | ኁ | ኂ | ኃ | ኄ | ኅ | ኆ | ኈ | ኊ | ኋ | ኌ | ኍ | |

| n | ነ | ኑ | ኒ | ና | ኔ | ን | ኖ | ኗ | |||||

| ɲ | ኘ | ኙ | ኚ | ኛ | ኜ | ኝ | ኞ | ኟ | |||||

| ʔ | አ | ኡ | ኢ | ኣ | ኤ | እ | ኦ | ኧ | |||||

| k | ከ | ኩ | ኪ | ካ | ኬ | ክ | ኮ | ኰ | ኲ | ኳ | ኴ | ኵ | |

| x | ኸ | ኹ | ኺ | ኻ | ኼ | ኽ | ኾ | ||||||

| w | ወ | ዉ | ዊ | ዋ | ዌ | ው | ዎ | ||||||

| ʔ | ዐ | ዑ | ዒ | ዓ | ዔ | ዕ | ዖ | ||||||

| z | ዘ | ዙ | ዚ | ዛ | ዜ | ዝ | ዞ | ዟ | |||||

| ʒ | ዠ | ዡ | ዢ | ዣ | ዤ | ዥ | ዦ | ዧ | |||||

| j | የ | ዩ | ዪ | ያ | ዬ | ይ | ዮ | ||||||

| d | ደ | ዱ | ዲ | ዳ | ዴ | ድ | ዶ | ዷ | |||||

| dʒ | ጀ | ጁ | ጂ | ጃ | ጄ | ጅ | ጆ | ጇ | |||||

| g | ገ | ጉ | ጊ | ጋ | ጌ | ግ | ጎ | ጐ | ጒ | ጓ | ጔ | ጕ | |

| t’ | ጠ | ጡ | ጢ | ጣ | ጤ | ጥ | ጦ | ጧ | |||||

| tʃ’ | ጨ | ጩ | ጪ | ጫ | ጬ | ጭ | ጮ | ጯ | |||||

| p’ | ጰ | ጱ | ጲ | ጳ | ጴ | ጵ | ጶ | ጷ | |||||

| ts’ | ጸ | ጹ | ጺ | ጻ | ጼ | ጽ | ጾ | ጿ | |||||

| ts’ | ፀ | ፁ | ፂ | ፃ | ፄ | ፅ | ፆ | ||||||

| f | ፈ | ፉ | ፊ | ፋ | ፌ | ፍ | ፎ | ፏ | |||||

| p | ፐ | ፑ | ፒ | ፓ | ፔ | ፕ | ፖ | ፗ | |||||

| ä [ə] | u | i | a | e | ə [ɨ], ∅ | o | ʷä [ʷə] | ʷi | ʷa | ʷe | ʷə [ʷɨ] | ||

Gemination[edit]

As in most other Ethiopian Semitic languages, gemination is contrastive in Amharic. That is, consonant length can distinguish words from one another; for example, alä ‘he said’, allä ‘there is’; yǝmätall ‘he hits’, yǝmmättall ‘he is hit’. Gemination is not indicated in Amharic orthography, but Amharic readers typically do not find this to be a problem. This property of the writing system is analogous to the vowels of Arabic and Hebrew or the tones of many Bantu languages, which are not normally indicated in writing. The noted Ethiopian novelist Haddis Alemayehu, who was an advocate of Amharic orthography reform, indicated gemination in his novel Fǝqǝr Əskä Mäqabǝr by placing a dot above the characters whose consonants were geminated, but this practice is rare.

Punctuation

Punctuation includes:

፠ section mark

፡ word separator

። full stop (period)

፣ comma

፤ semicolon

፥ colon

፦ Preface colon (introduces speech from a descriptive prefix)

፧ question mark

፨ paragraph separator

Grammar

Simple Amharic sentences

One may construct simple Amharic sentences by using a subject and a predicate. Here are a few simple sentences:

ʾItyop̣p̣ya ʾAfriqa wəsṭ nat

(lit., Ethiopia Africa inside is)

‘Ethiopia is in Africa.’

Ləǧu täññətʷall.

(lit., boy is.asleep)

‘The boy is asleep.’

Ayyäru däss yəlall

(lit., weather good is)

‘The weather is good.’

Əssu wädä kätäma mäṭṭa.

(lit., he to city came)

‘He came to the city.’

Pronouns

Personal pronouns

In most languages, there is a small number of basic distinctions of person, number, and often gender that play a role within the grammar of the language. We see these distinctions within the basic set of independent personal pronouns, for example, English I, Amharic እኔ ǝne; English she, Amharic እሷ ǝsswa. In Amharic, as in other Semitic languages, the same distinctions appear in three other places within the grammar of the languages.

Subject–verb agreement

All Amharic verbs agree with their subjects; that is, the person, number, and (second- and third-person singular) gender of the subject of the verb are marked by suffixes or prefixes on the verb. Because the affixes that signal subject agreement vary greatly with the particular verb tense/aspect/mood, they are normally not considered to be pronouns and are discussed elsewhere in this article under verb conjugation.

Object pronoun suffixes

Amharic verbs often have additional morphology that indicates the person, number, and (second- and third-person singular) gender of the object of the verb.

አልማዝን አየኋት

almazǝn ayyähʷ-at

Almaz-ACC I-saw-her

‘I saw Almaz’

While morphemes such as -at in this example are sometimes described as signaling object agreement, analogous to subject agreement, they are more often thought of as object pronoun suffixes because, unlike the markers of subject agreement, they do not vary significantly with the tense/aspect/mood of the verb. For arguments of the verb other than the subject or the object, there are two separate sets of related suffixes, one with a benefactive meaning (to, for), the other with an adversative or locative meaning (against’, to the detriment of, on’, at).

ለአልማዝ በሩን ከፈትኩላት

läʾalmaz bärrun käffätku-llat

for-Almaz door-DEF-ACC I-opened-for-her

‘I opened the door for Almaz’

በአልማዝ በሩን ዘጋሁባት

bäʾalmaz bärrun zäggahu-bbat

on-Almaz door-DEF-ACC I-closed-on-her

‘I closed the door on Almaz (to her detriment)’

Morphemes such as -llat and -bbat in these examples will be referred to in this article as prepositional object pronoun suffixes because they correspond to prepositional phrases such as for her and on her, to distinguish them from the direct object pronoun suffixes such as -at ‘her’.

Possessive suffixes

Amharic has a further set of morphemes that are suffixed to nouns, signalling possession: ቤት bet ‘house’, ቤቴ bete, my house, ቤቷ; betwa, her house.

In each of these four aspects of the grammar, independent pronouns, subject–verb agreement, object pronoun suffixes, and possessive suffixes, Amharic distinguishes eight combinations of person, number, and gender. For first person, there is a two-way distinction between singular (I) and plural (we), whereas for second and third persons, there is a distinction between singular and plural and within the singular a further distinction between masculine and feminine (you m. sg., you f. sg., you pl., he, she, they).

Amharic is a pro-drop language. That is, neutral sentences in which no element is emphasized normally do not have independent pronouns: ኢትዮጵያዊ ነው ʾityop̣p̣yawi näw ‘he’s Ethiopian’, ጋበዝኳት gabbäzkwat ‘I invited her’. The Amharic words that translate he, I, and her do not appear in these sentences as independent words. However, in such cases, the person, number, and (second- or third-person singular) gender of the subject and object are marked on the verb. When the subject or object in such sentences is emphasized, an independent pronoun is used: እሱ ኢትዮጵያዊ ነው ǝssu ʾityop̣p̣yawi näw ‘he’s Ethiopian’, እኔ ጋበዝኳት ǝne gabbäzkwat ‘I invited her’, እሷን ጋበዝኳት ǝsswan gabbäzkwat ‘I invited her’.

The table below shows alternatives for many of the forms. The choice depends on what precedes the form in question, usually whether this is a vowel or a consonant, for example, for the 1st person singular possessive suffix, አገሬ agär-e ‘my country’, ገላዬ gäla-ye ‘my body’.

Amharic Personal Pronouns

| English | Independent | Object pronoun suffixes | Possessive suffixes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Prepositional | ||||

| Benefactive | Locative/Adversative | ||||

| I | እኔ ǝne | -(ä/ǝ)ñ | -(ǝ)llǝñ | -(ǝ)bbǝñ | -(y)e |

| you (m. sg.) | አንተ antä | -(ǝ)h | -(ǝ)llǝh | -(ǝ)bbǝh | -(ǝ)h |

| you (f. sg.) | አንቺ anči | -(ǝ)š | -(ǝ)llǝš | -(ǝ)bbǝš | -(ǝ)š |

| you (polite) | እርስዎ əswo | -(ə)wo(t) | -(ǝ)llǝwo(t) | -(ǝ)bbǝwo(t) | -wo |

| he | እሱ ǝssu | -(ä)w, -t | -(ǝ)llät | -(ǝ)bbät | -(w)u |

| she | እሷ ǝsswa | -at | -(ǝ)llat | -(ǝ)bbat | -wa |

| s/he (polite) | እሳቸው əssaččäw | -aččäw | -(ǝ)llaččäw | -(ǝ)bbaččäw | -aččäw |

| we | እኛ ǝñña | -(ä/ǝ)n | -(ǝ)llǝn | -(ǝ)bbǝn | -aččǝn |

| you (pl.) | እናንተ ǝnnantä | -aččǝhu | -(ǝ)llaččǝhu | -(ǝ)bbaččǝhu | -aččǝhu |

| they | እነሱ ǝnnässu | -aččäw | -(ǝ)llaččäw | -(ǝ)bbaččäw | -aččäw |

Within second- and third-person singular, there are two additional “polite” independent pronouns, for reference to people that the speaker wishes to show respect towards. This usage is an example of the so-called T-V distinction that is made in many languages. The polite pronouns in Amharic are እርስዎ ǝrswo ‘you (sg. polite)’. and እሳቸው ǝssaččäw ‘s/he (polite)’. Although these forms are singular semantically—they refer to one person—they correspond to third-person plural elsewhere in the grammar, as is common in other T-V systems. For the possessive pronouns, however, the polite 2nd person has the special suffix -wo ‘your sg. pol.’

For possessive pronouns (mine, yours, etc.), Amharic adds the independent pronouns to the preposition yä- ‘of’: የኔ yäne ‘mine’, ያንተ yantä ‘yours m. sg.’, ያንቺ yanči ‘yours f. sg.’, የሷ yässwa ‘hers’, etc.

Reflexive pronouns

For reflexive pronouns (‘myself’, ‘yourself’, etc.), Amharic adds the possessive suffixes to the noun ራስ ras ‘head’: ራሴ rase ‘myself’, ራሷ raswa ‘herself’, etc.

Demonstrative pronouns

Like English, Amharic makes a two-way distinction between near (‘this, these’) and far (‘that, those’) demonstrative expressions (pronouns, adjectives, adverbs). Besides number, as in English, Amharic also distinguishes masculine and feminine gender in the singular.

Amharic Demonstrative Pronouns

| Number, Gender | Near | Far | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Masculine | ይህyǝh(ǝ) | ያya |

| Feminine | ይቺyǝčči, ይህችyǝhǝčč | ያቺ yačči | |

| Plural | እነዚህǝnnäzzih | እነዚያǝnnäzziya | |

There are also separate demonstratives for formal reference, comparable to the formal personal pronouns: እኚህ ǝññih ‘this, these (formal)’ and እኒያ ǝnniya ‘that, those (formal)’.

The singular pronouns have combining forms beginning with zz instead of y when they follow a preposition: ስለዚህ sǝläzzih ‘because of this; therefore’, እንደዚያ ǝndäzziya ‘like that’. Note that the plural demonstratives, like the second and third person plural personal pronouns, are formed by adding the plural prefix እነ ǝnnä- to the singular masculine forms.

Nouns

Amharic nouns can be primary or derived. A noun like əgər ‘foot, leg’ is primary, and a noun like əgr-äñña ‘pedestrian’ is a derived noun.

Gender

Amharic nouns can have a masculine or feminine gender. There are several ways to express gender. An example is the old suffix -t for femininity. This suffix is no longer productive and is limited to certain patterns and some isolated nouns. Nouns and adjectives ending in -awi usually take the suffix -t to form the feminine form, e.g. ityop̣p̣ya-(a)wi ‘Ethiopian (m.)’ vs. ityop̣p̣ya-wi-t ‘Ethiopian (f.)’; sämay-awi ‘heavenly (m.)’ vs. sämay-awi-t ‘heavenly (f.)’. This suffix also occurs in nouns and adjective based on the pattern qət(t)ul, e.g. nəgus ‘king’ vs. nəgəs-t ‘queen’ and qəddus ‘holy (m.)’ vs. qəddəs-t ‘holy (f.)’.

Some nouns and adjectives take a feminine marker -it: ləǧ ‘child, boy’ vs. ləǧ-it ‘girl’; bäg ‘sheep, ram’ vs. bäg-it ‘ewe’; šəmagəlle ‘senior, elder (m.)’ vs. šəmagəll-it ‘old woman’; t’ot’a ‘monkey’ vs. t’ot’-it ‘monkey (f.)’. Some nouns have this feminine marker without having a masculine opposite, e.g. šärär-it ‘spider’, azur-it ‘whirlpool, eddy’. There are, however, also nouns having this -it suffix that are treated as masculine: säraw-it ‘army’, nägar-it ‘big drum’.

The feminine gender is not only used to indicate biological gender, but may also be used to express smallness, e.g. bet-it-u ‘the little house’ (lit. house-FEM-DEF). The feminine marker can also serve to express tenderness or sympathy.

Specifiers

Amharic has special words that can be used to indicate the gender of people and animals. For people, wänd is used for masculinity and set for femininity, e.g. wänd ləǧ ‘boy’, set ləǧ ‘girl’; wänd hakim ‘physician, doctor (m.)’, set hakim ‘physician, doctor (f.)’. For animals, the words täbat, awra, or wänd (less usual) can be used to indicate masculine gender, and anəst or set to indicate feminine gender. Examples: täbat t’əǧa ‘calf (m.)’; awra doro ‘cock (rooster)’; set doro ‘hen’.

Plural

The plural suffix -očč is used to express plurality of nouns. Some morphophonological alternations occur depending on the final consonant or vowel. For nouns ending in a consonant, plain -očč is used: bet ‘house’ becomes bet-očč ‘houses’. For nouns ending in a back vowel (-a, -o, -u), the suffix takes the form -ʷočč, e.g. wəšša ‘dog’, wəšša-ʷočč ‘dogs’; käbäro ‘drum’, käbäro-ʷočč ‘drums’. Nouns that end in a front vowel pluralize using -ʷočč or -yočč, e.g. ṣähafi ‘scholar’, ṣähafi-ʷočč or ṣähafi-yočč ‘scholars’. Another possibility for nouns ending in a vowel is to delete the vowel and use plain očč, as in wəšš-očč ‘dogs’.

Besides using the normal external plural (-očč), nouns and adjectives can be pluralized by way of reduplicating one of the radicals. For example, wäyzäro ‘lady’ can take the normal plural, yielding wäyzär-očč, but wäyzazər ‘ladies’ is also found (Leslau 1995:173).

Some kinship-terms have two plural forms with a slightly different meaning. For example, wändəmm ‘brother’ can be pluralized as wändəmm-očč ‘brothers’ but also as wändəmmam-ač ‘brothers of each other’. Likewise, əhət ‘sister’ can be pluralized as əhət-očč (‘sisters’), but also as ətəmm-am-ač ‘sisters of each other’.

In compound words, the plural marker is suffixed to the second noun: betä krəstiyan ‘church’ (lit. house of Christian) becomes betä krəstiyan-očč ‘churches’.

Archaic forms

Amsalu Aklilu has pointed out that Amharic has inherited a large number of old plural forms directly from Classical Ethiopic (Ge’ez) (Leslau 1995:172). There are basically two archaic pluralizing strategies, called external and internal plural. The external plural consists of adding the suffix -an (usually masculine) or -at (usually feminine) to the singular form. The internal plural employs vowel quality or apophony to pluralize words, similar to English man vs. men and goose vs. geese. Sometimes combinations of the two systems are found. The archaic plural forms are sometimes used to form new plurals, but this is only considered grammatical in more established cases.

Examples of the external plural: mämhər ‘teacher’, mämhər-an; t’äbib ‘wise person’, t’äbib-an; kahən ‘priest’, kahən-at; qal ‘word’, qal-at.

Examples of the internal plural: dəngəl ‘virgin’, dänagəl; hagär ‘land’, ahəgur.

Examples of combined systems: nəgus ‘king’, nägäs-t; kokäb ‘star’, käwakəb-t; mäs’əhaf ‘book’, mäs’ahəf-t.

Definiteness

If a noun is definite or specified, this is expressed by a suffix, the article, which is -u or -w for masculine singular nouns and -wa, -itwa or -ätwa for feminine singular nouns. For example:

| masculine sg | masculine sg definite | feminine sg | feminine sg definite |

|---|---|---|---|

| bet | bet-u | gäräd | gärad-wa |

| house | the house | maid | the maid |

In singular forms, this article distinguishes between the male and female gender; in plural forms this distinction is absent, and all definites are marked with -u, e.g. bet-očč-u ‘houses’, gäräd-očč-u ‘maids’. As in the plural, morphophonological alternations occur depending on the final consonant or vowel.

Accusative

Amharic has an accusative marker, -(ə)n. Its use is related to the definiteness of the object, thus Amharic shows differential object marking. In general, if the object is definite, possessed, or a proper noun, the accusative must be used (Leslau 1995: pp. 181 ff.).

| ləǧ-u | wəšša-w-ən | abbarär-ä. | |

| child-def | dog-def-acc | chase-3msSUBJ | |

| ‘The child chased the dog.’ | |||

| *ləǧ-u | wəšša-w | abbarär-ä. | |

| child-def | dog-def | chase-3msSUBJ | |

| ‘The child chased the dog.’ | |||

| Yəh-ən | sä’at | gäzz-ä. |

| this-acc | watch | buy-3msSUBJ |

Dialects

There has not been much published about Amharic dialect differences. All dialects are mutually intelligible, but certain minor variations are noted.

Mittwoch described a form of Amharic spoken by the descendants of Weyto language speakers, but it was likely not a dialect of Amharic so much as the result of incomplete language learning as the community shifted languages from Weyto to Amharic.

Literature

There is a growing body of literature in Amharic in many genres. This literature includes government proclamations and records, educational books, religious material, novels, poetry, proverb collections, dictionaries (monolingual and bilingual), technical manuals, medical topics, etc. The Holy Bible was first translated into Amharic by Abu Rumi in the early 19th century, but other translations of the Bible into Amharic have been done since. The most famous Amharic novel is Fiqir Iske Meqabir (transliterated various ways) by Haddis Alemayehu (1909–2003), translated into English by Sisay Ayenew with the title Love unto Crypt, published in 2005 (ISBN 978-1-4184-9182-6).

Rastafari movement

The etymology of the word Rastafari comes from Amharic. Ras Täfäri was the pre-regnal title of Haile Selassie I, composed of the Amharic words Ras (literally “Head”, an Ethiopian title equivalent to duke), and Haile Selassie’s pre-regnal name, Tafari.

Many Rastafarians learn Amharic as a second language, as they consider it to be a sacred language. After Haile Selassie’s 1966 visit to Jamaica, study circles in Amharic were organized in Jamaica as part of the ongoing exploration of Pan-African identity and culture. Various reggae artists in the 1970s, including Ras Michael, Lincoln Thompson and Misty-in-Roots, have sung in Amharic, thus bringing the language to a wider audience. The Abyssinians have also used Amharic most notably in the song Satta Massagana. The title was believed to mean “Give thanks” however this phrase is incorrect. Säţţä means “he gave” and the word amässägänä for “thanks” or “praise” means “he thanked” or “he praised”. The correct way to say “give thanks” in Amharic is one word, misgana. The word “satta” has become a common expression in Rastafari vocabulary meaning “to sit down and partake”.

History

Amhara descendants of ancient Semitic conquerors who migrated southward to mingled with indigenous Cushitic peoples (Oromos) built the powerful ancient Kingdom of Aksum in Ethiopia. They claim ancestry through Shem the eldest son of biblical Noah and trace their lineage all the way to King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba; aw well as the legendary ancient King Menelik I.

There is a record of hunting expeditions by the Ptolemean rulers of Egypt in Ethiopia.

Ptolemy III (245-222 b.c.) placed at the port of Adulis (near present-day Mesewa) a Greek inscription recording that he captured elephants, and an inscribed block of stones with magical hieroglyphs. At the same port about a.d. 60, a Greek merchant named Periplus recorded the importation of iron and the production of spears for hunting elephants, and in a.d. 350 Aeizana, king of Aksum, defeated the Nubians and carried off iron and bronze from Meroë.

The Abyssinian tradition of the Solomonic dynasty, as told in the Ge’ez-language book Kebra Nagast (Honor of the Kings) refers to the rule of Menilek I, about 975-950 b.c. It relates that he was the son of Makeda, conceived from King Solomon during her visit to Jerusalem. Interrupted in a.d. 927 by sovereigns of a Zagwe line, the Solomonic line was restored in 1260 and claimed continuity until Emperor Haile Selassie was deposed in 1974. Abyssinian churches are still built on the principle of Solomon’s temple of Jerusalem, with a Holy of Holies section in the interior. Christianity came to Aksum in the fourth century a.d., when Greek-speaking Syrians converted the royal family. This strain of Christianity retained a number of Old Testament rules, some of which are observed to this day: the consumption of pork is forbidden; circumcision of boys takes place about a week after birth; upper-level priests consider Saturday a day of rest, second only to Sunday; weddings preferably take place on Sunday, so that the presumed deflowering, after nightfall, is considered to have taken place on the eve of Monday. Ecclesiastic rule over Abyssinia was administered early on by the archbishop of Alexandria, detached only after World War II. At the Council of Chalcedon in a.d. 451, the theological Monophysites of Alexandria, including the Abyssinians, had broken away from the European church; hence the designation “Coptic.”

The spread of Islam to regions surrounding it produced relative isolation in Ethiopia from the seventh to the sixteenth centuries. During this period, the Solomonic dynasty was restored in 1260 in the province of Shewa by King Yekuno Amlak, who extended his realm from Abyssinia to some Cuchitic-speaking lands south and east. Amharic developed out of this linguistic blend. From time to time, Europeans heard rumors of a Prester John, a Christian king on the other side of the Muslim world. Using a vast number of serfs on feudal church territories, Abuna (archbishop) Tekle Haymanot built churches and monasteries, often on easily defensible hilltops, such as Debra Líbanos monastery in Shewa, which is still the most important in Ethiopia.

With the Muslim conquest of Somali land in 1430, the ring around Abyssinia was complete, and recently Islamicized Oromo (Galla) seminomadic tribes from the south invaded through the Rift Valley, burning churches and monasteries. Some manuscripts and church paintings had to be hidden on islands on Lake Tana. When a second wave of invaders came, equipped with Turkish firearms, the Shewan king Lebna Dengel sent a young Armenian to Portugal to solicit aid. Before it could arrive, the Oromo leader Mohammed Grañ (“the lefthanded”) attacked with the aid of Arabs from Yemen, Somalis, and Danakils and proceeded as far north as Aksum, which he razed, killing the king in battle in 1540. His children and the clergy took refuge on and north of Lake Tana. One year later, Som Christofo Da Gama landed at Mesewa with 450 Portuguese musketeers; the slain king’s son, Galaudeos (Claudius), fought on until he died in battle. The tide turned, however, and in 1543 Mohammed Grañ fell in battle.

Shewa nevertheless remained settled by Oromo, who learned the agriculture of the region. The royal family had only a tent city in what became the town of Gonder. There the Portuguese built bridges and castles, and Jesuits began to convert the royal family to Roman Christianity. King Za Dengel was the first royal convert, but the Monophysite clergy organized a rebellion that led to his removal. His successor, King Susneos, had also been converted but was careful not to urge his people to convert; shortly before his death in 1632, he proclaimed religious liberty for all his subjects.

Amhara people

The new king, Fasilidas (1632-1667), expelled the Portuguese and restored the privileges of the Monophysite clergy. He—and later his son and grandson—employed workmen trained by the Portuguese to build the castles that stand to this day. Special walled paths shielded the royal family from common sight, but the king, while sitting under a fig tree, judged cases brought before him. A stone-lined water pool was constructed under his balcony, and a mausoleum entombed his favorite horse. All these structures still exist. But the skills of stonemasonry later fell into disuse; warfare required mobility, which necessitated the formation of military tent cities. Portuguese viticulture was also lost (though the name of the middle elevation remains “Woyna Dega”), and the clergy had to import raisins to produce sacramental wine.

Gonder had been abandoned by the Solomonic line when a usurping commoner chieftain, Kassa, chose it as the location to have himself crowned King Theodore in 1855. He defeated the king of Shewa and held the dynastic heir, the boy Menilek II, hostage at his court. Theodore realized the urgency of uniting the many ethnic groups of the country into a nation, to prevent Ethiopia from losing its independence to European colonial powers. Thinking that all Europeans knew how to manufacture cannons, Theodore invited foreign technicians and, at first, even welcomed foreign missionaries. But when the latter proved unable to cast cannons for him and even criticized his often violent behavior, he jailed and chained British missionaries. This led to the Lord Napier expedition, which was welcomed and assisted by the population of Tigray Province. When the fort of Magdalla fell, Theodore committed suicide. A conservative Tigray chief, Yohannes, was crowned at Aksum.

In 1889 the Muslim mahdi took advantage of the disarray in Ethiopia; he razed Gonder and devastated the subprovince of Dembeya, causing a severe and prolonged famine. Meanwhile, the Shewan dynastic heir, Menilek II, had grown to manhood and realized that Ethiopia could no longer isolate itself if it were to retain independence. He proceeded, with patient persistence, to unify the country. As an Amhara from Shewa, he understood his Oromo neighbors and won their loyalty with land grants and military alliances. He negotiated a settlement with the Tigray. He equipped his forces with firearms from whatever source, some even from the Italians (in exchange for granting them territory in Eritrea).

His policies were so successful that he managed to defeat the Italian invasion at Adwa, in 1896, an event that placed Ethiopia on the international map diplomatically. Empress Taitu liked the hot mineral springs of a district in Shewa, even though it was in an Oromo region, and the emperor therefore agreed to build his capital there, naming it “Addis Ababa” (new flower). When expanding Addis Ababa threatened to exhaust the local fuel supply, Menilek ordered the importation of eucalyptus trees from Australia, which grew rapidly during each three-month rainy season.

Menilek II died in 1913, and his daughter Zauditu became nominal head; a second cousin, Ras Tafari Makonnen, became regent and was crowned King of Kings Haile Selassie I in 1930. He made it possible for Ethiopia to join the League of Nations in 1923, by outlawing the slave trade. One of his first acts as emperor was to grant his subjects a written constitution. He allied himself by marriage to the Oromo king of Welo Province. When Mussolini invaded Ethiopia in 1935, Emperor Haile Selassie appeared in Geneva to plead his case before the League, warning that his country would not be the last victim of aggression. The Italian occupation ended in 1941 with surrender to the British and return of the emperor. During succeeding decades, the emperor promoted an educated elite and sought assistance from the United States, rather than the British, in various fields. Beginning in about 1960, a young, educated generation of Ethiopians grew increasingly impatient with the slowness of development, especially in the political sphere. At the same time, the aging emperor, who was suffering memory loss, was losing his ability to maintain control. In 1974 he was deposed, and he died a year later. The revolutionary committees, claiming to follow a Marxist ideology, formed military dictatorships that deported villagers under conditions of great suffering and executed students and each other without legal trials. Dictator Mengistu Haile Mariam fled Ethiopia in May 1991 as Eritrean and Tigrayan rebel armies approached from the north. The country remains largely rural; traditional culture patterns and means of survival are the norm.

Settlements

The typical rural settlement is the hamlet, tis, called mender if several are linked on one large hill. The hamlet may consist of two to a dozen huts. Thus, the hamlet is often little more than an isolated or semi-isolated farmstead, and another hamlet may be close by if their plowed fields are near. Four factors appear to determine where a hamlet is likely to be situated: ecological considerations, such as water within a woman’s walking distance, or available pasturage for the flock; kinship considerations—persons within a hamlet are nearly always related and form a family economic community; administrative considerations, such as inherited family ownership of land, tenancy of land belonging to a feudal lord of former times, or continuing agreement with the nearby church that had held the land as a fief up to 1975 and continues to receive part of the crop in exchange for its services; and ethnic considerations. A hamlet may be entirely inhabited by Falasha blacksmiths and pottery makers or Faqi tanners. Most of the Falasha have now left Ethiopia.

To avoid being flooded during the rainy season, settlements are typically built on or near hilltops. There is usually a valley in between, where brooks or irrigation canals form the border for planted fields. The hillsides, if not terrace farmed, serve as pasturage for all hamlets on the hill. Not only sheep and goats, but also cows, climb over fairly steep, bushy hillsides to feed. Carrying water and branches for fuel is still considered a woman’s job, and she may have to climb for several hours from the nearest year-round water supply. The hamlet is usually patrilocal and patrilineal. When marriage occurs, usually early in life, a son may receive use of part of his father’s rented (or owned) field and build his hut nearby. If no land is available owing to fragmentation, the son may reluctantly be compelled to establish himself at the bride’s hamlet. When warfare has killed off the adult males in a hamlet, in-laws may also be able to move in. Some hamlets are fenced in by thorn bushes against night-roving hyenas and to corral cattle. Calves and the family mule may be taken into the living hut at night. There is usually at least one fierce reddish-brown dog in each hamlet.

Economy

Much Amhara ingenuity has long been invested in the direct exploitation of natural resources. An Amhara would rather spend as much time as necessary searching for suitably shaped hard or soft saplings for a walking cane than perform carpentry, which is traditionally largely limited to constructing the master bed (alga ), wooden saddles, and simple musical instruments. Soap is obtained by crushing the fruit of the endod (Pircunia abyssinica ) bush. Tannin for depilation of hides and curing is obtained from the yellow fruit of the embway bush. Butter is preserved and perfumed by boiling it with the leaves of the odes (myrtle) bush. In times of crop failure, edible oil is obtained by gathering and crushing wild-growing sunflower seeds (Carthamus tinctorus ). If necessary, leaves of the lola bush can be split by women to bake the festive bread dabbo. The honey of a small, tiny-stingered bee (Apis dorsata ) is gathered to produce alcoholic mead, tej, whereas the honey of the wild bee tazemma (Apis Africans miaia ) is gathered to treat colds and heart ailments. Fishing is mostly limited to the three-month rainy season, when rivers are full and the water is muddy from runoff so that the fish cannot see the fishers. Hunting elephants used to be a sport of young feudal nobles, but hunting for ivory took place largely in non-Amhara regions. Since rifles became available in Amhara farming regions, Ethiopian duikers and guinea fowl have nearly disappeared.

Subsistence farming provides the main economy for most rural Amhara. The traditional method required much land to lie fallow because no fertilization was applied. Cattle manure is formed into flat cakes, sun dried, and used as fuel for cooking. New land, if available, is cleared by the slash-and-burn method. A wooden scratch plow with a pointed iron tip, pulled by oxen, is the main farming tool. Insecurity of land tenure has long been a major factor in discouraging Amhara farmers from producing more than the amount required for subsistence. The sharecropping peasant (gabbar ) was little more than a serf who feared the (often absentee) feudal landlord or military quartering that would absorb any surplus. The revolutionary government (1975-1991) added additional fears by its villagization program, moving peasants at command to facilitate state control and deporting peasants to the south of Ethiopia, where many perished owing to poor government planning and support.

The preferred crop of the Amhara is tyeff (Eragrostis abyssinica; Poa abyssinica ), the small seeds of which are rich in iron. At lower or drier elevations, several sorghums (durras) are grown: mashella (Andropogon sorghum), often mixed with the costlier tyeff flower to bake the flapjack bread injera; zengada (Eleusina multiforme), grown as crop insurance; and dagussa (Eleusine coracana, or tocusso ), used as an ingredient in beer together with barley. Wheat (Triticum spp.), sendē, is grown in higher elevations and is considered a luxury. Barley (Hordeum spp.), gebs, is a year-round crop, used primarily for brewing talla, a mild beer, or to pop a parched grain, gebs qolo, a ready snack kept available for guests. Maize, bahēr mashella, is recognized as a foreign-introduced crop.

Amhara farmers

The most important vegetable oil derives from nug (Guizotia abyssinica ), the black Niger seed, and from talba (Linum usitatissimum ), flax seed. Cabbage (gomen ) is regarded as a poor food. Chick-peas are appreciated as a staple that is not expected to fail even in war and famine; they are consumed during the Lenten season, as are peas. Onions and garlic are grown as ingredients for wot, the spicy stew that also contains beans, may include chicken, and always features spicy red peppers—unless ill heath prevents their consumption. Lentils substitute for meat during fasting periods. The raising of livestock is traditionally not directly related to available pasture, but to agriculture and the desire for prestige. Oxen are needed to pull the plow, but traditionally there was no breeding to obtain good milkers. Coffee may grow wild, but the beans are usually bought at a market and crushed and boiled in front of guests; salt—but not sugar—may be added.

Division of Labor

Although much needed, the castelike skilled occupations like blacksmithing, pottery making, and tanning are held in low esteem and, in rural regions, are usually associated with a socially excluded ethnic grouping. Moreover, ethnic workmanship is suspected of having been acquired by dealings with evil spirits that enable the artisans to turn themselves into hyenas at night to consume corpses, cause diseases by staring, and turn humans into donkeys to utilize their labor.

Such false accusations can be very serious. On the other hand, the magic power accredited to these workers is believed to make their products strong, whereas those manufactured by an outsider who might have learned the trade would soon break. The trade of weaving is not afflicted by such suspicions, although it is sometimes associated with Muslims or migrants from the south.

Land Tenure

Land tenure among traditional rural Amhara resembled that of medieval Europe more than that found elsewhere in Africa. Feudal institutions required the gabbar to perform labor (hudād ) for his lord and allocated land use in exchange for military service, gult. In a system resembling the European entail, inheritable land, rest, was subject to taxation (which could be passed on to the sharecroppers) and to expropriation in case of rebellion against the king. Over the centuries, endowed land was added to fief-holding church land, and debber ager. Royal household lands were classified as mād-bet, and melkenya land was granted to tax collectors. Emperor Haile Selassie attempted to change the feudal system early in his administration. He defeated feudal armies, but was stymied in abrogating feudalistic land tenure, especially in the Amhara region, by feudal lords such as Ras Kassa. The parliament that he had called into existence had no real power All remaining feudal land tenure was abrogated during the revolutionary dictatorship (1975-1991), but feudalistic attitudes practiced by rural officials, such as shum shir (frequently moving lower officials to other positions to maintain control), appear to have persisted.

Kinship

The extended patrilocal, patrilineal, patriarchal family is particularly strong among holders of rest land tenure, but is found, in principle, even on the hamlet level of sharecroppers. There are several levels of kin, zemed, which also include those by affinity, amachenet. In view of the emphasis on seeking security in kinship relations, there are also several formal methods of establishing fictive kinship, zemed hone, provided the person to be adopted is attentam (“of good bones,” i.e., not of Shanqalla slave ancestry). Full adoption provides a breast father (yetut abbat ) or a breast mother (yetut ennat ). The traditional public ceremony included coating the nipples with honey and simulating breast-feeding, even if the child was already in adolescence.

Marriage and Family

Marriage. There are three predominant types of marriage in Amhara tradition. The three types of marriage in Amhara tradition:

Eucharist church marriage (Qurban)

Kin-negotiated civil marriage (Semanya) and

Temporary marriage (Damoz)

Only a minority—the priesthood, some older persons, and nobility—engage in eucharistic church marriage (qurban ). No divorce is possible. Widows and widowers may remarry, except for priests, who are instead expected to become monks.

Kin-negotiated civil marriage (semanya; lit., “eighty”) is most common. (Violation of the oath of marriage used to be penalized by a fine of 80 Maria Theresa thalers.) No church ceremony is involved, but a priest may be present at the wedding to bless the couple. Divorce, which involves the division of property and determination of custody of children, can be negotiated. Temporary marriage (damoz ) obliges the husband to pay housekeeper’s wages for a period stated in advance. This was felt to be an essential arrangement in an economy where restaurant and hotel services were not available.

The term is a contraction of demewez, “blood and sweat” (compensation). The contract, although oral, was before witnesses and was therefore enforceable by court order. The wife had no right of inheritance, but if children were conceived during the contract period, they could make a claim for part of the father’s property, should he die. Damoz rights were even recognized in modern law during the rule of Emperor Haile Selassie.

Socialization in the domestic unit begins with the naming of the baby (giving him or her the “world name”), a privilege that usually belongs to the mother. She may base it on her predominant emotion at the time (e.g., Desta [joy] or Almaz [diamond]), on a significant event occurring at the time, or on a special wish she may have for the personality or future of her baby (Seyum, “to be appointed to dignity”).

Amhara school kids

Socialization

Breast-feeding may last two years, during which the nursling is never out of touch with the body of the mother or another woman. Until they are weaned, at about age 7, children are treated with permissiveness, in contrast to the authoritarian training that is to follow. The state of reason and incipient discipline begins gradually at about age 5 for girls and 7 for boys. The former assist their mothers in watching babies and fetching wood; boys take sheep and cows to pasture and, with slingshots, guard crops against birds and baboons. Both can be questioned in court to express preferences concerning guardianship in case of their parents’ divorce. Neglect of duty is punished by immediate scolding and beating.

Formal education in the traditional rural church school rarely began before age 11 for boys. Hazing patterns to test courage are common among boys as they grow up, both physically and verbally. Girls are enculturated to appear shy, but may play house with boys prior to adolescence. Adolescence is the beginning of stricter obedience for both sexes, compensated by pride in being assigned greater responsibilities. Young men are addressed as ashker and do most of the plowing; by age 18 they may be addressed as gobez, signifying (strong, handsome) young warrior. On the Temqet (baptism of Jesus) festival, the young men encounter each other in teams to compete in the game of guks, a tournament fought on horseback with blunt, wooden lances, in which injuries are avoided by ducking or protecting oneself with leather shields. At Christmas, a hockeylike game called genna is played and celebrated by boasting (fukkara ). Female adolescents are addressed as qonjo (beautiful), no longer as leja-gered (servant maid), unless criticized. Singing loudly in groups while gathering firewood attracts groups of young men, away from parental supervision. Young men and women also meet following the guks and genna games, wearing new clothes and traditional makeup and hairstyles. Outdoor flirting reaches a peak on Easter (Fassika), at the end of the dry season.

Domestic Unit

The traditional age of a girl at first marriage may be as young as 14, to protect her virginity, and to enable the groom to tame her more easily. A groom three to five years older than the bride is preferred. To protect the bride against excessive violence, she is assigned two best men, who wait behind a curtain as the marriage is consummated; later, she may call on them in case of batter.

The term shemagelyē signifies an elder and connotes seriousness, wisdom, and command of human relations within the residential kin group or beyond. He may be 40 years of age and already a grandfather. There is no automatic equivalency for elder women, but they can take the qob of a nun and continue to live at home while working in the churchyard, baking bread and brewing beer for the priests. Only women past menopause, usually widows, are accepted as nuns by the Monophysite Aybssinian church. Younger women are not considered sufficiently serious to be able to deny their sex drives.

Inheritance patterns:

Though the authority of the household head is thus relatively independent of kinship ties, the land-use rights on which the household as an economic unit relies are not, for plots of land and potential rights to additional plots are inherited bilaterally—that is, by sons and daughters (or their husbands or children) through both parents.

Amhara elders

In Amhara theory these actual and potential rights, both of which are termed rist, are rights to a share of the land first held by an illustrious ancestor (a principal ancestor or wanna abbat ) whose name the land still bears. The arable lands in older Amhara regions are these ancestral blocks, which vary from one half to two or three square kilometers in area. In Amhara legal theory rist rights in these lands are the inalienable and inextinguishable birthright of all the first ancestor’s descendant’s in all lines, regardless of whether or not the rights were utilized by intermediate lineal ancestors in the claimant’s pedigree. In fact, most claims are forgotten.

Though rist land rights are “hereditary,” the amount of land a man can control by virtue of these rights is dependent, above all, on his political influence; and land use rights over plots are considered to be held by individuals.

Sociopolitical Organization

Social organization is linked to land tenure of kinfolk, feudalistic traditions and the church, ethnic division of labor, gender, and age status. The peasant class is divided between landowning farmers, who, even though they have no formal political power, can thwart distant government power by their rural remoteness, poor roads, and weight of numbers, and the sharecroppers, who have no such power against local landlords. Fear of a person who engages in a skilled occupation, tebib (lit., “the knowing one,” to whom supernatural secrets are revealed), enters into class stratification, especially for blacksmiths, pottery makers, and tanners. They are despised as members of a lower caste, but their products are needed, and therefore they are tolerated. Below them on the social scale are the descendants of slaves who used to be imported from the negroid Shanqalla of the Sudanese border, or the Nilotic Barya, so that both terms became synonymous with “slave.”

Social control is traditionally maintained, and conflict situations are resolved, in accordance with the power hierarchy. Judges interpret laws subjectively and make no sharp distinction between civil and criminal procedures. In addition to written Abyssinian and church laws, there are unwritten codes, such as the payment of blood money to the kin of a murder victim. An aggrieved person could appeal to a higher authority by lying prostrate in his path and shouting “abyet” (hear me). Contracts did not have to be written, provided there were reliable witnesses. To obtain a loan or a job, a personal guarantor (was ) is necessary, and the was can also act as bondsman to keep an accused out of jail. The drama of litigation, to talk well in court, is much appreciated. Even children enact it with the proper body language of pointing a toga at the judge to emphasize the speech.

Religious Belief

The religious belief of most Amhara is Monophysite–that is, Tewahedo (Orthodox)–Christianity, to such an extent that the term “Amhara” is used synonymously with “Abyssinian Christian.” Christian Amhara wear a blue neck cord (METEB), to distinguish themselves from Muslims.

There are essentially four separate realms of supernatural beliefs.

Ethiopian Church priest and his censer. (Timkat ceremony) at northern Ethiopia

First, there is the dominant Monophysite Christian religion involving the Almighty God, the Devil, and the saints and angels in Heaven. Second, there are the zar and the adbar spirits, “protectors” who exact tribute in return for physical and emotional security and who deal out punishments for failure to recognize them through the practice of the appropriate rituals. Third is the belief in the buda, a class of people who possess the evil eye, and who exert a deadly power over the descendents of God’s “chosen children.” The fourth category of beliefs includes the [unknown]ciraq and satan, ghouls and devils that prowl the countryside, creating danger to unsuspecting persons who cross their path.

A second important influence in the development of Amhara culture was heralded by the introduction of Christianity during the fourth century. These first missionaries were men from the eastern Mediterranean and, after the great schism announced at Chalcedon, the Ethiopian Church continued its ties with the Orthodox faction, as a dependency of the Coptic See of Alexandria. The success of Islam, sweeping across Egypt and Nubia, severely limited contact between the Abyssinian highland and the rest of Christendom. In consequence, the development of the Ethiopian Coptic Church and, ultimately, of its relationship to Amhara culture has been more substantially influenced by autochthonous forces than would otherwise have been the case.

The influence of the Church is nowhere more apparent than in a review of Amhara art. The Amhara have no concept which approximates “art” as it is used in English, and each of the varieties of Amhara graphic art—Church painting, occult drawing, and tattooing—is considered discrete, a distinctive instrument to achieve particular ends. Painting, for example, is largely didactic, depicting biblical scenes and personages, episodes from the lives of the saints and the history of the Church. In a style of obvious Byzantine affinity, the painter sets these motifs in contiguous panels upon the muslin-faced walls and ceilings of highland churches.

The mystical drawing is known in Amharic as telsem (cognate of the English “talisman”) and differs radically from the church painting in form, intent, and production. Ethiopian talismans, sewn into a leather amulet together with the appropriate herbal ingredients, are worn to ward off the numerous satans, persecutors of man and foes of the Church, who live in the forests, lakes, and rivers of the countryside and in the hearth ashes and beer dregs of the home. Both the church painter and talisman drawer are ecclesiastics, since a religious education is the sole means of acquiring the literacy and special knowledge required by these endeavors. Indeed, the paintings and drawings accompanying this article are the work of a single individual who lives in Gondar town (about thirty miles north of Lake Tana), national capital during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Amhara people

Ceremonies

Ceremonies often mark the annual cycle for the public, despite the sacredotal emphasis of the religion. The calendar of Abyssinia is Julian, but the year begins on 11 September, following ancient Egyptian usage, and is called amete mehrāt (year of grace). Thus, the Abyssinian year 1948 a.m. corresponds roughly with the Gregorian (Western) a.d. 1956.

The new year begins with the month of Meskerem, which follows the rainy season and is named after the first religious holy day of the year, Mesqel-abeba, celebrating the Feast of the Cross. On the seventeenth day, huge poles are stacked up for the bonfire in the evening, with much public parading, dancing, and feasting. By contrast, Christmas (Ledet) has little social significance except for the genna game of the young men. Far more important is Epiphany (Temqet), on the eleventh day of Ter. Ceremonial parades escort the priests who carry the tabot, symbolic of the holy ark, on their heads, to a water pool. There are all-night services, public feasting, and prayers for plentiful rains.

This is the end of the genna season and the beginning of the guks tournaments fought on horseback by the young men. The long Lenten season is approaching, and clergy as well as the public look forward to the feasting at Easter (Fassika), on the seventeenth day of Miyazya. Children receive new clothes and collect gifts, chanting house to house. Even the voluntary fraternal association mehabber is said to have originated from the practice of private communion. Members take turns as hosts at monthly meetings, drinking barley beer together with the confessor-priest, who intones prayers. Members are expected to act as a mutual aid society, raising regular contributions, extending loans, even paying for the tazkar (formal memorial service) forty days after a member’s death, if his family cannot afford it.

Passage rituals (birth, death, puberty, seasonal):

When death is approaching, elder kin of the dying person bring the confessor, and the last will concerning inheritance is pronounced. Fields are given to patrilineal descendants, cattle to all offspring. Personal belongings, such as ox hide mats and a SHAMMA (toga), may be given to the confessor, who administers last rites and assigns a burial place in the churchyard.

The corpse is washed, wrapped in a SHAMMA, carried to church for the mass, and buried, traditionally without a marker except for a circle of rocks. Women express grief with loud keening and wailing. This is repeated when kinfolk arrive to console the relatives of the deceased. A memorial feast (TAZKAR) is held forty days after death, when the soul has the earliest opportunity to be freed from purgatory. Preparations for this feast begin at the time of the funeral: money is provided for the priest to recite the FETET, the prayer for absolution, and materials, food, and drink are accumulated. It is often the greatest single economic expenditure of an individual’s lifetime and, hence, a major social event. For the feasting, a large, rectangular shelter (DASS) is erected, and even distant kin are expected to participate and consume as much TALLA and WOT as available.

Clothing/Costume

Whether it is at a church service or at court, on the trail or in the privacy of the homestead, decorous and elaborate forms of speech, dress, and gesture are employed by the Amhara to express toward one another appropriate degrees of subordination and superordination. In virtually all of these situations it is possible (with adequate knowledge) to discern a pattern of ranking, an ordered difference in the amount of deference that people give and receive. An accidental or transitional lapse in this orientation causes the Amhara discomfort or embarrassment. There is a moment of confusion or deliberate “not noticing” while people rearrange their positioning and their clothing so as to satisfactorily reorder the scene with regard to the main sources of secular or sacred authority.

Food

The Amhara like other Ethiopian staple foods are mainly their grains, which are Tef, Barley, and Emmer Wheat. Grains are grinded in the home or in a local mill, with the latter option being more and more common. These grains are made into a bread called injera. Injera is a thin, pancake-like, sour, leavened bread. Which grain is used depends on which is the main crop in a specific area. Injera has been made by the people of Ethiopia since at least 100 B.C. This bread is usually accompanied by a sauce called wot. Some common types of wat are geyy wat, dorro wat and allicha wat. Pictured below is Doro Wat. This is the national dish of Ethiopia.

Food items of plant origin are cereals, legumes, vegetables, tubers, spices, oilseeds, and fruit. Cereals consist of teff, corn, sorghum, barley wheat and millet. The most common legumes are chickpeas, field peas, lentils, and broad beans. The most common vegetables are onions, kale, pumpkins, and green chickpeas. The most common tubers are potatoes, sweet potatoes, galla potatoes. Spices are extremely important and the most important are chili and bird’s-eye chili. These spices are used in the spice mixtures berberre and mitmitta. Additionally the oilseeds of niger flax, sunflowers, and safflowers are and important cash crop and fruit is not grown in large quantities. The most common fruits are lemons and bananas.

Gondar, Amhara Region, Ethiopia: injera with meat – Ethiopian food

Food items of animal origin consist of milk, cow, sheep, or goat, chicken, fish. Ethiopian people do not consume pork. Milk is mainly given to small children and it is used to make sour milk, butter and low-fat sour-milk cheese. The wealthy class can afford meats but the majority of the population only can serve meat at ceremonial occasions.

In addition, Coffee is another food staple in Ethiopia. Drinking coffee is the most important social function among the women in a village and in some institutions. Women should not be disturbed during their coffee drinking hours. Coffee is usually served with a small snack, such as toasted cereals, legumes, or a piece injera. The beverage for weekdays is the local beer called tella and for feasts it is honey wine called tejj. It is considered polite to serve a beverage glass so full that it overflows, and also to serve a second glass as soon as the first is finished.

The Ethiopian Orthodox Christians participate in fasts. The fasting rules dictate that food should not include any animal origin, with the exception of fish. Therefore, the main ingredient in the wot has to be of vegetable origin. Fish is generally too expensive for the majority of people in Ethiopia; therefore they eat food mainly based of vegetable origins.

Adornment (beads, feathers, lip plates, etc.):

Many designs are specific for body area and ailment; the zigzag, for example, customarily appears as multiple necklaces and is directed against goiter. Other patterns may be inscribed on several areas; circles and crucifixes appear on forehead and temples to prevent recurrent headaches, on the forearm for muscle paralysis, and at joints for rheumatism.

The effectiveness of the designs is by means of an unknown modus vivendi, and innovation is discouraged on this account. Cosmetic and medical motives are frequently difficult to distinguish from one another: Prophylactic and therapeutic tattoos on face and throat are often regarded as fortuitously enhancing the bearer’s beauty.

Similarly, essentially decorative tattooing is sometimes given a secondary, prophylactic, rationale; the “beaded ankle” motif, for example, is believed to attract the witch’s evil eye away from the vulnerable mouth area.

Arts

Verbal arts—such as bedanya fit (speaking well before a judge)—are highly esteemed in general Amhara culture, but there is a pronounced class distinction between the speech of the rustic peasant, balager (hence belegē, unpolished, sometimes even vulgar), and chowa lij, upper-class speech. A further differentiation within the latter is the speech of those whose traditional education has included sewassow (Ge’ez: grammar; lit., “ladder,” “uplifting”), which is fully mastered mainly by church scholars; the speeches of former emperor Haile Selassie, who had also mastered sewas-sow, impressed the average layperson as esoteric and hard to understand, and therefore all the more to be respected. In the arts of politeness, veiled mockery, puns with double meanings, such as semmena-worq (wax and gold), even partial knowledge of grammar is an advantage. The draping of the toga (shamma) is used at court and other occasions to emphasize spoken words, or to communicate even without speech. It is draped differently to express social status in deference to a person of high status, on different occasions, and even to express moods ranging from outgoing and expansive to calm sobriety, to sadness, reserve, pride, social distance, desperate pleading, religious devotion, and so on. Artistic expression in the fine arts had long been linked to the church, as in paintings, and sponsorship by feudal lords who could afford it, especially when giving feasts celebrated with a variety of musical instruments.

Medicine.

Many men consider the zar cult effeminate and consult its doctors by stealth only, at night. Husbands may resent the financial outlays if their wives are patients, but fear the wives’ relapse into hysterical or catatonic states. Women, whose participation in the Abyssinian church is severely limited, find expression in the zar cult. The zar doctors at Gonder hold their annual convention on the twenty-third night of the month of Yekatit, just before the beginning of the Monophysite Christian Lent (Kudade; lit., “suffering”). There is much chanting, dancing, drumming, and consumption of various drinks at the love feasts of the zars. Poor patients who are unable to pay with money or commodities can work off their debts in labor service to the cult—waitressing, weaving baskets, fetching water and fuel, brewing barley beer, and so forth. They are generally analyzed by the zar doctor as being possessed by a low-status zar spirit.

By contrast, possession by an evil spirit (buda ) is considered more serious and less manageable than possession by a zar, and there is no cult. An effort is made to prevent it by wearing amulets and avoiding tebib persons, who are skilled in trades like blacksmithing and pottery making. Since these spirits are believed to strike beautiful or successful persons, such individuals—especially if they are children—must not be praised out loud. If a person sickens and wastes away, an exorcism by the church may be attempted, or a tanqway (divinersorcerer) may be consulted; however, the latter recourse is considered risky and shameful.

Death and Afterlife

When an elder is near death, other elders from his kin group bring the confessor and say to him, “Confess yourself.” Then they ask him for his last will—what to leave to his children and what for his soul (the church). The confessor gives last rites and, after death, assigns a burial place in the churchyard. The corpse is washed, wrapped in a shamma, carried to church for the mass, and buried, traditionally without a marker except for a circle of rocks. Women express grief with loud keening and wailing. This is repeated when kinfolk arrive to console. A memorial feast (tazkar) is held forty days after the death of a man or a woman, when the soul has the earliest opportunity to be freed from purgatory. Preparations for this feast begin at the time of the funeral: money is provided for the priest to recite the fetet, the prayer for absolution, and materials, food, and drink are accumulated. It is often the greatest single economic expenditure of an individual’s lifetime and, hence, a major social event. For the feasting, a large, rectangular shelter (dass ) is erected, and even distant kin are expected to participate and consume as much talla and wot as available.

Source:http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Amhara.aspx

A BRIEF NOTE ON THE ORIGIN OF THE AMARA AND OROMO

By Fikre Tolossa

I gave my word last night to Ato Zewge Fanta and Wondimu Mekonnen that I would provide briefly the genealogy of the Amara. This information is based on on my reading of Ethiopian history and Metsehafe Djan Shewa, (an ancient Ethiopian manuscript in Geez discovered by Meri Ras Aman Belay, in the ruins of an Ethiopian church in Nubia, a part of the Ethiopian Empire) which has been, translated into Amharic, abridged and published as Metsehafe Subae by the discoverer himself. According to this ancient manuscript, both the Amara and the Oromo are the descendants of one man or father- Melchizedek, King of Salem the highest priest of God on Earth, founder of Jerusalem to whom Abraham and other kings bowed and paid tithes to receive his blessings.

About 2000 years before the birth of Jesus Christ, God ordered Melchizedek to send his son Ethel who was named as Ethiop later on by God, to go and settle in Ethiopia at the islands of Lake Tana, the source of the River Nile. God sent Ethel (meaning the gift of God) to Ethiopia, so that when God (Jesus Christ) is born as a human being 2000 years later, the descendants of Ethel would bring him to Bethlehem Ethiopian gifts such as yellow gold, myrrh and incense, led by a star which would appear in Ethiopia to lead them to Bethlehem. Accordingly Ethel went to Ethiopia and settled in what is today known as Gojjam. God changed his name from Ethel to “Ethiop” meaning “the gift of yellow gold to God”. Thus, not only Ethel became Ethiop, but the land in which he settled also started to be called “Ethiopia”. Lo and behold, 2000 years later, the descendants of Ethiop became 12 kings in the then Ethiopian Empire. They headed for Bethlehem with gifts led by the star which God had said would lead them. Now Ethiop begat 13 children- ten boys and three girls. The boys were: Atiba, Bior, Biora, Temna, Ater, Ashan, Azib, Berissa, Tesbi, Tola (by the way, the name of my uncle, the brother of my father Tolossa, was Tola.), and Azeb. The girls were, Loza, Milka and Suba. All of them became the fathers and mothers of many, many Ethiopian tribes. Out of the ten boys of Ethiop, I will take only the line of one of them- the line of Bior and show that the Amara and Oromo descend from him. Ethiop begat Bior, Bior begat Aram, Aram begat Nage who begat Hage, who begat Biora, who begat Belam (a prophet in the Sinai who prophesied the Birth of Jesus as a Star.

He is in the Bible known as Baalam), Belam begat Keramid, who begat Shemshel (a female, great prophetess who was able to raise the dead). Shemshel begat Deshet. Her son Deshet too, became a major prophet who designed the Zodiac which was taken out of Ethiopia and did spread elsewhere in the world. Deshet, while meditating at the Bank of the River Nile about 15 hundred years before the birth of Jesus Christ saw in the foam of the River a vision of Mary, Jesus and the Star, that would lead his descendants to Bethlehem, and drew them on a tablet and passed the tablet to them. Now Deshet begat four sons who became the fathers of many Ethiopian tribes including the Amara and the Oromo. They are: Maji, Jimma, Mendi and Medebai. Maji begat Mara (Amara) and Jema or Jama (the people who settled at the River Jema in today’s Shoa, a river they named after their tribe. The Jamacans of Jamaica were captured by Ahmed Gragn when they fought him fiercely, taken from there, sold as slaves to Arabs who sold them to European slave traders, who sold them in Jamaica). Jimma begat Geneti, Arerti and Moren. Out of Medebay descended the Oromo. In fact, before the Oromo were called Oromo during the reign of Menelik I about 2950 years ago, they used to be called Medebay. There are some in Ethiopia who are still called Medebay retaining their original name. There is a reason why they started being called “Gala” and “Oromo” then, but I won’t dwell on it now. Later on, the children of Mara began to be called “A-mara” or “Ha-mara”. The words, “A” and “Ha” were used as indicators. Thus the Oromo and Amara share the same father and grand father. It is tragic and unfortunate that the Oromo and the Amara have been misled to fight each other in the past and in our time. Both the Oromo and Amara originated in Gojjam. The Oromo didn’t come from Asia or Madagascar, as Aleka Taye and other ill-informed historians suggest. Later, each tribe split and spread all over the breath and length of Ethiopia and even the rest of Africa to seek out their fortune. In the mean time, they developed different languages and cultures. The Oromo became pastoralists. The Amara specialized in warfare and administration. For example, when Axumite was a little boy he was crowned as the Pharaoh of Egypt by the name of Ramzes. It was the Amara who accompanied him all the way from Ethiopia to Egypt about 2850 years ago to protect his throne. About 350,000 Amaras went with him to Egypt. Some of them returned to Ethiopia only after 1850 years of stay in Egypt, accompanying King Lalibela to Ethiopia after his return from exile in Jerusalem. They built together with the local Agew people, the Rock Hewen Churches of Lalibela. Later, when Axumite found the city of Axum and became Emperor of Ethiopia, he gave his daughter Ribla in marriage to King Nabukedenesor of Babylon (today’s Iraq). It was the Amara soldiers again who accompanied Ribla to Iraq. She found a city after her name. The Amara found a city called “Amara” in Iraq after their own name. The city of “Amara” exists to this day in Iraq. It was captured by Shiite Moslems about a year ago. I have an American newspaper in my possession which printed the capture of the city of “Amara” by the Shiites. Pertaining to the Amara language, it had already begun to evolve as far back as 3000 years ago.In fact, it had existed long before Geez. Menelik the I declared Geez as the official language of Ethiopia about 2950 years ago to honor and empower the Agazi, a tribe he brought from Gaaza which fought for him when Ethiopian tribes warred against him treating him as a Jewish “keles” who had ambition over the Ethiopian throne. Indeed, it had developed and evolved more than 3000 years; i.e, a while before Geez was decreed by Menelik I as the official language of Ethiopia by imposition. For instance, there are kings and throne names that have Amara names such as Zerffe and Sendek-alma in the list of Ethiopian kings who reigned before Queen Sheba, mother of Menelik I; as well ancient towns in Egypt known as Amarna (konjo honin) and Delta (we are comfortable, we are doing fine), in the region in which Jesus, Joseph and Mary found refuge 2000 years ago. When Menelik I was born, the Amara wondered what King Solomon would say about his son, Menelik, and called him “Menelik” (min yilik, abateh?). If the Amara language didn’t exist over 3000 years ago, how come they called Menelik, “Minyilik” about 3000 years ago? I think this word alone suffices to prove that Amaregna and the Amara had existed in Ethiopia more than 3000 years ago. This is what I wanted to say for now. If I find time, I will detail all this in an article. I have gathered all the literature that I need to prove my point. I am Fikre Tolossa, descendant of Melchitsedek, King of Salem, of Ethiop and Deshet, the prophet, as, of course, all of you, my fellow Ethiopians,

source:http://fikretolossa.com/FILES_ARCHIVE/MISCELANEOUS/A_BRIEF_NOTE_ON_THE_ORIGIN_OF_THE_AMARA_AND_OROMO[1]_2.pdf

The Evil Eye Belief Among the Amhara of Ethiopia

Ronald A Reminick

Cleveland State University

Variations of the belief in the evil eye are known throughout much of the world, yet surprisingly little attention has been given to explaining the dynamics of this aspect of culture ( cf. SpoonerI9 70; FosterI 972; Douglas I970). The Amhara of Ethiopia hold to this belief. Data for this study

were gathered among the Manze Amhara of the central highlands of Shoa Province, Ethiopia. Their habitat is a rolling plateau ranging in altitude from 9,500 to I3,000 feet. The seasons vary from temperate and dry to wet and cold. The Amhara are settled agriculturists raising primarily barley,

wheat, and a variety of beans and importing teff grain cotton, and spices from the lower and warmer regions in the gorges and valleys nearby. Amhara technology is simple, involving the bull draw plow, crop rotation, soil furrowing for drainage and some irrigation where streams are accessible. The soil is rich enough to maintain three harvests annually. Other important technological items include the sickle loom, and the walking and fighting stick for the men; the spindle large clay water jug grindstone, and cooking u tensilsf or the women. The most highly prized item of technology is the ride which symbolizes the proud warrior traditions of the Amhara and a man’s duty to defend his inherited land.