Laetitia Bader

Director, HRW Horn of Africa

Since armed conflict broke out in Tigray in late 2020, the European Union has said that accountability would be central to any renewed engagement with the Ethiopian government. So have its member states. During a January 2023 trip to Ethiopia, Annalena Baerbock, Germany’s foreign minister, said it was essential to address human rights violations to enable reconciliation.

When the fighting was at its peak, the EU helped push the needle on accountability. It spearheaded the establishment of the International Commission of Human Rights Experts on Ethiopia, an independent inquiry collecting and preserving evidence of international crimes for future prosecutions under the United Nations Human Rights Council.

With the commission’s renewal up for discussion at the Human Rights Council in September, the jury is still out on whether the EU and its member states will continue to support critical investigations. Or, instead, seek smoother relations with Ethiopia and accept Ethiopia’s largely window-dressing accountability measures, which are unlikely to secure victims’ access to credible justice.

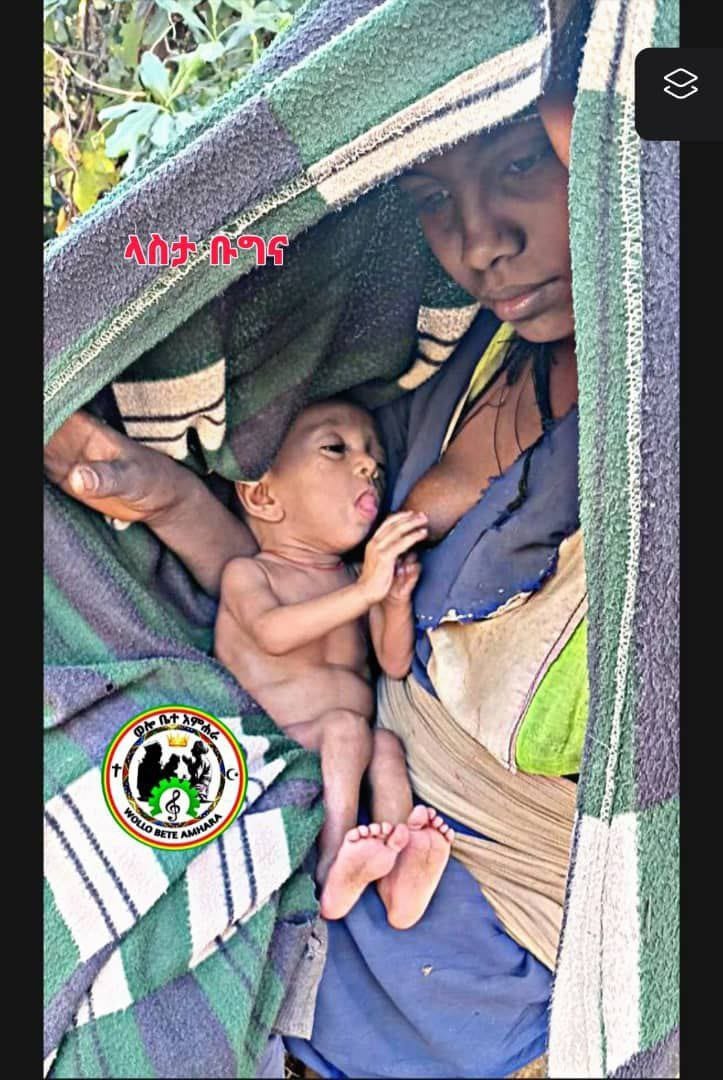

Ethiopia’s conflict has been brutal. The warring parties have broken every rule in the book, committing mass summary killings, sexual violence, and deliberately attacking healthcare facilities. The federal government and its allies have used starvation as a weapon of war in Tigray and oversaw an ethnic cleansing campaign.

Despite a ceasefire agreement in late 2022, Eritrean forces controlling parts of Tigray have obstructed humanitarian access while Amhara forces continued to commit ethnic cleansing of Tigrayans from Western Tigray Zone.

Elsewhere in Ethiopia, civilians are still bearing the brunt of hostilities. Since April, civilians in the Amhara region have been caught up in fighting between the Ethiopian military and Amhara militias; the federal government recently declared a sweeping state of emergency there. In Oromia, an abusive counterinsurgency campaign against an armed group has been underway since 2019.

The government has fiercely opposed calls for independent investigations of atrocities during the conflict in northern Ethiopia, while failing to deliver credible justice and redress. The government has repeatedly sought to shut down independent investigations, including an African Union inquiry, and has callously controlled what rights reporting has been allowed to take place, apparently to shield its forces and allies from accountability.

As reports of atrocities mounted in early 2021, the government finally agreed to an investigation on its terms. It accepted a joint investigation by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights alongside the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission. To follow up on that report, which failed to produce a full reckoning of events, the government then set up a task force to oversee redress and accountability measures. But the task force has not released its findings into events in Tigray.

Almost three years after the outbreak of conflict in northern Ethiopia, victims of some of the most serious abuses are no closer to seeing meaningful accountability. The government has repeatedly referred to a handful of prosecutions before the military courts, without any clarity about the rank of the accused, the nature of the crimes, or the outcome of those cases.

That the government has not meaningfully followed up on investigations is no surprise. Successive Ethiopian governments have never allowed for credible investigations into past or more recent serious violations, or implemented genuine measures that would ensure key elements of transitional justice.

More recently, the government has allowed the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission and the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to monitor abuses in northern Ethiopia. But monitoring cannot replace the sort of in-depth investigations and evidence preservation work that an international investigative mechanism is mandated to do.

The government of course knows the difference. It has used every tool in the box to derail international action and undermine the international commission’s work– denying investigators access to conflict-affected areas, attempting to get the commission defunded on two occasions, and lobbying to prematurely terminate its mandate.

Since early January, the government has conveniently pivoted toward a transitional justice process that emphasizes reconciliation and downplays criminal prosecutions.

Some EU and member states diplomats argue that they should give the Ethiopian government a chance to demonstrate its willingness to ensure transitional justice. But they’ve also resigned themselves to a very low bar of domestic accountability steps.

In their April 2023 conclusions on the future of EU engagement with Ethiopia, EU foreign ministers largely overlooked the lack of progress on domestic accountability and even failed to publicly call on the Ethiopian government to cooperate with the commission.

And yet, the EU knows that without building a strong foundation of evidence, there will be no meaningful justice for war crimes domestically or internationally. As abuses continue in Ethiopia, that evidence is unlikely to be collected without continued and robust independent investigations that are willing to identify responsible actors who should be held to account.

At the Human Rights Council in September, the EU needs to show leadership to rally support for meaningful accountability down the line by pushing for the renewal of the international commission. Anything less would be an abnegation of the very commitments that EU leaders at the highest levels have made and would send a clear message that victims’ calls for credible justice don’t count.