Dawit W Giorgis

December 2, 2020

- Extract from the detail research to be found in africaisss.org) by Dawit W Giorgis

Over 60% of Africa’s population is under 25 years of age. Youth poverty is higher than in any other region. It has become chronic and is rising. As young people are driven to desperation, many are resorting to crime or become involved with organized crime. It is generally believed by many close observers that Africa’s vulnerability to violent extremism is deepening. Half of the continent’s population lives below the poverty line, and many of its young people are chronically underemployed, making them vulnerable to recruitment. One attractive sector is joining extremist organizations. Members of violent extremist groups are disproportionally young men and they are geographically dispersed.

Recruitment efforts by extremist groups are focused mainly on youth. They make it easy to join: one does not have to belong to a particular country or ethnic group or belong to a certain religion or region to become a member. Extremist groups are motivated either by money or religious beliefs. In order to sustain themselves, financing often comes through illicit drug trafficking, arms trafficking human trafficking, bank robberies, kidnappings (ransom), and maritime hijacking. The difference between organized crime and violent extremism is at times difficult to discern.

In their 2017 study based on interviews with hundreds of voluntary recruits to Al-Shabaab and Boko Haram, the United Nations Development Program found that the journey to violent extremism is one marked by exclusion and marginalization, lack of opportunities, and grievances with the state. About 71% of those interviewed cited government action — the murder or arrest of a family member or friend — as the tipping point for joining a violent extremist group, indicating the limits of militarized counter-terrorism responses by governments. (Obonyo)

In 1994 the UN (UNDP Human Development Report, 1994) redefined security to embrace human rights and developmental perspectives. While the traditional definition was limited to physical threats, the new concept is broader, embracing the well-being of the population. Thus, the concept of security has moved from threat-centric to people-centric. The UN report stated that the concept of human security “has been related more to nation-state than to people ….in the final

analysis human security is a concern with human life and dignity.” (22) The people-centered concept of human security is different from the notion of state security, or from the security of the political elite. If economic growth does not improve the lives of the orderly people it is a violation of the security of the population and is to be considered either bad governance and at worse a criminal act. The so-called African economic growth is discussed in this context in this article.

As indicated on my website the growing nexus between organized criminal gangs and terrorist groups has turned Africa into a new theatre of violence and terrorism and disrupted attempts to improve the lives of the majority. The crisis created by the activities of organized criminal groups is one of the most serious challenges to regional and global peace, stability, economic development and peaceful co-existence. Weak governance and the absence of the rule of law, corruption and dysfunctional institutions, a vulnerable civil society, poverty and horizontal and vertical inequality, porous borders, radical interpretations of religions and other extremisms, have coalesced, leading to the rise of violent militant groups and criminal gangs. In many parts of Africa the absence of hope for a better future has created an uncontested environment for recruitment and indoctrination. The fate of several African countries hangs in the balance as conflicts ravage parts of the continent, mostly in the continent’s northern, western and central parts as well as in the Horn of Africa, but the threat is steadily spreading southwards.

The security threats posed by natural resources and the extractive industries, by climate change and by criminals and terrorists have the potential to destroy the integrity and legitimacy of the states and undermine their capacity to protect their citizens and implement sustainable economic development programs. But the reaction of governments to real or perceived threats (i.e., terrorism) can also undermine the security of its citizens in the form of human rights abuse and denial of constitutional rights. This fine line between the rule of law and authoritarian rule in the name of protecting the citizens has become the subject of great concern and debate in contemporary Africa.

It is the nexus between the various criminal activities across national boundaries and regional and global criminal networks and the potential access to the most lethal weapons of destruction that would force Africa to set in motion a fundamental departure from conventional strategies to combat these contemporary security challenges. There is no one holistic solution because the conditions that bring all the groups together are different. The real religious zealots are after state power, the criminal gangs are after money, the ethnic lords are after controlling resources and protecting their turfs, and for many it is simply the empowerment to do whatever they want with impunity. Whatever the motivation, the result has been death and destruction on a massive scale, causing the great majority of Africans to remain poor and insecure.

To be able to defend Africa from this looming catastrophe, AU member states will have to agree on a common strategic doctrine that addresses the root causes of violence, the proliferation of small and big arms, including weapons of mass destruction (e.g. bio-terrorism), and giving up some aspects of state sovereignty in favor of a common regional and international strategy. There is a desperate need in Africa for strong, selfless educated leaders with visions like their forefathers. (See main document for the Visions of our forefathers) No country can solve the problem on its own. Violent extremism does not have a country or a boundary. It is regional, continental, and global and has the capacity to corrupt governments and be a proxy to external agendas. Mr. Lapaque Pierre UNODC (UN Office on Drugs and Crime) regional representative for West and Central Africa emphasized, “The work of the civil society is crucial in addressing the problem of violent extremism. They provide a good understanding of the local realities, which is needed to devise effective polices in the region to fight against transnational organized crime and corruption.” (UNODC)

GDP and Human Security

The GDP as a measurement of human progress does not embrace human security in the sense that has ben defined above. These conceptual changes in the security debate happened primarily in countries undergoing change to make the concept of development broader and more inclusive. GDP does not measure the wealth of the people. It only measures the income that the state gets. It tells you the value of goods and services produced yesterday in a particular country not about tomorrow and not how the people benefited from it.

When Nigeria was busy selling high-priced oil to the world before the price crash, its GDP (money in the state coffers) was soaring. But its wealth was falling. “Oil deposits were used up, but cash was not reinvested in human, physical and technological capacities to ensure future income. Only wealth accounts could have drawn attention to that” (Pilling).

The fundamental impact of Africa’s economic decline or stagnation is shown by the increase in income disparity even though it is decreasing worldwide. This income inequality exists under all kinds of measurements, which clearly indicates that the states in Africa have become richer and rich citizens in all those countries labeled as the fastest growing economies have benefited more than poor citizens. “A prime example is Nigeria where the incomes of the poorest 80 percent of the citizenry have declined, while the incomes of the richest have increased. That situation provides little incentive for the rich and powerful to make meaningful policy changes”(Picker) and if I may add, Ethiopia is one in this category of deceptive growth measurement.

Despite the much acclaimed economic growth rate of Ethiopia over the last 20 years averaging 10.5%, which could be an economic miracle in the world, according to the Human Development Index (HDI) prepared by the United Nations itself, Ethiopia is actually one of the poorest countries in the world-number 173 out of 189. Most of the others are in Sub-Saharan Africa. (“2019 Human Development”)

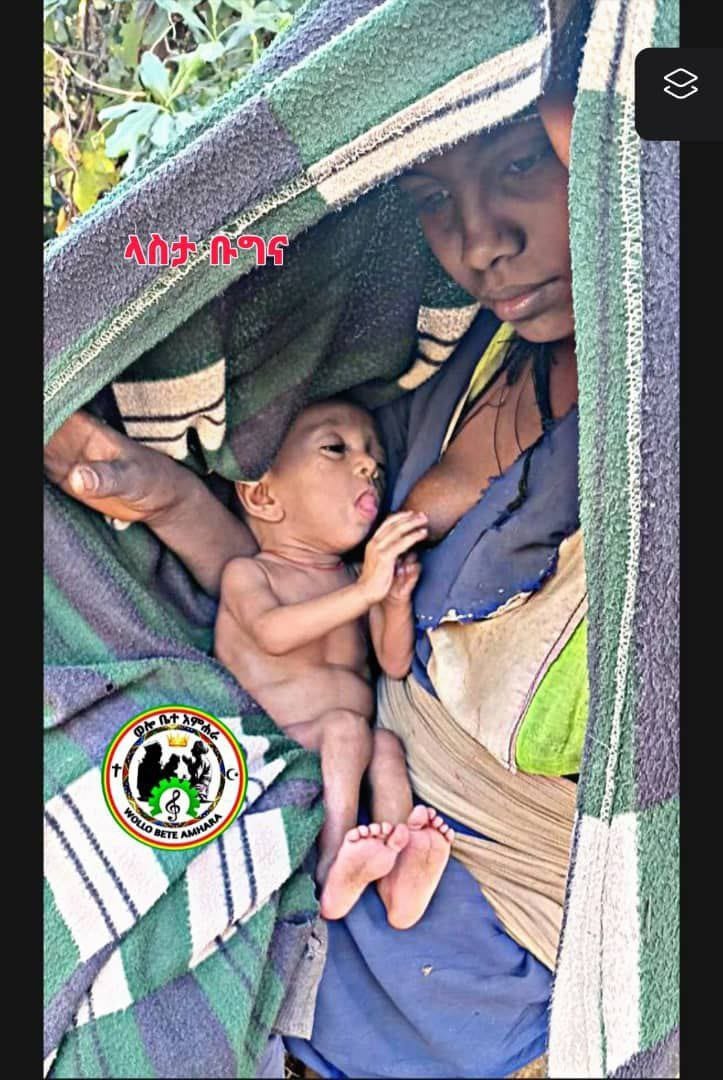

The Oxford Multidimensional Poverty Index measured by the proportion of the population that is multidimensional poor and the average intensity of their deprivation, ranks Ethiopia as one of those often viewed as emblematic of poverty with a very high index of 0.489 in 2020. This is calculated from both the percentage of people in poverty (83.5%) and the intensity of their deprivation (61.5% live in severe poverty). (“Global MPI Country Briefing 2020”).

The global burden of poverty is highly concentrated in Africa. For example, just two countries– Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of the Congo – have more than 150 million people living in extreme poverty according to World Data Lab during the time that Africa was dubbed as the fastest growing economy in the world. The World Data Lab also estimates that nearly 80% of countries that will be unable to eliminate poverty by 2030 are in Africa. “When weighted for absolute number of people living in poverty, that figure increases to more than 90%.” (Donnenfeld). It has already proved to be an impossible goal under any circumstances.

The major factor driving this increase in poverty is Africa’s rapid population growth. But another, which is more serious is human security, with Africa being the continent with the largest number of conflicts. Government revenues are spent more on state security rather than human security. People do not have the freedom to express opinions or move freely in the country without risking their lives. Government officials are corrupt. Public services are weak. There are parallel security forces, in some places warlords, who control people’s actions. In some places people are being killed, displaced, and harassed for who they are. Violent extremists have infiltrated many African countries and people’s lives are being controlled by the rules established by these criminal gangs. Violent extremism is spreading like wildfire across the continent and has become the major impediment to development. Africa is projected to decrease the proportion of people living in poverty by nearly five percentage points between 2015 and 2030, “But despite that percentage reduction, the absolute number of people living in poverty is forecast to more than double over that same period, swelling from around 270 million in 2015 to more than 550 million in 2030” (Donnenfeld). And these projections do not even consider the spreading violent extremism nor the impact of Coved 19, in 2020.

African Rise or Decline in Human Security?

Poverty, population displacement, hunger, disease, environmental degradation and social exclusion all directly affect human security. People live their daily lives based on people-centered, human concerns: their hopes and their aspirations for tomorrow, the desire to live in peace, dignity and freedom and to exercise their choices freely within the bounds of internationally accepted domestic laws, to live with opportunities and feeling confident of not losing them. In most of Africa these do not exist. Africa is at war with itself but it was not brought on by itself. If the conflicts we see today are the results of poverty then African countries should ask why they have become so poor when they own the resources now? If we are fighting because of lack of justice, equality, and freedom then African countries should ask themselves why did we create a political system that mis-governs, exploits and represses our people? If we are fighting because of ethnic and religious differences what we have to ask ourselves today is how did the 2000 ethnic groups of Africa live together relatively peacefully amongst themselves before and during the times of the colonizers? Something must have happened to make Africa today the continent with the largest number of conflicts.

The answer could be found in “the second scramble for Africa” which Julius Nyerere of Tanzania predicted. Poverty, migration, and the rise of transnational crimes and insurgencies and civil wars that led to continuous political crisis and regional instability on the African continent lie heavily on the shoulders of the African elites and the leaders. How then can we explain the fact that 94% of the UN peacekeeping missions, the largest and most expensive, are all in Africa?

Many of the missions on the continent are amongst the world’s most expensive and largest forces under the U.N. mandate. With the funding cutbacks by the U.S., many missions have to reduce operational costs and workforce. Is this a wake-up call to the African Union to get its act together? (Mbamalu).

The United States is the single largest financial contributor to UN peacekeeping activities. Congress authorizes and appropriates U.S. contributions, and it has an ongoing interest in ensuring such funding is used as efficiently and effectively as possible. The United States, as a permanent member of the U.N. Security Council, plays a key role in establishing, renewing, and funding U.N. peacekeeping operations. For 2020, the United Nations assessed the US share of UN peacekeeping budgets at 27.89%; however, since 1994 Congress has capped the U.S. payment at 25% due to concerns that U.S. assessments are too high. For FY2021, the Trump Administration proposed $1.07 billion for U.N. peacekeeping, a 29% decrease from the enacted FY2020 level of $1.52 billion (“United Nations Issues”). But peace has not come yet despite these efforts. There are several major trouble spots.

South Sudan is still fragile after civil war broke out in December 2013. Over 50,000 people have been killed—possibly as many as 383,000,—and nearly four million people have been internally displaced or have fled to neighboring countries. 2018 brought an increase in regional and international pressure on President Salva Kiir and opposition leader and former Vice President Riek Machar to reach an agreement to end the conflict, including targeted sanctions from the United States and a UN arms embargo. In March 2020 the Security Council Renewed the Mandate for United Nations Peacekeeping Mission (“Security Council Renews”).

In Sudan the Darfur situation is still not resolved. In June of 2020 the Security Council extended the deployment of the African Union-United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID) and set out the parameters for a follow- up mission that will start its work on 1 January next year. Somalia is still in turmoil and the Security Council has authorized the African Union to deploy its troops there in the run up to elections (“Security Council Reauthorizes”).

The Central African Republic (CAR), which has been in civil war since the overthrow of President Bozizé in 2013, is still in turmoil. There are over 13,000 UN troops deployed there currently. (“MINUSCA”)

According to International Peace Institute Global Observatory “For instance, the UN at present has seven multidimensional peace operations deployed on the continent (one deployed in partnership with the AU), as well as three special political missions that play the role of multilateral peace operations (one of them being mandated to support an AU mission). The AU currently has five operations deployed in Africa, including the largest peace operation in the world in terms of number of uniformed personnel deployed: the African Mission to Somalia (AMISOM). In addition, Regional Economic Communities (RECs), Regional Mechanisms (RM), as well as ad hoc security initiatives currently deploy another five operations in the continent.”

The presence of UN and African Union Peacekeeping Missions in so many countries shows the extent of instability that warranted UN and AU intervention. In most of the African countries where the UN has been for years the peacekeeping missions have not resolved the root causes of the conflicts and have not been able to make the necessary changes in policies and governance to ensure sustainable peace, because they had limited mandates to do this. That is why year after year they request the extension of the presence of the UN. There are even more countries in Africa with very serious internal conflicts and cross-border security issues that have not been considered for UN interventions partially because the governments refuse to internationalize their countries’ problems. Ethiopia seems to be going along this path with civil war raging in the North and Southwestern part of the region. We have yet to see where the government will be able to stabilize the fragile security situation that is fast becoming a concern to regional peace and stability perhaps requiring UN intervention. We hope it will not reach that stage because if it does it will be a major set back to world and regional peace.

Salafism (Wahhabism) and Conflicts in Africa

The contemporary challenges of Africa for the last two decades have come from extremists, who have spread across the globe after the 911 attacks and the Arab Spring. There are no major extremist organizations operating in the Arab World or in Africa that do not have direct or indirect support and inspiration from the Wahhabi /Salafist government of Saudi Arabia. One cannot explain Salafism without looking into Wahhabism. This ultra -conservative interpretation of Islam is based on the teachings of Muhammad Ibn Abd al-Wahhab who together with the Saud family created the country called Saudi Arabia. The Arabian Peninsula was then under the control of the UK who, in effect, allowed this country to come into being through an agreement with Abdul Wahhab and the Saudi family. In the current discourse on Islam, the term “Salafi” and “Wahhabi” are often used interchangeably. Many confuse the two while others refer to them as one. In effect they are two faces of the same coin. The Wahhabis are always referred to as Salafis, and in fact they prefer that term. As a rule, all Wahhabis are Salafis but not all Salafis are Wahhabis. The term Salafism did not become associated with the Wahhabi creed until the 1970s. It was in the early 20th century that the Wahhabis began to refer to themselves as Salafis.

Wahhabism is likely to remain a pillar of the kingdom in the medium term. The religious establishment controls colossal material and symbolic means — schools, universities, mosques, ministries, international organizations and media groups — to defend its position. Any confrontation between the descendants of Saud and the heirs of Ibn Abd al-Wahhab will be destructive for both.

The historical pact between the monarchy and the religious establishment has never been seriously challenged. It has been reinterpreted and redesigned during times of transition or crisis to better reflect changing power relations and

enable partners to deal with challenges efficiently. In fact, Saudi export of Wahhabism was first used to counter Egypt, which was seen as the leader of the Arab world under Nasser. Nasser’s anti-imperialist stand helped Saudi Arabia advance a religious revival in the Muslim world.

The Wahhabi strategy was deployed to fight the Soviet Union. The mobilization of the mujahedeen in Afghanistan was a classic example of this. This is where western powers were most complicit in training so-called ‘religious warriors’ to fight the Soviets. It will be recalled that Pakistan too became a willing western pawn in this regard and helped the Afghan mujahedeen. That decision in turn saw the rise of religious extremism in Pakistan, leading to the situation Islamabad finds itself in today. That was where Osama Bin Laden’s strength grew to become one of the fiercest challengers of the Soviet Union and then America.

Wahhabism is now being used to combat Shiism (Shia), which has gained in prestige and power since the Islamic Revolution in Iran in 1979. Saudi rivalry with Iran on the leadership of the Muslim world is now perceived as the most serious challenge wherever Muslims live. The destruction of Yemen is a proxy war between Iran and Saudi Arabia and its allies. Fundamentalist strains of Islam, including Saudi-born Salafism and Wahhabism, form the ideological bedrock for most terror groups according to a study by Leif Wenar of King’s College London. Three out of four terrorist attacks in the last 10 years have been inspired by Salafism (Solomon). Leif Wenar of King’s College London states that

Saudi Arabia is the chief exporter of Salafism around the world, spending tens of billions of dollars to build mosques, fund madrassas, finance preachers and offer scholarships to students to study the rigid form of Islam. The effort is possibly the most expensive ideological campaign in human history.

Saudi Arabia is not the only factor, of course, in the spread of violent extremism. But for 50 years Saudi Arabia has been funding schools and mosques and radical preachers worldwide who have set down their particular narrow and puritanical version of Islam, which has in many places mutated into the violent extremism we see today (Solomon).

The problem of jihadist terrorism is not going away any time soon. It has been almost 20 years since 9/11 and despite the efforts of the United States and other countries the extremists are still very much a threat as a recent article in Foreign Policy made clear:

Here’s a sobering fact: Even after the destruction of the Islamic State’s territorial caliphate in Iraq and Syria, there are today more jihadist or criminals fighting in more countries than there were on Sept. 11, 2001… The harsh reality is that despite the United States’ important successes in killing terrorists on the battlefield and preventing another 9/11-scale attack, the problem of radical Islamist terrorism is not shrinking. On the contrary, it has steadily morphed and metastasized. After nearly 18 years, and enormous expenditures and loss of life, the United States still has no proven strategy for reducing the number of young people around the world susceptible to jihadists or criminals in the name of Jihadism. It’s been clear to U.S. policymakers for years that hard power alone— military action to kill terrorists and disrupt terrorist plots—is not by itself a winning formula. While necessary for long-term success, hard power on its own is simply insufficient. Also essential is a strategy for combating the extremist ideology that serves as the central building block of jihadism—the totalitarian, intolerant, ultraconservative interpretations of Islam that systematically dehumanize all those holding different beliefs, both Muslim and non-Muslim alike. Killing terrorists has proven a relatively straightforward task. Killing the state of mind—the idea that helps radicalize and then, in far too many instances, weaponize young Muslims to kill nonbelievers—has been a vastly more difficult undertaking. (Hannah)

It should be recognized that the spread of these extremist views are facilitated by a systematic educational approach of religious leaders funded by enormous oil wealth of the kingdom.

The universities of Islamic studies are another key vector of Saudi Arabia’s influence through the religious sphere. The Islamic University of Medina, the Umm Al -Qura University in Mecca, and Imam Muhammad in Saud Islamic University in Riyadh have been training thousands of imams and ulamas through scholarships since the 1970s. The latter, once they have returned home, not only practice Wahhabi Islam in mosques that are often built with money from Riyadh, but also have a strong attachment to the Kingdom that trained them. Nowadays, this clergy that has been molded for three decades in these universities, occupies the highest religious positions in Africa and has some influence over their country’s political authorities (Auge).

The Wahhabi influence has also been increasing through schools for children, cultural centers, mosques, and charities. In a 2013 report Saudi Arabia provided as much as 10 billion dollars to promote Wahhabism through charities, some with ties to terrorists (Palazzo). Millions of dollars from charities goes to Africa, for example, the King Faisal Foundation has 197 projects, 43 of them target Africa (Auge).

Saudi Arabia has put a policy in place linking diplomacy, financial aid and the politicization of Islam in order to have influence in Africa. Although, its objectives have not always been achieved … however, it has built a solid network of alliances, particularly in the Sahel and the Horn of Africa. It is mainly through official state channels that Riyadh’s power in Africa is deployed, since the private sector’s economic initiatives are still very modest. The men in the background and other intermediaries, although they obviously exist, are not the kingdom’s main vectors for African policy, which can count on an experienced administration. Saudi Arabia does not seem to consider Africa as a projection area for its economy. Its investments there still remain undisclosed compared to donations and partnerships operating with money from the zakat (alms-giving) (Auge).

The most dominant and influential extremist ideology in Africa has never been ISIS but its derivative and source the ultra-conservative ‘Arab-infused Wahhabi model of Islam’ that is being spread by Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States. With the enormous amount of wealth hey have and investment on mainstream and social media globally they have been able to change mindsets of millions of vulnerable Africans. The most dangerous violent extremist groups, Boko Haram and al-Shabab were created re ISIS. The leader of Boko Haram, Abubakar Shekau, in his own words, was trained n Saudi Arabia. Al-Shabab advocates taking political power by force and practices Saudi inspired Wahabism while most of Somalis are Sufis.

The extremist groups across Africa, which had different names before, are now adhering to the new brand of Islamic State and have become the major destabilizing factors on the continent that have hindered development and social harmony. They have promoted conflict between Christians and Muslims and even amongst Muslims.

The Mozambican Islamic Insurgency in the northern province of Cabo Delgado, Muslim extremists have become increasingly active, with the usual atrocities, abductions, and arson associated with jihadists. This is the most surprising security development in Southern Africa, so far considered the most unlikely place for extremists insurgencies and first manifestation of a militant movement which is directly associated with the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, and the notion of a jihadist insurgency.

“The ongoing conflict in northern Mozambique has gathered pace over the past several months and shows little sign of abating, despite the Mozambican military and Russian private military contractor (PMC) Wagner’s security operations in the region. Islamic State Central Africa Province (IS-CAP) has claimed responsibility for attacks at an increasing rate over the past six months, but the dynamics between various militant cells in the region remain opaque. While the dynamic between local cells in Mozambique is still unclear, there have been mounting indications as to what IS-CAP’s overall structure will look like and the logic behind its geographic layout.”(Perkins)

The major groups operating in Africa are the following:

The Islamic State in Sinai (Ansar Beit al-Maqdis), Islamic State in Egypt (IS-Misr), IS in Algeria (ISAP), Islamic State in Libya, Boko Haram in Nigeria, Boko Haram in Cameroon, National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) in Mali, Islamic State in Somalia, al-Shabab, IS in Tunisia, Islamic State in Central Africa Province (ISCAP), Mozambique, Democratic Republic of Congo and Tanzania, Islamic State in Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. The details of these are in main document of this research work. Below I will discuss the development in Greater Horn of Africa.

The Islamic State in Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda

“In April 2016, a grouping called the Islamic State in Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda (ISSKTU), or Jabha East Africa, pledged loyalty to al-Baghdadi, though again, the pledge was never recognized. A breakaway from al-Shabaab, the group was formed by Mohamed Abdi Ali, a medical intern from Kenya who was arrested in May 2016 for plotting to spread anthrax in Kenya to match the scale of destruction of the 2013 Westgate Mall attacks. As its name suggests, the group—small as it is—has a multinational composition.” This is a small group and may have ceased to exist (Warner and Hulme).

Al-Shabaab operating out of Somalia remains the largest and deadliest terror organization in East Africa, according to Africa Command. The extremist group was responsible for a truck bombing in Mogadishu in October 2017 that killed 500 people in one of the deadliest violent extremist attacks since September 11, 2001. More recently, it was responsible for an attack in January on a hotel complex frequented by Westerners in Kenya’s capital city that left more than 20 innocent people dead. Poverty and hopelessness has driven many Kenyans to cross the border and join Al Shabaab in neighboring Somalia.

For the past decade, Al Shabab has targeted marginalized communities along East Africa’s Swahili coast who share historical ties through Islamic culture and ancient trade roots. Khelef Khalifa, a veteran human rights campaigner and Chairman of Mombasa-based Muslims for Human rights (MUHURI) told TRT World that Kenya’s raging financial turmoil and erratic economy is “causing unemployment and pushing desperate youth to join militant group, Al Shabab”. Rampant corruption and a judicial crisis have fueled the militant recruitments. For decades – even before 2013 when devolution came to effect – resource allocation was skewed which resulted in the marginalization of some areas. An effect that is still being felt to date.

“The extremists are promising hefty pay for local fighters who have largely remained unemployed or poorly paid,” Khalifa said. “They target those below 30 years, Kenya’s biggest population and one which has been greatly affected and impacted by unemployment.

“Al Shabab is waging more terror onslaughts in Kenya than any other radical faction in the world. Al Shabab came into existence in 2006 as an armed wing of Islamic Courts Union, later splitting into smaller groups,” Khalifa said. “At the time, youth unemployment in Kenya was at around

22 percent according to data from Statista – a reputable international firm leading in providing market and consumer statistics. Al Shabab attacks increased with the rate of youth unemployment.” (“Why Is Al Shabab…”)

Islamic State In Ethiopia

Islamic State militants in Somalia say they will release jihadist materials in Amharic — a step unmistakably aimed at winning recruits in restive, neighboring Ethiopia. The announcement came in the form of a three-minute video released last month by pro-Islamic State sites and endorsed by the official IS media. The video posted the words to one of Islamic State’s best-known chants in Amharic and promised IS will release more materials in the language, one of the two most-spoken tongues in Ethiopia.

Matt Bryden, an Africa analyst with Kenya-based Sahan Research, believes Islamic State — also known as ISIS — is reaching out to Ethiopia’s Muslim community in an attempt to take advantage of ongoing ethnic and political unrest in Africa’s second most populous nation (Maruf).

An Ethiopian army official, Colonel Tesfaye Ayalew, gave further details on September 11 of Ethiopia’s recent arrest of Islamic State militants in the country. Ayalew said that the arrests took place in towns near the Kenyan and Somali borders and that the majority of Islamic State militants arrested were Syrians and Yemenis, although Ethiopians were arrested as well. The colonel attributed the arrests to Ethiopia’s strong relationship with the Somali Federal Government (SFG).

SFG Prime Minister Hassan Ali Khaire visited Somali National Army (SNA) troops in Hudur town, the capital of Bakool region in Southwestern Somalia, on September 12. Khaire urged SNA forces to liberate areas still under al Shabaab control in the region (Barnett and Larsen). Pro-Islamic State militants in Somalia reported the death of an Ethiopian jihadist among their ranks, but the group didn’t say when/how he died. Abu Zubayr Al -Habash appeared in IS video in Dec 2017 threatening attacks on public places in Somalia (Maruf). Sixteen members al-Shabab ad 17 members of IS were arrested in 2019; 2020 (33 members in one year). In the middle of November 2020, the Ethiopian government announced that 14 IS insurgents have been captured. It further explained that these people had the intention to create mayhem in the capital. These of course are ominous signs of difficult times ahead. With the war the government has begun with Tigray, cracks are going to be opened for insurgents to be activated under the cover of the war. Such wars are the traditional fertile grounds of violent extremists.

In the summer of 2020 Ethiopia was shaken by massacres of Christians and Amharas at the hands of Oromo Islamic extremists. These were a landmark events that took Ethiopia into uncharted territory in Muslim – Christian relations. It was by all accounts a well -organized operation implemented a few hours after the assassination of the famous Oromo singer and activist, Hachalu Hundessa, who himself was a Christian. It is not yet clear who killed him, but in the anger, unrest, and protests that followed, hundreds of Christians were massacred. The killers seem to have come from the ranks of those gangs of young men called querros who have been organizing for years. Understanding who the querros are, what they want, and how they are organized reveals a complicated picture, but they are forces to be reckoned with in Oromia, and because of the large number of unemployed young people, Muslim extremists find a ready-made audience for their aggressive politics of destruction.i

The incidents that took place following the assassination were unprecedented in Ethiopian history, both in the manner in which they were carried out and in the

number of victims who died and were tortured, all accompanied by appalling messages of hate and disgusting slogans. These events filled every Ethiopian with revulsion, both Muslims and Christians, who never had this sort of conflict in their recorded history. Islam and Christianity were introduced in Ethiopia long before they reached much of the Middle East, North Africa, Europe and the rest of the world. Ever since they have peacefully co-existed.

In the past three decades history has been manufactured to fit the Wahhabi agenda of politicizing Islam and creating Islamic government in Ethiopia. Saudi Arabia and its allies and surrogates have trained many Ethiopians in the various madrassas in Saudi Arabia, in Pakistan and Sudan, one of which I have visited. Ever since, we have been seeing cracks in the cooperation that has been there for many years. Extremists always choose time and place to create instability in a country. This time they took advantage of the political instability that existed in Ethiopia and the open hostility between the Amharas and Oromo nationalists in which the political leaders have played no positive role. These sorts of crimes that have been committed against Amharas, the Orthodox churches and their followers in the last two years, since PM Abiy came to power were unheard of. Some of the crimes directed against Amharas and those belonging to the Orthodox church can only be termed as genocide in its precise definition. It resulted from the policy of the previous government, an ideology of hate embraced openly by the very party that the current PM belongs to. He never tried to change it. To make matters worse the PM did not express his condolences to the hundreds of Amhara, Christians, Welayitas, and Gurages that have been murdered tortured and displaced. This reinforced the suspicion of many that had doubted the sincerity of this PM to bring peace to Ethiopia. It seems that he is either a member of this extreme nationalist Oromo movement, who are anti -Amhara and anti-Christian, or he has been become a captive of these forces. Time will tell.

What gives me hope are the words of Desta Heliso, an Ethiopian professor of theology:

…, I do not think that the dream of Islamic extremists to establish a political government, which sustains puritanical Islamic doctrine through a strict application of Sharia, will come true in Ethiopia. But any success of a fundamentalist form of Islam in any part of the country could lead to religious conflict and potential disintegration of the country. That will probably end any hope of peace and stability in the Horn of Africa. So I urge all those who focus on the imperfections of the current system and the failures of the current government to consider this issue as well. Our deep and legitimate desire to perfect the democratic process and bring about the sort of ‘human-rights’ we have experienced in the West should not blind us to one of the greatest threats Ethiopia (and the world) is facing right now. Without safeguarding the secular state and developing strong security, religious extremism cannot be tackled. If religious extremism is not properly tackled, democracy and freedom cannot be achieved or protected.

In his very profound research work under the title “Islam, the Orthodox Church and Oromo Nationalism” Abbas Haji Gnamo defines the historical roots of both religions and the dynamics between people of various religions in Ethiopia and concludes that these relationships have been based on tolerance and a full sense of belongingness to one country with mutual aspect and equality. I hope such sincere intellectual voices would prevail and prevent Ethiopia from descending into the chaos of ethnic conflict that we have seen in so many other African nations.

Muslims, Christians and traditional believers fully share the core idea of Oromo nationalism. This would entail that the path of Oromo nationalism is founded on twin policies: secularism and tolerance. Strict respect in religious matters does not only aim to maintain the harmony of the Oromo but also to define their national identity in an open and inclusive way due to religious differences among the Oromo themselves. Religious tolerance or accommodation of differences is not new to Oromo worldview/cosmology. Despite this, there are some individuals who try, from within or without, to divide the Oromo, along religious/confessional lines or politicize religion….

- a systematic application of the Wahhabi tradition of Islam into non-Arabic culture poses a series of problems. In effect, if African Islam, perhaps in other cultural areas as well, easily expanded and got many followers it was mainly because it managed to adapt itself to local cultures and incorporate some rituals, beliefs and other traits of culture, by Islamizing them, although the acceptance of its basic dogma is a prerequisite to be Muslims (Tapiéro 1969: 74). Popular Islam in many respects is certainly in contradiction with the Puritanism of Wahhabi tradition (Abbas Haji Gnamo).

While the theory seems to support an unlikely scenario of wide spread Wahabi(Salafi) movement in Ethiopia, the realities on the ground are different. The cracks in the fabrics that had for long united all sectors of Ethiopian society (religious and ethnic) are getting wider, because of war, poverty and insecurity, making it possible for extremist operators to recruit and mobilize followers with relative ease. The rise of terrorism and violent extremism across Africa is attributable to the weakness of the states. Extremism preys on fragile states and fuels violence and instability towards an uncertain political objective. Ethiopia is certainly in that category.

Conclusion

Though the TPLF leaders whom most Ethiopians have demanded that they be brought to justice have not yet been captured, the TPLF force has been irreparably crushed. The center has asserted its power as it should have done from the get go. There cannot be a country without a center. TPLF defied this basic commonsense. Ethiopians want to see a center that crushes all those who resort to violence and that addresses the central issue of democratizing Ethiopia, where ethnicity does not infringe on the inalienable rights of people to be equal under the law. This would mean changing the constitution, delegitimizing ethnic federation, and electing its leaders through a fair and free election under a transitional government that would not interfere in the shaping of the constitution and running of the election.

For once, let the people speak! What is needed in Ethiopia is a devolution of power under a non-ethnic based federal system which will assure people that, despite their ethnic backgrounds, they will all be Ethiopians first, and own the country together. Genuine “Truth and Reconciliation“ and the eradication of distorted history through dialogue and education would slowly but surely bring back Ethiopia where it belongs — the “Hope and Vanguard of Freedom”, as it has always been and told by blacks and other oppressed people across the globe for centuries.

Violent extremism can be fought back and the challenge of “Human Security” can be addressed successfully only in peace and unity. Ethiopians should remember that they have a country that is extraordinarily beautiful and having an unparalleled history, but a country in one of the most complex security and militarized zones in the world. Being seen as a weak state will invite many kinds of enemies. Let our leaders be bold enough to pave a path to a strong Ethiopia by making the necessary fundamental changes now before it is too late. If the Ethiopian leadership can crush one of the staunchest enemies of peace and unity in our history, then it can easily crush the OLF and other extremists. Both OLF are TPLF fulfill the requirements of being designated as terrorist organizations, dangerous not only to peace and security in Ethiopia but to the region. According to the policy memorandum of US Immigration Services of June 15, 2014: “the TPLF qualifies as a Tier III terrorist organization prior to May 1991”, that is, until it became the government. Now that it is waging war against its own people it should be re- designated as a terrorist organization. Oromo nationalists have inherited the ideology and practice and implementing it more intensely and aggressively than the TPLF. There will be no sustainable peace unless it too is crushed in the same kind of determination. Amharas have proved once again that they will be with any government and any leader that has the interest of a united, equal, just and free Ethiopia first.

Listen to this : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LgoW4GMlftA

END

*References are to be found in the main document: www.africaisss.org

Dawit W Giorgis Executive Director of the he Africa Institute for Strategic and Security Studies and visiting scholar at Boston University, African Studies Center.