Oct0ber 16, 2020

Nawaid Anjum

Hindustan Times

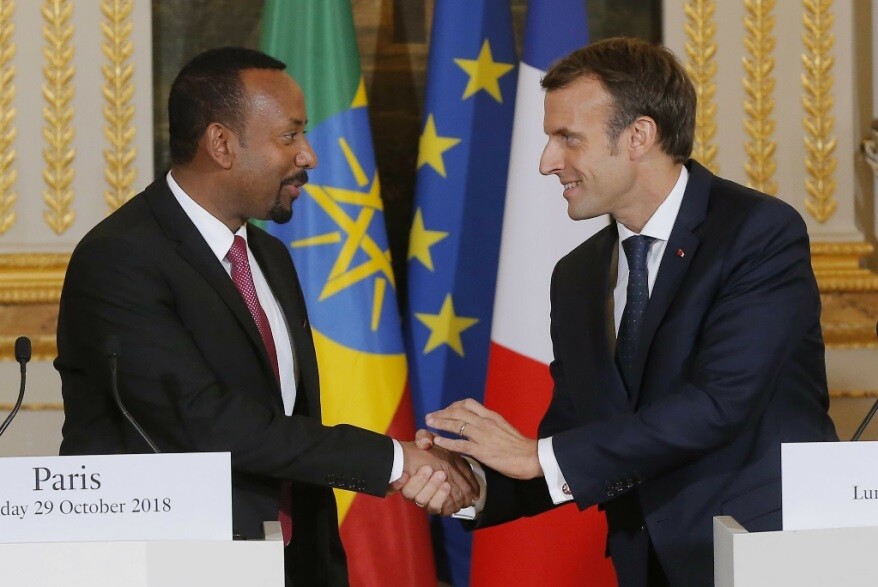

A woman veteran of the Italo-Ethiopian war in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, on November 30, 2019. (Eric Lafforgue/Corbis via Getty Images)

Maaza Mengiste talks about her Booker-nominated novel, The Shadow King, a story about women at the forefront of war during Benito Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935.

Memory and history are two favourite territories of Maaza Mengiste, the Ethiopian-American novelist and essayist, whose second novel, The Shadow King has been shortlisted for the 2020 Booker Prize. Mengiste, 46, who has mined Ethiopian historical memory in her works, including her debut novel, Beneath the Lion’s Gaze (2010), is interested in the stories of ordinary people in the footnotes of history, those often omitted from official archival records.

The Shadow King, which will soon be adapted for a film by Kasi Lemmons, received its share of praise long before the Booker nomination. Salman Rushdie lauded it for “lyrically lifting history towards myth”. Former Booker winner Marlon James wrote that the novel’s women “will slip into your dreams and overtake your memories”. Though this story about women at the forefront of conflict is set during Benito Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 and much of its action takes place just before and during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, the novel begins and ends at the train station in Addis Ababa in 1974. With the war raging in the backdrop, Ethiopia’s collective memory is threatened in the wake of the Italian invasion. Two women — Hirut, an orphan who, early in the novel, struggles to adapt to her new life as a maid, and Aster, the wife of her employer, an officer in Emperor Haile Selassie’s army — emerge as the nation’s saviours exhorting other women to take up arms and, eventually, steering Ethiopia towards a surprising victory.

Mengiste says she grew up on stories of women’s bravery, defiance, courage and determination. “They shaped how I imagined myself in the world,” she says. These stories had a common denouement: the victory of Ethiopia, which was poorly equipped and unlike Italy, the European colonizing force, not militarily and technologically advanced. “The victory established an identity for Ethiopia,” says Mengiste, for whom writing a book about what it meant to be a woman at war felt like the “natural direction” to go in. However, the author did not realise the extent of women’s involvement in the military until she started her research. “It was not easy to discover. It was history that was hidden,” she says.

During her research, Mengiste discovered that the archives had a particular perspective — they showed the way Italy wanted to remember itself. Scholars and writers hope to gather knowledge and gain perspectives on the narratives of the world through archival material. But Mengiste’s research made her wonder if searching in the Italian archives could ever help her arrive at any semblance of truth or balance. “Archives are not innocent. History is not naive. Museums are not neutral territories,” she says, underlining how the first draft of the history of the peoples of Africa, Asia, and every non-Western region has been written by Westerners as a way to remember themselves. “When we come in, our job is to look at the first draft and begin to edit. My dream is that one day we create the first drafts of ourselves. That is waiting to happen,” says Mengiste.

History may provide her with the backdrop, but the story, she says, comes from something different. Having the historical background is like having an event for the novel. But where is the story? “I realised that the closer I looked at women, the more I began to understand the many different battles that they were fighting; the conflicts were on the battlefields, but they also happened in the military camps. Women had to contend with multi-layered violence; there is fighting as soldiers, but there is fighting as women whose bodies are imagined to be the territories for their compatriots,” she says, adding that this has always been happening. This is the history of the world. And it is this that seemed to her to be the story. “Once I started focusing on women, I started imagining the way this would unfold and play out amongst different characters,” she says.

In contrasting the worlds of Aster, who is born into nobility and Hirut, born dirt poor, Mengiste’s idea was to explore what would happen if there was an uneasy alliance between two women of different social classes in the feudal social setup of Ethiopia of 1935, which was deeply divided by class.

Mengiste wanted to open the novel in 1974, almost 40 years after the end of the war, because she was curious about what remains after conflict — how much of our pasts do we really carry with us and how much can we let go? As a novelist, she says she is interested in the aftermath — what happens after big historical events. “I also had questions about forgiveness; and the way Hirut should or could forgive what the times did to her,” says the author. 1974 also marked the beginning of the Ethiopian revolution that would depose Emperor Selassie. “His rule in the decade determined why he was dethroned in the Seventies. I wanted to show a continuum, but I was also curious about how Hirut might change over the years and what she still kept with her,” says the author, who is also a filmmaker. In her writing, Maaza Mengiste keeps returning to the idea that we are made up of our memories. “That’s the cumulative force that guides us through our lives,” she says.

http://zehabesha.com/the-second-italo-abyssinian-war-1935-1936/