Aklog Birara, PhD

December 09. 2020

Abstract

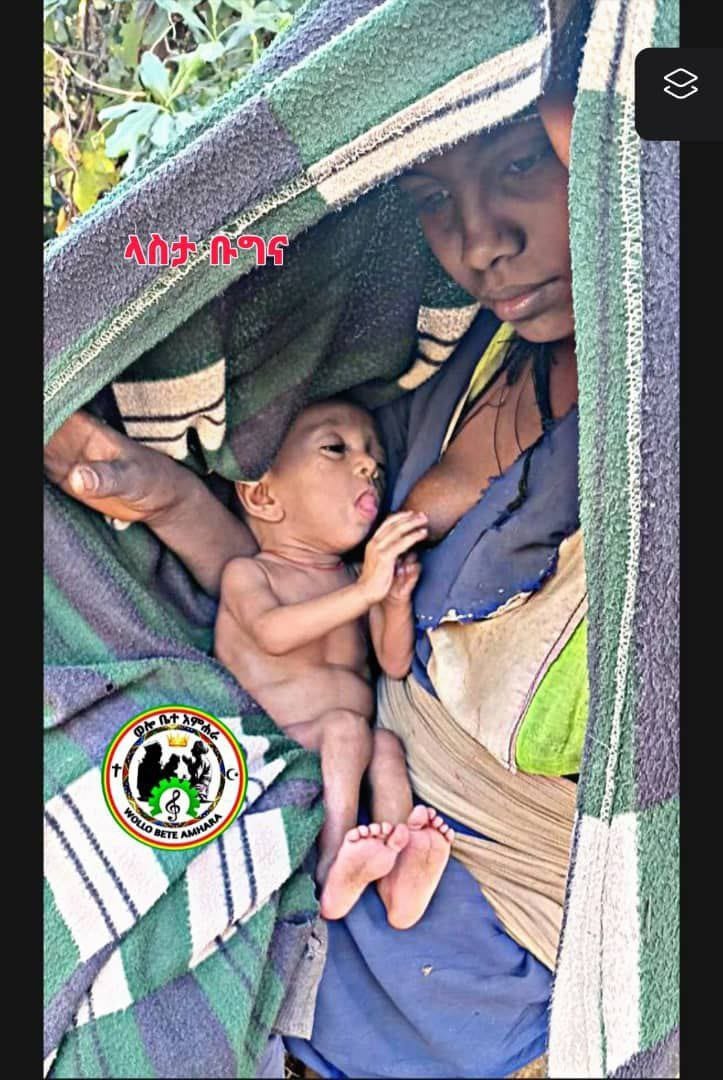

Sub-Saharan Africa is full of promise. It has immense untapped natural resources and a growing human capital base, mostly young. Its immense potential is constrained by poor governance, rent seeking, and massive illicit outflow of capital, tribal conflicts, and terrorism. Ethiopia represents Africa’s promise and pitfalls. Recent events in Oromia show that the country is poorly governed. I do not dispute growth in social and physical infrastructure fueled largely by foreign aid, Foreign Direct Investment, and remittances. Aid contributes 50 to 60 percent of government budget. Social development indices show that Ethiopia is among the most repressed and poorest nations in the world. It is experiencing the worst famine in 30 years with an estimated 18 million people requiring food aid.

Sub-Saharan Africa is full of promise. It has immense untapped natural resources and a growing human capital base, mostly young. Its immense potential is constrained by poor governance, rent seeking, and massive illicit outflow of capital, tribal conflicts, and terrorism. Ethiopia represents Africa’s promise and pitfalls. Recent events in Oromia show that the country is poorly governed. I do not dispute growth in social and physical infrastructure fueled largely by foreign aid, Foreign Direct Investment, and remittances. Aid contributes 50 to 60 percent of government budget. Social development indices show that Ethiopia is among the most repressed and poorest nations in the world. It is experiencing the worst famine in 30 years with an estimated 18 million people requiring food aid.

Ethiopia is the largest recipient of Western aid in Sub-Saharan Africa. It is part of the globalization process. My argument in this paper is that, in the absence of good and empowering governance and a regulatory framework that is transparent, fair, just, empowering, pro-poor and the domestic private sector, increases in aid, FDI and remittances will not solve Ethiopia’s legendary structural poverty. Ethiopia’s priority is therefore to get its governance problem in order. The world’s obligation is not to grant more aid but unbridled commitment to human rights, the rule of law and democracy.

Introduction

With the permission of the publisher, I decided to republish this article included in a must-read book “Foreign Capital Flows and Economic Development in Africa: the impact of BRICS versus OECD,” 2017 as is with a setting added.

Today, we Ethiopians, especially those in the Diaspora are preoccupied with the tragedy inflicted on Ethiopia’s 116 million people, most of them poor. This unfolding, inexcusable and costly war triggered by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) is a huge set back in the transformation of the Ethiopian economy. It is important to imagine the untold human, financial and economic cost.

Equally important is to reflect on the lessons we must draw from this costly and inexcusable war. Ethiopian ethnic-elites cannot continue with same model of political competition and expect a transformative economy. There is no scenario I can think of under which Ethiopia can transform the structure of its agriculture-based economy without changing its governance drastically and boldly.

In this article written more than 3 years ago, I drew attention to the pitfalls of the developmental state led by the TPLF that had created favorable conditions for future ethnic conflicts. The financial, economic and resources elite capture issues embedded in the model foretold the explosive nature of conflict-prone governance in Ethiopia. Although the TPLF is on the run, the salient policy, institutional and structural hurdles that affect Ethiopia’s development remain intact.

“David Roth Kopf’s book “Superclass: The Global Power Elite and the World They Are Making” depicts the deepening gap in incomes and wealth between the few and the vast majority of the world’s poor. “The current global system seems, to many people, to be fundamentally unjust. The richest get much richer and the great majority of others struggle to remain in place,” 1/ Page 318, in Rothkopf, D. Superclass.

I subscribe to this thesis; and am weary that Africa has become a victim of globalization. I grew up in a world dominated by two superpowers: The United States and the Soviet Union. This global phenomenon changed with the collapse of the Soviet Union. For a brief period, we lived in a mono-super power world dominated by the United States. The world has changed dramatically since, with economic power shifting from West to East and South. The term BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India and China) became a vocabulary. The 21st century is increasingly governed by a multi-polar world with diverse economic and political actors. Although the evidence is not apparent yet, the so-called African Renaissance is taking place in a changing environment. This new form of globalization compels us to re-write and redefine an uncertain world in which each person is affected, with only a few controlling the levers of power; and dictating the rules of engagement. What we know is that they are not governed by democratic and inclusive governance. The Nobel Laureate Joseph Stieglitz, one of the staunchest critics of undemocratic globalization opined “Investments with high social returns were being starved” through misallocation of capital; and that the U.S. should “get out of the way and let us create an international architecture for a global economy that works for the poor.” 2/ In “America is on the wrong side of history,” paragraph 2, Joseph Stiglitz, August 7, 2015, www.ethimedia.org.

I agree with this narrative; and disagree with the Western ideology of continued hegemony that enables the rich and elites in poor countries to “get much richer; and the great majority of others remain in place. China’s efforts to establish the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank is a promising alternative in leveling the playing field. In my estimation, giving a free ride to multinational corporations, sovereign and hedge funds and state and party owned enterprises to avoid taxes on profits in African economies is a form of robbery. Stieglitz points out that “Last year, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists released information about Luxembourg’s tax rulings and exposed the scale of tax avoidance and evasion,” 3/ Paragraph 10, in “America is on the wrong side of history,” Joseph Stiglitz, August 7, 2015, www.ethimedia.org.

The poor in Ethiopia and other African countries have no say in holding their governments accountable for bribery, corruption, tax evasions and illicit outflow of capital. This suggests the need for new, democratic, and socially meaningful governance at the national and international levels. Globalization of financial capital is dictated by Western economies led by the United States; and Africa is squeezed in the process. It is not yet a full beneficiary of the evolving system. It suffered from slavery and colonialism. Africa’s 50 states are a result of the 1885 Berlin Conference designed for the benefit of colonizers; its legacy of ethnic-based economic and market fragmentation persists. In my estimation, the new system is best described as neocolonialism and Africans have minimal say.

Investments and growth are about improving peoples’ lives; and not about making the “rich and elites get richer.” Take the new country of South Sudan. It is natural resources rich; but beset by civil war. It is a prime example of the devastating effects of unfettered globalization—Bible carrying missionaries, UN Peacekeepers, American and Chinese oil, gold, uranium and farmland prospectors and investors as well as tons of NGOs and aid workers etc. South Sudan is part of the Nile Basin and its long-term importance to Egypt and North Sudan is well known. The agendas of these new “friends” do not necessarily converge with the interests of poverty-stricken black Africans. More than anything else, the poor want a better life. Ironically, immense natural resources wealth turns out to be a “curse” rather than a blessing. The poor are exploited by elites and their foreign sponsors.

Millions of African lives have been turned upside down by internal colonial bosses or warlords or rent seekers who often partner with foreign profit seekers. In many cases, local bosses are trained and or supported by foreign sponsors. South Sudan has been transformed into a country of despair, with women being raped, children malnourished and tens of thousands in refugee camps. It is this desperate situation that leads many cynics, including African intellectuals, to conclude that Africa’s new leaders are no better than their former colonizers.

At the heart of the current wave of undemocratic, cruel, and unfettered globalization is the role investment capital from which local elites benefit and the poor do not. Capitalists with surplus monies, talent and technologies leverage them to secure national resources such as farmlands, commodities such as minerals as well as markets. Money takes material shape when there are willing regimes that accommodate investments regardless of adverse social and environmental consequences. Adverse consequences are inevitable when governments are not committed to productivity, ownership of real assets such as land and are unwilling to promote justice, fair and equitable distribution of incomes and an enabling environment that sustains these.

It stuns me that decades after the end of colonialism, foreign experts have more say in African affairs than Africans. In part, this is because African governments led by rent-seeking elites trust foreigners more than their own nationals.

For example, World Bank and IMF advisors and other champions of unfettered and free market capitalism persuaded the late Prime Minister of Ethiopia, Meles Zenawi, converted Marxist, to privatize profitable and not so profitable state-owned enterprises wholesale. Hundreds of firms were privatized without clear criteria and competition. Jobs were lost. It is alleged that most of the beneficiaries are members and families of the ruling party and its endowments. Previous Ethiopian governments had adhered to the principle of private and public sector partnership in modernizing Ethiopia’s primitive economy. Meles wanted to show that he had no problem with economic liberalism if his party was the primary beneficiary. In his early days, he had admonished the East Asian Miracle stating that the working class was not the primary beneficiary and that capitalism was replete with dangers. “The Korean economic miracle was the result of a clever and pragmatic mixture of market incentives and state intervention. The Korean government did not vanquish the market as the communist states did. It did not have blind faith in the free market either. While it took markets seriously, the Korean strategy recognized that they often need to be corrected through policy intervention.” 4/ Page 15, Chang, J.H., Bad Samaritans: the myth of free trade and the secret history of capitalism.

Ethiopia’s developmental state is substantially different from Korea’s, Singapore’s, Taiwan’s, and other East Asian miracle countries in that it is party ownership that dominates the national economy. The government of Ethiopia’s does not acknowledge the enormous intellectual and policy power of global actors.

In my estimation, the power that the new form of globalization conveys is substantial. It shapes future generations. Experts estimate that the developing world accounts for half of global output. Africa’s contribution is minimal. In the coming years, this shift in economic power will be greater. We do not know whether African governments would change their governances and equip their societies in the new competitive world.

Today, China is the second largest economy in the world. Its links to Africa show that it consumes unbelievable quantities of minerals such as copper, aluminum lead, nickel, zinc accounting for 48 percent of world consumption. At the same time, Chinese investment in Africa’s infrastructure is legendary. The Third International Conference on Financing and Development in which new actors featured prominently took place in Addis Ababa welcoming the notion that Africa can absorb huge amounts of capital. Roads, bridges, ports, hydro and other electric power generation stations, rails, schools, hospitals, stadiums, villas, skyscrapers, towns, and cities are being built at a faster pace than before. Chinese investors play significant roles in this endeavor, often at the cost of socially beneficial projects. Some say that there is nothing wrong with the emphasis on infrastructure; while others contend that sustainable and equitable growth must be people-centered and anchored. The key variable in this debate is good governance on which China is deficient; and the West is timid in promoting it.

I subscribe to the fundamental principle that only accountable governments are more productive and caring than dictatorships. Growth in GDP alone will not generate productivity or increase employment.

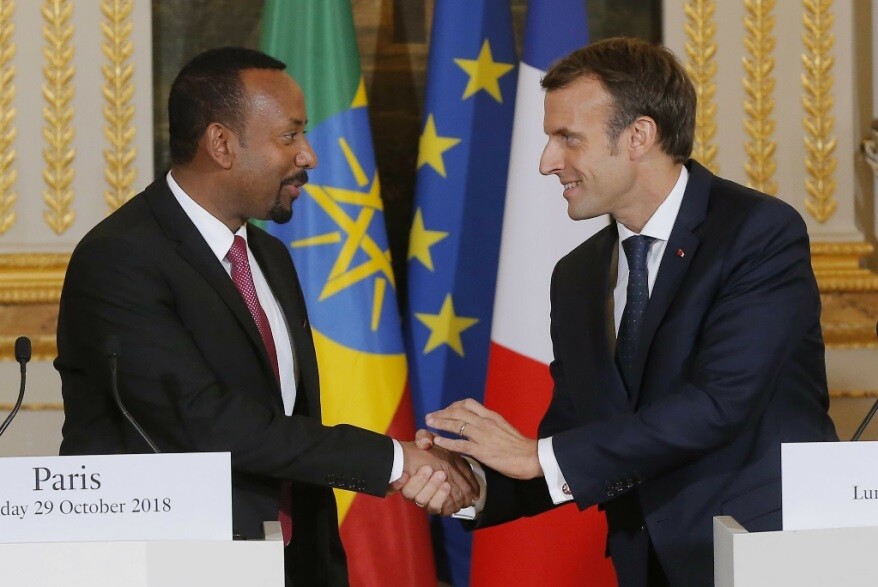

President Obama hammered the vital role of good governance during his visit to Kenya and Ethiopia. What he did not say is equally important. Africa is increasingly squeezed by investors and trade regimes led by the United States from the Western hemisphere and China.

My hypothesis for this article is this. The intense rivalry between the two is taking place, in large part, without Africans having a major say on matters that affect their lives and destinies. African government leaders meet and talk while leaving the core issue of good governance to others as if they are still colonies. Concerns about the President’s visit are therefore more than about human rights and other forms of governance. Human rights are always vital. An African who has nothing to eat or does not have a job or safe drinking water or proper shelter or sanitation etc. does not really care whether the President of the United States talks about democracy or about dictatorship. Africans know that there are good and bad dictators. I often ask myself this question. “What is in it for those who are marginalized or are being harmed by an unjust global system? What difference does it make for the tens of thousands who flee their homes in search of jobs in Western Europe and the Middle East and die on their way or are degraded when they arrive if their country receives billions in aid or FDI?”

The relevant debate in most parts of Africa today is about being independent from foreign food and other aid. It is about ownership of assets. It is about benefiting from Africa’s immense resources. It is about shaping the future for Africans by Africans.

I was struck at a meeting of Black African and Arab scholars in Doha sponsored by Al-Jazeera in November 2013 how blacks are perceived by Arabs and Westerners alike. Despite Africa’s immense intellectual capital, we Africans are not at the table in forums that affect our lives and those of our countries. This is because our countries are poor, backward, and dependent. With a few exceptions—Botswana, Mauritius, Cape Verde, South Africa, Namibia–Africa is dominated by more authoritarian governments than any other continent.

Retarding governance has barely improved after colonialism and the Cold War. The African Union is more of a club of like-minded authoritarian and corrupt leaders than a forum for good governance. We ought to acknowledge that colonial repression has been replaced by new elites and new external actors and allies who have captured political, financial, and economic institutions as well as natural resources. They have opened Africa’s womb for a new form of undemocratic globalization. This collusion of mutual interests is a threat. It is an African problem that should be solved by Africans. Whether it is the Chinese, former colonizers, the Saudis or the Americans, engagement is centered on self or national interest and not on Africa’s poor. The global architecture reinforces this phenomenon.

I subscribe to the notion that Africans can gain from fair and democratic globalization, especially in knowledge transfer. Ethiopia’s relations to the global community cannot be unconditional. It must be based on national interest and the aspirations of the Ethiopian people. “The more recent economic success stories of China, and increasingly India, are also examples that show the importance of strategic, rather than unconditional integration with the global economy based on a nationalistic vision.” 5/ Page 29, Chang, J.H., Bad Samaritans

The imperative of an Ethiopian national agenda

African countries such as Ethiopia differ from East and South Asia in numerous ways. Among these are the vagaries of ethnicity and ethnic elite political and economic capture. In other words, Ethiopia does not follow a “nationalistic vision,” the same way China or Vietnam does. I find no evidence whatsoever that the Ethiopian government is committed to a strong national private sector. It refuses to apply high tariffs to protect nascent industries. It leases large tracts of land to foreign investors. Ethiopia today is not in the hands of Ethiopians but a narrow band of ethnic elites and their global champions.

Africans forget, ignore or neglect Obama’s speech in Ghana. “We must start from the simple premise that Africa’s future is up to Africans. We may share mutual interests, but we also live in an extremely competitive world. It isn’t a zero-sum game, but the choices they make will not necessarily be to our advantage, and vice versa.”

I indicated in my book, Waves that the principle of legitimacy has been wrongly applied in colonizing and still dominating African countries. In graduate school one of my professors argued that “Portuguese colonialism of Angola, Guinea Bissau, Mozambique, and Principe/Sao Tome was legitimate,” because these Europeans were advancing modernization. I contested this hypothesis. Exploiting African resources and suppressing the population is not consistent with modernization.

The Professor’s argument that Portugal had a legitimate right under “international law” is not in synch with Western values and changing times. By his definition, “America would have remained a British colony had the settlers not revolted.” In fact, colonization creates “gross inequality” and is conflict prone. 6/ Page 61, Birara, A. Waves: Endemic Poverty that Globalization Cannot Tackle but Ethiopians Can, 2010.

Is Black Africa free?

The remnants of colonialism linger in many parts of Africa. As was the case in colonial times, gross inequality is inevitable if state and non-state actors preserve and retain financial and economic interests for a narrow band of folks in concert with global actors. The argument that global actors, especially paid experts mean no harm is a fallacy. Hundreds of thousands of foreign experts manning African institutions are paid salaries and subsidies that no African expert can ever aspire in his or her own homeland and in his or her lifetime.

Sadly, each African country has ample trained but not retained human capital. Ethiopia graduates thousands of medical doctors each year. I estimate that 2/3rd of this human capital leaves the country each year. The Ethiopian poor are subsidizing other countries. Yet, I have seen no evidence from global experts, donors and governments who admonish this bleeding. Global actors impose bad policies but do not encourage nationalist Africans to counter their views. “The Bad Samaritans have imposed macroeconomic policies on developing countries that seriously hamper their ability to invest, grow and create jobs in the long run.” 7/ Page 159, Chang, H.J., Bad Samaritans

The centrality of human capital

Trained human capital is the single most important variable in advancing African economies. If you lose your lead human capital, you lose the capacity to negotiate. African governments have thus far failed to nurture and retain this critical asset. As I travel around the world, I am struck by the number of successful Africans. For example, Ethiopians save and invest in Ethiopian restaurants anywhere in the world and make them profitable. My conclusion from this observation is that Ethiopia’s middle and upper middle class resides abroad, not in Ethiopia.

We Africans are ignoring the new actors of globalization at enormous risks for succeeding generations. Enormous profits are being made in Africa while power elites tolerate human trafficking of African youth, destitution and repression of Africans from Burkina Faso, Mali, Nigeria and Eritrea, Ethiopia, and environmental degradation everywhere. This is happening while elites live in luxuries that are beyond belief. Although not reported in official statistics, some Ethiopian officials own 100 million Birr ($20 million) palatial homes. Those who are being asked to help drought famine victims in Ethiopia find luxury during misery intolerable.

In its 2016 report of the status of African economies, the Economist reported that the number of middle-income Africans, defined as those with per capita income of $10-20 per day does not exceed 15 million people and “none is in Ethiopia,” 8/ The Economist, the World in 2016: A Revolution from Below and Continental Drift).

I chose the title “Your next “landlord” will not be Ethiopian: how globalization undermines the poor” for a sound reason. Ethiopia has ample irrigable and other farmlands. Yet, it is food aid dependent. It is one of the centers of land grab. It is the largest aid recipient in Sub-Saharan Africa and one of the largest in the world. Yet, its economic and social structures are Biblical. Its growth favors ethnic elites at the top. More than 75 percent of its population consists of youth. Yet, it floods the global market, especially the West and South Africa, with an exodus of immigrants. It is unable to create jobs, in part because the private sector is squeezed by party and endowment monopolies. It draws FDI but does not have a regulatory framework of partnership that favors the domestic private sector.

Sadly, the global community does not find anything wrong with the current system. For reasons that escape me, Ethiopia’s benefactors—donors, and friendly governments, seem to prefer stability at the cost of freedom, human rights, the rule of law and democracy. It is certainly true that in a region of failed states and terrorism, Ethiopia has not suffered the traumas of savage and senseless attacks by terrorist groups such as Al-Shabab. But for how long? Most Ethiopian intellectuals and opposition groups contend that the Ethiopian state is “terrorizing” the population. This may be debatable depending on the motive behind the characterization.

What I know is this. Ethiopia is one of the worst jailers of journalists in the world. It is one the major sources of human exodus in Africa. It suffers from one of the worst cases of nepotism, corruption, and illicit outflow. It is among the top centers for land grab and dispossession of indigenous people. It is home to the largest brothels in Africa. Girls as young as ten are traded for sex in Addis Ababa, home of the African Union.

The tragedy of Ethiopia’s young girls and land grab in Africa in general and Ethiopia illustrate the pitfalls of globalization combined with poor governance. The motives are self-serving. I remind the reader that investors are driven by three motives:

First is “the need to establish beachheads and secure reliable and reasonably priced food supplies for their clients.” This is understandable given diminished arable lands across the globe. The concern is the transfer of ownership from indigenous people to foreign and elite domestic investors.

Second is “to secure reliable and reasonably priced sources of biofuels.” Ethiopia’s top priority should be to be food self-sufficient; and therefore, to boost smallholder food productivity.

Third is to respond to “hedge funds and other investors that wish to capitalize on the commodity boom and to make money.” The Ethiopian government’s argument that the country should lease its lands, gain foreign exchange, and purchase food supplies in the open market is short-sighted. Among other things, the policy “undermines domestic capabilities and perpetuates food dependency,” 9/ Pages 218-220, Birara, A. Ethiopia: The Great Land Giveaway, 2011.

In my estimation, globalization in the form of foreign direct investment, trade, migration, remittances, the fight against terrorism does not have to be a zero-sum game. The single most important message I took from President Obama’s speech in Africa is this. If Africans, including Ethiopians, wish to transform their societies on a sustainable and transformative manner, they must do it themselves, for themselves (ourselves). No one else will do it for us.

Africans rejected colonialism and other isms; and then lost decades of growth because of dictatorships. Sadly, these other isms have been replaced by elitism, cronyism, tribalism, nepotism and political and economic captures by elites. Except for democratic Botswana, Burkina Faso, Mauritius, Cape Verde, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania, Morocco, Tunisia, Senegal and Ghana, most of Africa is still shackled by new forms of repression, exploitation and collusion. www.Legatumprosperityranking/2015).

The consequences of poor and repressive governance are staggering. For example, if we take the ten fastest growing economies in Africa, the socioeconomic situation for most Africans is either the same or worse. The difference in GDP per capita per year between Botswana at $16,000 and Ethiopia $470 to $490 is day and night. It can’t be explained by any other variable but lack of good and empowering governance. Social rates of return in Botswana are about four times higher than Ethiopia. The private sector in Botswana is more robust. Corruption in Botswana is almost zero. It is institutionalized in Ethiopia.

It is arguable that FDI, aid and trade can improve lives in a sustainable manner without accountability in governance. For example, how come Ethiopia has not achieved food self-sufficiency after $40 billion in Western development assistance?

What is development anyway?

Today, ordinary Ethiopians joke about growth in their country. In other words, their government has degraded the concept. It has made a mockery of growth by defining growth and development as top down like command economies. For me, it is freedom and empowerment. As such, it is about people. It is ownership of assets. If you wish to build a better home; you work hard, save, and invest. You cannot save if you do not have a job or are not allowed to establish a firm; or if someone comes to your home or goes to the bank and steals your savings. What is true at the individual and family level is also true at a national level. Africans are unable to keep what is theirs. There is a plethora of evidence that shows that over the past 39 years, Africa lost $1.8 trillion. This sum is staggering and debilitating. This problem is compounded by other factors and interventions.

African countries suffered immensely from structural adjustments that curtailed public spending in education, health and other social sectors. In the early 1990s, Ethiopia was compelled to privatize successful state-owned enterprises (SOEs), including those that were profitable. To this day, the government has not explained to the public to which groups and or individuals the privatized firms were transferred and what social and economic benefits Ethiopians gained. As far as I know, there was no transparency in the transactions and there was no open competition. The process was opaque. Equally worrisome is the fact that Ethiopia’s land leases and FDI are shrouded in mystery.

The volume of FDI and trade to “the new frontier,” especially to the ten fastest economies, has increased dramatically over the past decade, with FDI of $32 billion in 2013 and $29 billion in 2014. In 2013, a quarter of the inflow of $10.3 billion was invested in Nigeria and South Africa. Nigeria has the largest middle class in Africa. This is in part because of the growth role of the domestic private sector and FDI. In 2012, Mozambique attracted $7.1 billion, dedicated mostly to natural resources extraction. Other beneficiaries of FDI include Ghana, Uganda and Zambia.

One encouraging trend is diversification of the investment portfolio into media and telecommunications, technology and manufacturing. Ethiopia is paying a heavy price in the media and telecommunications sector. The party and state own this sector. Its potential to contribute to increased employment and incomes will not be realized until and unless the government deregulates and privatizes the sector as other African counties have done. I reckon that the government is reluctant to grow the telecommunications sector because of its democratization feature. Imagine millions of Ethiopian youths sharing knowledge using social media. Among other things, they may demand more freedom. And freedom is dangerous in Ethiopia. It exposes poor and rent-seeking governance. The freedom deficit is among the ingredients that give globalization a bad name.

Who invests in Africa?

It is not well known that the biggest investors in the ‘new frontier’ are not the Chinese or other Asians. Europe dominates FDI while China dominates trade. With some 104 projects and $4.6 billion, the old colonial power, the United Kingdom is by far the largest investor followed by the United States. China’s investment has risen from $392 million in 2005 to $2.5 billion in 2012. Its investment portfolio is concentrated in mining and infrastructure.

A unique feature of American investment that has attracted global attention is “Power Africa” —a commitment to light 60 million homes and businesses– to which the U.S. has committed $7 billion and the U.S. private sector $12 billion. The Blackstone Group and the Carlyle Group are the most active promoters of the project. The capital requirement to achieve “Power Africa” is more than $300 billion. African countries can meet part of this requirement if they prevent capital leakage.

Ironically, Ethiopia is investing billions of dollars in hydroelectric power generation, all of it for export. Only 17 percent of Ethiopians have access to electricity. I question the wisdom of massive investment in hydroelectric power generation while most Ethiopians literally live in “the dark ages.” In the village I left decades ago, Ethiopian rural families continue to use kerosene to light their homes at night, if they can afford it.

Who dominates trade in Africa?

When I was growing up, it was Japan that dominated trade in many countries of the world, including Africa. Today, the dominant player is China; and competition for the African market is stiff. Africa is being squeezed in the competition between China on the one hand and the West on the other. In 2011 U.S. trade with Africa amounted to $125 billion; and China’s $166 billion. Although the U.S. had initiated the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), there is little indication that access for African goods to the U.S. market has been made easier. Two-way trades have not expanded. In 2013, U.S. trade declined to $85 billion while Chinese trade rose to $213 billion. The government of China aims to increase this to $400 billion by 2020. This favors China more than Africa. Ethiopians are resentful of the Chinese because of their pervasive presence. They do not understand that China is there at the invitation of the Ethiopian government.

Make African development youth-centered

Whether FDI or trade, the central question in my mind is the extent to which Africans, especially the poor and youth, would gain. More research should be done on the role of the new form of globalization in accelerating sustainable and equitable development for Africans or doing the opposite. At minimum, there must be African governments that are dedicated to the defense and services of their own national interests and societies in the same way as developmental states in East Asia and the Pacific region. As President Obama said in Ghana, this is a highly “competitive” world in which weaker and least developed countries are at the mercy of domestic elites and global actors that often work in tandem.

Singular concentration in fighting terrorism while leaving intractable socioeconomic and political problems that breed terrorism, civil conflict, balkanization, capital flight untouched and un-discussed is not a winning strategy. And the West is partly to blame for not addressing this phenomenon.

Farmlands and water grabbing in the new frontier

A prime example of greed during poverty is land grab by foreign investors and domestic elites. FDI in farmlands in Africa is a new form of “colonialism.” In all cases, investments disadvantage poorly governed countries such as Ethiopia. There are no rules, regulations, and protocols to protect the poor; and Ethiopia’s national interests and sovereignty are compromised. Countries dominated by repressive regimes are always characterized by weak institutions. There is no community or civic voice or independent media to mitigate risks.

My argument is that benefits depend on the existence of nationally oriented, competent, and highly dedicated government leaders and institutions that negotiate, defend, and protect the indigenous population. FDI does not advance public welfare unless authorities defend the interests of their societies. The fact that economic power shifts from West to East does not mean that poor countries can do better. There are no transparent and shared rules and arrangements that govern investments. The poor and domestic investors are left on their own.

Land grab is an excellent example of poor and repressive elite governance in Ethiopia. Land grab means expropriation. The regime expropriates and gives farmlands away to the highest bidder without any open competition or compensation. The reason is simple. It is to ensure single party dominance over the national economy. When I contrast unbridled FDI in commercial agriculture in Ethiopia with countries that negotiate the best deals for their societies, I discover that Ethiopia sold or leased its farmlands and water basins for nothing. In the process, the government dispossessed millions in the process.

Despite lack of a new global inclusive and just architecture in conducting business, there is no evidence that supports that nationally oriented and committed governments give away the most critical source of current and future comparative advantage to investors for free. They ensure that their populations are given priority over foreign investors. Repressive and corrupt regimes give away natural resources including fertile farmlands for short-term gains such as foreign exchange. When this occurs, the social, economic, and environmental effects are huge. Families, communities, and the entire society lose control of a key natural resource that defines their culture, identity, potential source of prosperity and security.

What drives this new phenomenon? At the start of 2011, the Ethiopian government had leased or sold 3 million hectares of farmlands to foreign investors, an amount that is almost 30,000 square kilometers. “In mid-April 2011, a pro-government newspaper, the Reporter, confirmed that regional states had voluntarily transferred to the Federal Government of Ethiopia 3, 638, 415 million hectares” for the purpose of leasing them to foreign and selected domestic investors…..We know that 900 permits and licenses were granted.” 10/ Page 218, Birara, A., Ethiopia: the Great Land Giveaway.

Regional governments are run by ethnic elites. They benefit from land transfers. Land is the primary source of nepotism, bribery and corruption in Ethiopia. Ethiopia’s land giveaway did not generate outcry among elites or the opposition because of self-interest and fear. Further, Ethiopians are ill informed and confused about the meaning of development and the role of land grab in achieving growth goals. Ever since I remember, two extreme classes have characterized Ethiopia: the rich and super rich at the top and the poorest of the poor at the bottom.

For the past half-century, the country provided ground to the poverty alleviation business. Aid is received on behalf of the poor; but enriches the few. This is where I would center the growth and development debate. It must be people-centered and not ethnic-elite centered. Without it, one cannot understand the political economy of poor governance and transfer of natural resources to investors. Without it, we cannot understand why there is widespread conflict among ethnic elites for control of natural resources. The distinction I made between Botswana and Ethiopia refers to the two extremes. Ethiopia does not have a middle class. It has a few millionaires. Botswana has a growing middle class. Millions of Ethiopians starve; there is no starvation in Botswana. The difference is accountable and democratic governance in Botswana and dictatorial governance in Ethiopia.

Foreign experts and visitors travel to Ethiopia and declare that the country is hopelessly poor, while recognizing physical change. Physical infrastructure has had a glitz effect masking deep policy and structural hurdles that Ethiopia faces. The hopelessness arises from abject poverty that they see everywhere. The World Bank defines the middle class as those who earn $10 per day (Brazil) and $20 per day (Italy). In Ethiopia 90 percent of the population is multidimensionality poor. In 2000, 430 million people belonged to the middle class. The projection by different institutions including McKinsey and Company is that this number will rise to 1.15 billion by 2030.

By 2000, China grew its middle class to 100 million people. McKinsey projects that this number will grow to 140 million by 2015. Therefore, I argue that poverty reduction in Ethiopia must be measured by the rise of the middle class. It is when the poor eat three meals a day, send their children to school and have accesses to economic opportunities that substantial rise in the middle class will occur. The current system grows incomes and assets for the rich and super rich but does not enhance opportunities for the poor.

Land is among the most important variables in the equation. How it is allocated, developed, and used determines the extent to which those at the bottom would rise to the middle. This class will produce and consume large quantities of domestically manufactured goods, foods, and services. It will enlarge the government’s tax revenue base. It will demand accountability from its government. Now the two extremes are stuck. The poor do not have the time or freedom or resources to demand accountability as much as the middle class. For the regime in power, it pays to keep the poor where they are.

The second organizing principle is that the Ethiopian regime seems to market the notion that a large chunk of fertile farmlands and waters in Gambella can be transferred to foreign ownership to grow and develop the region. Millions of hectares of farmlands have been or will soon be transferred to investors. The developmental argument of forcibly removing inhabitants to lift them out of destitution is absurd and immoral. How many ordinary people in Gambella would enter the middle class if they are marginalized? What would be their social rates of return? Would reliance on commodity exports owned by foreigners and for foreigners induce a middle class and pave the way for sustainable and equitable development? Gambella illustrates this is not the case.

Most of the population falls into the lowest level of income and material poverty. Therefore, I gave this article the title “Your next ‘landlord’ will not be Ethiopian.” An Indian commercial farm manager in Gambella said it best. “They gave it to us, and we took it. We did not even see the place.” Karuturi is one of 896 foreign investors that scramble for a piece of the action in Gambella and other locations. At the height of “farmland colonization by invitation,” at least 36 governments were involved. On March 21, 2011, John Vidal of the Guardian Co., UK newspaper chain presented a heart-wrenching documentary on the social, economic and environmental implications of disenfranchisement that comes from transfers of ownership from Ethiopians to foreign investors. One commercial farm of 100,000 hectares of emerald green land is as “big as Wales” in the United Kingdom. The 300,000 hectares plus land offered to Karuturi, one of the largest “landlords” in Ethiopia stretches 1,000 square miles and displaces entire villages. Vidal offers a vivid picture of 250 people left stranded for “8 months.” 11/ Page 152, Birara, A., Ethiopia: The Great Land Giveaway.

Land as big as “Wales and Luxembourg” represents more than geography. It represents people and their futures. The heart-wrenching story I suggest comes from people who are uprooted and full of fear. Vidal quotes people under conditions of anonymity. We “are scared to talk. Who cares about us; they will jail me.” Utterances such as these do not indicate consent, but coercion. “They gave it to us, and we took it.” What this says to me is “Do not blame us; ask the Ethiopian government that granted us these lands.”

Accountability for social, economic, and environmental outcomes resides with the regime. “Who cares about us” is a story about the poor, and the callousness of their government. At the peak of land transfers to 896 licensees in 2007 when the regime earned more than $3.00 billion, thousands of inhabitants in Beni-Shangul and Gambella were forced to move. Officials told Vidal that resettlement was voluntary and developmental. Villages razed to the ground, the poor had extraordinarily little choice but to move. Officials argue that the primary reason for resettlement is the need to accelerate social and infrastructural development; and that it is virtually impossible and uneconomical to provide social services to scattered villages. This is true; and has been for the past 25 years under the watch of the current regime.

Is it coincidental that resettlements are speeded up to meet a development gap? It does not seem to be that way. Relocation is planned and deliberated as part of the transfers. On November 29, 2010, William Davison of Bloomberg news reported that 150,000 households or 750,000 people from the Afar, Beni-Shangul Gumuz, Gambella and Ogaden regions would be resettled. What is heart wrenching is the reaction of indigenous people, victims of land grab in the name of development. “We are deceived by our government.” 12/ Page 257, Birara, A., Ethiopia: the Great Land Giveaway.

In “Public Backlash against Forced Evictions from Land a Certainty,” posted by the Solidarity Movement for a New Ethiopia, one learns the magnitude and growing resentments that John Vidal underscored in his documentary. Solidarity says, ¾ of the population of Gambella is slated to move. Assuming a population of 225,000, it means close to 170,000 people would need to move. This amounts to effective evacuation of the majority to make room for large-scale commercial farms. “Villagization” is a deliberate program of the government and is a result of land grab. In the initial phase, officials promised 3 to 4 hectares of farmlands for each household; but only 60, 000 hectares are set aside. It is equivalent to 1.3 hectares per household in a region that is giving up 1.8 million hectares to investors. As enticements, inhabitants are promised schools, health facilities, market sites, roads and the like. No high school or higher education is planned by either the government or investors. Inhabitants complain that the minimal promises from the government that earns billions of dollars from land sales and leases are not often kept. Without quality education and accesses to new economic opportunities, it is unlikely that the people of Afar, Beni-Shangul Gumuz, Gambella or Ogaden would see increases in incomes. What is predictable is continued poverty, inequality, and instability.

Karuturi’s holding of 300,000 hectares is accompanied by Saudi Star that owns between 300, 000 and 500,000 hectares in Gambella. It has similar projects in Beni-Shangul Gumuz. The “new landlords” are diverse for strategic reasons, I believe 36 countries and 896 separate licenses are diverse. These investments cannot possibly take place without adverse effects on inhabitants and the environment. The government is silly in not acknowledging that land transfers to investors entail huge costs. In the words of an Anuak cited earlier “If these people think they will come here, remove us by force from our ancestral land for mega-farms and think they will succeed in harvesting their crops without any resistance, they are wrong. The only way they will be right in thinking this is if their crops remain green; and ready to harvest forever.”

I fully understand the agony of this Ethiopian. The Indian representative says the Ethiopian government “Gave it to us, and we took it. Seriously, we did not even see the land. They offered it. That is all.” This is the reason for my thesis that farmland and water basin transfers or giveaways to foreign investors are effectively “farmland colonization by invitation.” People are simply “scared to talk.” The developmental economics point of the regime fits the definition of “survival of the fittest” model of thinking. It is only those with political influence and their allies who could not only survive but thrive. Under this inequitable model the world seems to condone, one would have to wonder for how long people would live with the model itself.

My sense is that it will perpetuate the extremes of elites and the poor and ignite civil conflict. Public backlash is inevitable. The totality of potential adverse effects leads Vidal to call the transfers the “deal of the century.” After visiting with government officials at all levels and learning the party line, he asks the penultimate question, “Is it in the people’s best interest” that the regime gave away their sources of current and future comparative advantage and prosperity. My conclusion is none. This is the reason why the 21st century version of globalization is perceived as unjust. The uprising in Oromia in early 2016 reveals the dilemma of political and economic capture, especially lands, by a minority ethnic group and the marginalization of millions.

Is there a way out?

I believe there is. It requires political will. In summary, I come up with the following conclusions.

First and foremost, Africans must straighten out their own governments. They must believe in themselves and hold their governments accountable for outcomes. This occurs when good governance is institutionalized.

Equally, the global community, especially FDI must be governed by new, inclusive, democratic, and accountable governance architecture. I suggest we use parameters against which both can be assessed. The most important parameter is the wellbeing of most of the poor.

In this regard, economic and social rates of return from investments in natural resource must be equally beneficial to Ethiopian society. They must improve the value-chain by enabling Ethiopians to be producers, income earners, food processors, manufactures, exporters, consumers and so on. As designed, the value-added of foreign owned large-scale commercial farms accrues to investors. Ethiopians are not only disenfranchised from transfers of an estimated 30,000 square kilometers of their most fertile farmlands and water basins; they do not play roles in the development process. There are no food processing plants. There are no Agric-based manufacturing economic activities adjacent to the farms. There are no meaningful additional physical or social infrastructure projects that connect various sectors. These investments do not grow the national economy in ways that will make it self-reliant and independent. Millions of Ethiopians live in extreme poverty earning less than $1.25 a day. Escalating food prices diminish this meager earning further.

At the annual spring meetings of the IMF and the World Bank in April 2011, the President of the World Bank had warned “on the threat of social unrest” driven by escalating food prices and unemployment. When food prices persist upwards, it is the poorest of the poor who suffer most.

The jigsaw puzzle of development policy of the Ethiopian ruling party in giving away farmlands to foreign investors while importing food will, inevitably lead to the tensions the World Bank and others have in mind. These transfers deny Ethiopians the benefits that arise from ownership and control. The value-added from “processing, marketing and distributing” of produces in their own homeland go to investors. Accordingly, the “deal of the century” enriches investors while deepening Ethiopia’s poverty. This unbelievable deal is not governed by any code of business conduct to mitigate risks for Ethiopian households, communities, and society.

The deals do not induce food self-sufficiency. The regime neglects key lessons from the North

African and Middle East uprisings. According to a statement from Robert Zoellick, President of the World Bank, “We should remember that the revolution in Tunisia started with the self-immolation of a fruit seller who was harassed by authorities.” Farmland giveaways to foreign and a selected few domestic are imposed by Ethiopian authorities without clear and predictable benefits to the Ethiopian people. They dispossess inhabitants. When a government dispossesses its own citizens, it invites civil conflict. Widespread civil conflict spares no one, including the physical properties of foreign and domestic investors.

Second, these farmlands are sources of comparative advantage for Ethiopia and could be transformed into granaries for exports and domestic consumption. Building national institutions and strengthening domestic capabilities will generate private sector enterprises and employment, boost agricultural productivity and make the country more competitive. Given favorable conditions-instead of foreign investors–it will be Ethiopians who will be able to export agricultural produce to Chinese, Egyptian, Saudi and Indian markets. Empowering foreign “landlords” is the opposite policy.

Third, terms and conditions do not state clearly and openly that these large-scale commercial farms will generate permanent employment and that wages and benefits will lift employees from poverty. On the contrary, low wages will keep Ethiopian workers poor. This is no way to achieve middle income status. These Ethiopians will be condemned to endure the indignity of working for “new landlords” who happen to be non-Ethiopian in a sector where the country has a solid history and potential for a smallholder “green revolution.”

Fourth, Ethiopia has a track record that governs FDI. This comes in the form of 51 percent domestic ownership and 49 percent foreign ownership, standardized under the Imperial regime. The regime was ahead because it was nationalistic and wanted to protect the country’s interests. Land deals under the current government do not manifest this best practice in natural resource management.

Fifth, whether unoccupied or occupied, fertile farmlands belong to specific groups. Their involvement and participation in decision-making is vital. The governing party has not shown any inclination to engage them. Decisions create unnecessary tensions and conflicts that could have been avoided. This is the social missing link. The fact that lands are not occupied is irrelevant. Unoccupied lands can be leased in a responsible manner, with the Ethiopian people in control of their natural resources for their benefits. Ethiopian communities are stakeholders and deserve to be heard. Those hired must feel that their government stands on their side.

There must be linkage to other sectors of the economy. Workers should not be expected to live with ‘slavery wage rates’ working on farmlands in their own home country. Ethiopians are forced to work for “foreign bosses” in a sector about which they know something. There are numerous Ethiopians with technical and managerial talent to manage large-scale commercial farms. Farming is a national tradition that goes back thousands of years. The role of government is to equip smallholders and others with the tools they need to increase productivity and employment. It is not to make tenants and “strangers” in their own lands.

Sixth, when a regime gives away farmlands or other natural resources without engaging foreign corporations to agree to terms and conditions that will advance the interests of households, communities, and the entire society, it is legitimate to question the ultimate objective of the deals.

Beneficial FDI is always based on shared benefit and is publicized to educate the public. Nationalistic governments ensure that there is no environmental destruction. Ethiopia has a history of environmental degradation. The landmass that is forested and needs custodianship is much smaller than it used to be. There is ample evidence in Gambella and other localities that shows catastrophic levels of clearing of virgin and irreplaceable forests as well as streams. The flora and fauna as well as the natural resources used by households and communities to earn a living are being destroyed.

For example, households harvest honey to earn incomes and to sustain livelihoods. This will not occur when the forest is cleared. Inhabitants use streams and rivers to fish, earn incomes and sustain lives. This disappears when foreign corporations dam and divert rivers to support their large commercial farms. Eliminating livelihood to make way for FDI without offering meaningful alternatives is irreprehensible in a country that “begs” for food. The social and environmental impacts of these unregulated clearings by investors are catastrophic and irreversible. Future generations of Ethiopians will suffer from these destructions. These are among the reasons why I question the deals.

Equally, natural resources capture of lands and water resources in Ethiopia reflects political capture by elites who find nothing wrong with FDI. Elites are the lead beneficiaries of this phenomenon. The problem is this. Concentration of incomes and wealth is hugely risky for Ethiopia. It creates inequality and poverty and leads to social and political instability and terrorism. Eventually, people revolt because economic and social opportunities are closed. Those who are rich do not feel safe and flee with their capital. Their homes and enterprises become easy targets for the outraged. This actually happened recently when Oromo youth targeted and burned investments properties because they were outraged by government brutality.

It narrows the domestic savings and consumer base and reduces productivity, consumption and competition. Poor people cannot buy, and rich enterprises cannot expand markets. Inequality and unfair practices force domestic investors to leave with their capital. This is the reason for massive illicit outflow of capital.

When talent leaves the country in droves it reduces social capital. Ethiopia suffers from the worst human exodus in its long history. Ethiopia will not have social and financial capital, technology or managerial talent to manage and use its natural resource effectively. This forces it to invite foreign investors to do as they wish. Ethiopians lose control of their destinies and Ethiopia losses its sovereignty.

Sadly, the regime allows natural resource exploitation because it gains from collusion with FDI.

Ethiopia cannot afford to emulate income and wealth inequality as a sustainable development model. Control of the commanding heights of the economy by a single party proves to be a sure way of aggravating income inequality, future social fissures and dependency on foreigners. Showing a few success stories here and there–such as cut flower exports without diversification and expansion of economic opportunities for large numbers of people–does not suggest that the lives of ordinary Ethiopians are improving, and that Ethiopia’s middle class is exploding. More critical, this model does not illustrate that Ethiopians are in control of their future. Millions of people find it difficult to eat two meals a day in a country that is giving away its fertile farmlands to foreign investors.

This leads me to critique the “win-win” proposition advanced by such entities as IFC and private sector multinationals, hedge funds and rich individuals that lack intellectual honesty. They suggest that FDI in commercial farming is critical for Africa. FDI in commercial farms is not altruistic. The primary motive is to make profits, secure food sources and alternatives to fossil fuel. Investors are helped by the convergence of domestic economic, financial and political and class interests.

Just imagine how the poor can survive this well financed assault on their social, economic and cultural rights. In one form or another the principle applied is availability of untapped farmlands, markets and rural poverty. Consequences on communities and the environment are immaterial. In a capital and technology poor country such as Ethiopia, there is nothing wrong in investing in fertile farmlands that would alleviate world demand for foods and biofuels while contributing to the development process. The question is “For whom and how?” Sustainability and equity are vital in development. Without both, growth is meaningless, and chaos is inevitable.

I find it find ironic that the World Bank, IFPRI and others agree on a set of principles that should govern investments in farmlands. In Africa, principles dictated by “Good Samaritans” are a dime a dozen. They dictate them but do nothing to push these principles on the Ethiopian government and on investors. Instead, they have watched the regime push and impose on the poor and defenseless a laissez-faire development model that many nationalist governments would find repulsive.

As far as I know no one is held accountable for failures for social and environmental degradation in Africa. And Ethiopia is the worst example of this. Because fundamental principles are not enforced, interethnic conflict and terrorism will flourish.

The global community must acknowledge the enormous gap between intentions and deeds on the ground that makes the global system un-trustworthy and unreliable for the poor. Most Africans disenchanted with this unjust system ask the pertinent question “Where is the moral obligation to make repressive governments and FDI accountable to communities, the society and future generations?” If there is one notion that has given unregulated capitalism a bad name, it is corruption and greed. Un-regulated FDI is full of greed. In Ethiopia, greed among official and nonofficial loyal to the governing party is legendary. Ethiopia continues to lose billions in illicit outflow of capital each year.

Greed put the world capitalist system on the brink of collapse in 2008/2009 and threatens its very existence today. FDI in farmlands is full of greed. Firms such as Saudi Star and Karuturi and numerous hedge funds and individual investors are not in Ethiopia to alleviate poverty, feed the hungry and end dependency. They are not the “Mother Teresa” of the Ethiopian poor and never will be. No one blames them for exploiting the country’s natural resources and human capital. They are there at the invitation of the Ethiopian government. The transnational corporations that command billions of dollars in investment assets found a willing and inviting partner at the top of the decision-making pyramid and are making full use of it.

Investors do not feel obligated to apply any fair and just principle. Firms operate with political and social classes within the country and feel immune from public scrutiny. Although I have focused on Ethiopia, with a few exceptions, the entire Africa illustrates a recurring dilemma.

Natural resource endowments have become a curse. This is the reason why, each year, hundreds of thousands of African youths leave their homes and families in search of opportunities in Europe and elsewhere. Ethiopia is among the top contributors to this exodus. Building physical infrastructure such as roads, rails, dams, lavish villas and skyscrapers is fairly easy if you receive billions in aid monies.

The acid test of credible growth in Ethiopia is the extent to which most citizens eat three meals a day, enjoy freedom, better health, safe drinking water and better sanitation; and youth look forward to employment opportunities after they complete their education. As an Ethiopian friend confided, “You cannot eat the Renaissance Dam. Can you.”

Sadly, I conclude with my repeated claim of collusion between global capital and domestic elites at enormous costs for households, communities, and the entire Ethiopian society. This is not a “win -win” proposition. Instead, it should be labeled “Welcome to your ‘new landlord’ who is not Ethiopian.” I am convinced that Ethiopians and other Africans can come up with better governance and regulatory alternatives if they have freedom.

Citations

1/ Rothkopf, D. Superclass: the Global Power Elite and the World They Are Making, October, 2007

2/ America is on the wrong side of history, paragraph 2, By Joseph Stiglitz August 7, 2015 WWW.Ethiomedia.org

3/ Ibid, paragraph 10

4/ Chang, H.J. Bad Samaritans: the Myth of Free Trade and the History of Capitalism, Bloomsbury Press, 2008.

5/ Ibid

6/ Birara A. Waves: Endemic Poverty that Globalization Can’t Tackle but Ethiopians Can, Signature Books, 2010

7/ Chang, H.J. Bad Samaritans: the Myth of Free Trade and the History of Capitalism, Bloomsbury Press, 2008

8/ the Economist, the World in 2016: A Revolution from Below and Continental Drift) www.economist.org

9/ Birara, A. Ethiopia: the Great Land Giveaway, Signature Books, 2011

10/ Ibid

11/ Ibid

12/ Ibid

References

Birara, A. ድርጅታዊ ምዝበራ (Organized Plunder), Maple Creek Media, 2013

Keller, K. “Technology and social change is a two-way street.” Foreshadowing the future: the impact of demography, School of Advanced International Studies. Washington, DC. 2010/11

“African Presidents and Prime Ministers: performance index for 2010-2011.” East African Journal.

January 2011

2011 Index of Economic Freedom, the Heritage Foundation and Wall Street Journal. January, 2011.

The 2010 Freedom House Political and Civil Rights Index. Freedom House. Washington, D.C. 2011.

Dulane, A. “Ethiopia: an appealing destination in Africa.” Japan Spotlight. September/October, 2010.

“Mining Fight Shows Pressure on Multinationals,” Wall Street Journal. January 27, 2011.

“A Continent of New Consumers Beckons,” Wall Street Journal. January, 2011.

Daniel, S. and Mittal, A. “Mis-investment in agriculture: the role of the International Finance Corporation in the Global Land-Grabs,” Oakland Institute. 2010.

Borras, S. and Franco, J. “From Threat to Opportunity: problems with the idea of ‘Code of Conduct” for land grabbing, Yale Human Rights and Law Journal. Vol. 13, No. 2. 2010.

Rising Global Interest in Farmlands: can it yield sustainable and equitable benefits? World Bank. September, 2010.

Pingali, P. Ending the debate over the world’s small farmers, Posted 10/13/2010.

Vidal, J. “How food and water are driving a 21st century African land grabs.” The Guardian Co., UK, March 7, 2010

Debdebo, A. “Tearing down Ethiopian society through land seizures,” Posted 11/28/2011

Ayano, F.M. Agrarian Law and Economic Development: the case of Ethiopia, Unpublished thesis. Harvard University Law School, May 2009

Keiger, D. The Curse of the Golden Egg: why are resource-rich African countries plagued by slow growth, economic disparity, corrupt and repressive governments, and civil strife? Johns Hopkins University Magazine, spring 2011.

Tamirat, I. and team. Policy and Institutional Assessment Framework: Large-scale acquisition of land rights for agricultural or natural resource use: Ethiopia, Unpublished report, World Bank. January 2010.

Deininger, K. Land Policies for Growth and Poverty Reduction, Oxford University Press and the World Bank. 2003

Government of Ethiopia, Federal Investment Bureau, Charting our Future: economic frameworks inform decision-making, Addis Ababa, 2009

Solidarity Movement for a New Ethiopia, Public backlash against forced eviction from land a certainty, January 3, 2011

Degu, L. Justifiable concerns over Ethiopia’s reckless farmland deals, posted on Ethiomedia, March, 2010.

United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Illicit Financial Flow from the Least Developed Countries: 1990-2008. New York, May, 2010.

Human Rights Watch. Development without Freedom, October 19, 2010

Wallis, J, England, A and Manson, K. Ripe, Reappraisal: Africa, the Financial Times, May 19, 2011 World Economic Forum, the Global Competitiveness Report, 2010/2011. Geneva http://Web.worldbank.org/Website/External/Countries/Africa.EXT/Ethiopia.

The Legatum Prosperity Index, 2010/2012/2015

Furtado, X and Smith, J. Ethiopia: Aid, ownership and Sovereignty. Global Governance working paper 2007/2B

Moyo, D. Dead Aid, Farrar, Strauss and Giroux. New York. 2009

Wrong, M. It is Our Time to Eat: the story of a Kenyan whistleblower. Harper/Collins, 2009 Oxford University Multidimensional Poverty Index, 2010 http://Web.UNICEF.org/Ethiopia. 2003-2008

Reich, A. Robert. After Shock: the next economy and America’s future. Alfred A. Knopf. New York. 2010.