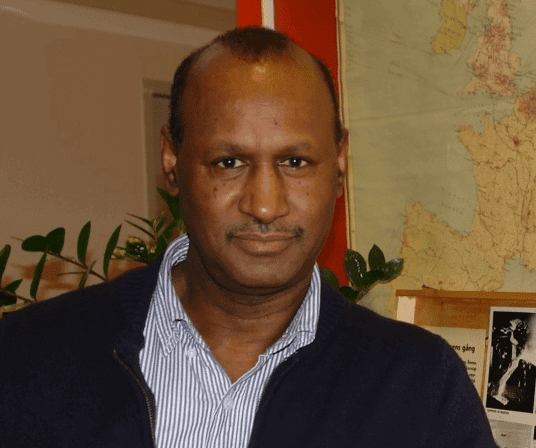

by Jawar Mohammed

The self-immolation of Ethiopian high school teacher, Yenesew Gebre, 29, signals a clear message to Ethiopian leaders and their international supporters. In Ethiopian politics, practically everything is contested, a contest that has often taken an ugly face leading to arrests, tortures and disappearances of dissidents. The growing clampdown on dissent targets leaders of opposition political parties, activists, and even bystanders with no clear association with what the government alleges to be their offense. But self-immolation in a society known for its unbreakable faith, and perseverance has shaken the social conscience of many.

However, this act of self-immolation seems to have been received with mixed feelings just like any other “garden variety” acts of opposition. On the one hand, comments on the news of Yenesew’s death across various Ethiopian websites range from “its an act of suicide, desperation, insanity”, to “its unwise, copy-paste” etc. No word from the government so far on the incident but it is hard to expect a different characterization will be forthcoming. My prediction is, the government will deny, misrepresent or simply ignore it. On the other hand, of course, the news has shaken an overwhelming majority of Ethiopians.

Yenesew, who was of Dawaro district from the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s region, holds a bachelor’s degree that normally earns an average living standard in such a community. Although he belonged to the social class that is hard hit with the current economic crisis and political repression in the country-civil servants in opposition dominated community, it is difficult to characterize his act as suicidal or politically irrelevant, or even an ordinary act of protest for economic and political injustice.

Ethiopians today face an unspeakable magnitude of economic hardship and political repression. The government’s misguided macro-economic policies and resource mismanagement has resulted in a steeply rising cost of living over the last several years. Despite the projected growth numbers thrown around, Ethiopians are living under a heavy and dehumanizing economic stress while inflation and drought-induced famine is wrecking the country. The regime’s effort to window dress the problem has utterly failed. For example, a 39% increase in salary for civil servants was drowned by 40% inflation within months. The failed imposition of a price cap on basic goods was revoked after it has done a good deal of harm and sufficiently disclosed the brute nature of the regime to do whatever it wants.

At this time, an average cost of living in urban areas is estimated to be several times a teacher’s average salary. The average salary for a civil servant is about $60/month. The spike in the cost of living has made it impossible for civil servants, who are the sole breadwinners for several dependents including their children, elders, and relatives, to fulfill their obligation. Worse, civil servants who usually are expected to take care of kins in rural areas are now becoming dependents on their family who has to support them by sending grains.

These dire economic grievances are aggravated by extreme political repression and abuse of dissent by the ruling party functionaries. Formal or informal complaints regarding the economic situation are met with distortion, which automatically places one in the opposition camp and an enemy of the state. We’ve seen rampant terrorism charges over the last few weeks.

Following the 2005 election, areas that voted for the opposition were targeted for administrative discrimination in the form of food aid, fertilizer distribution or construction of infrastructure. In the southern region, where its over 50 constituent ethnic groups were once given provincial or district level self-rule, the punishment for voting in favor of the opposition was the denial of their self-rule. Reportedly, the Dawaro community has petitioned the government to restore their right to self-rule. Instead of addressing their legitimate grievances, the regime accused civil servants and the youth for agitating the elders to petition the government, for being agents of opposition party, and threw them to jail.

Yenesaw’s self-immolation symbolizes an ultimate form of protest, a grand act of disobedience and public refusal to submit to illegitimate authority and an uncompromising rejection of a life of subordination. It signifies a kind of virtuous life one should live. He demonstrated by example that one should not live as a subordinate of another human being.

Lest we forget: His death was not about what form of political organization we should prefer, it was not about ethnic federalism or unity. It was not about local government and administration of justice. It was not about detention of a few youth even if detention was by mistake or illegal. It was not about the government’s inability to address administrative grievances. It was a decision that a life of humiliation, subordination, and betrayal is not worth living. It was a call to humanity, an appeal to the best in us, and a call to reject authoritarianism in all its forms.

—–

*Jawar Mohammed is a graduate student at Columbia University, New York. He can be reached at jawarmd@gmail.com