The United Nations has expressed concern about possible war crimes ahead of a threat by the Ethiopian army to start an assault on the northern Tigray region’s capital.

Fighting between Ethiopia’s central government and forces in Tigray has been going on for almost three weeks.

Hundreds have reportedly been killed and tens of thousands have fled.

Aid groups fear the conflict could trigger a humanitarian crisis and destabilise East Africa.

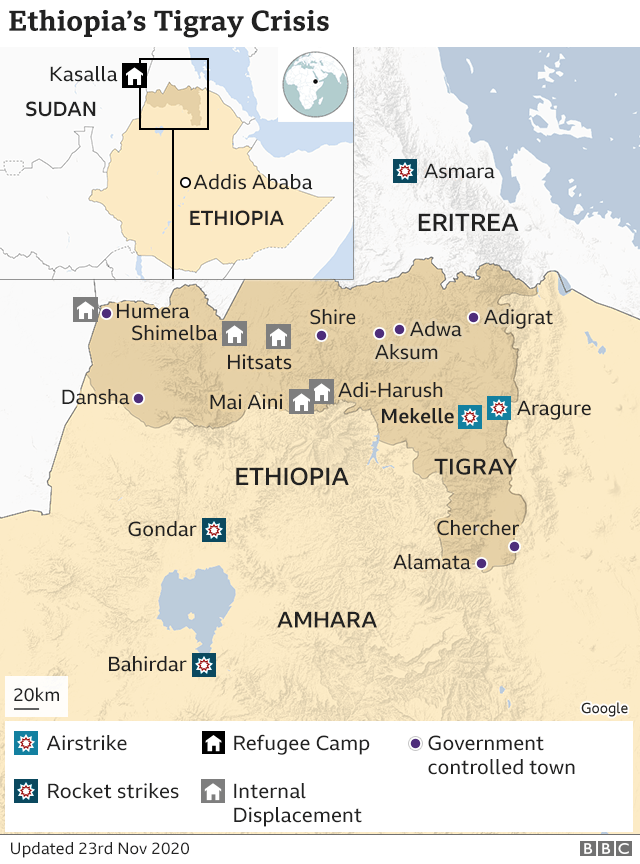

The UN said it was alarmed by the threat of major hostilities a day before the Ethiopian army said it would advance on Tigray’s capital Mekelle, home to about 500,000 people.

On Sunday, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed issued a 72-hour ultimatum to Tigray’s forces, telling them to surrender as they were “at a point of no return”.

But Tigray’s forces have vowed to keep fighting, with their leader Debretsion Gebremichael saying they were “ready to die in defence of our right to administer our region”.

Meanwhile, Ethiopia’s state-appointed Human Rights Commission has accused a youth group from the Tigray region of being behind a massacre earlier this month in which it says more than 600 civilians were killed.

The commission said the group stabbed, bludgeoned and burned to death non-Tigrayan residents of the town of Mai-Kadra with the collusion of local forces.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTREUTERS

IMAGE COPYRIGHTREUTERSHuman rights group Amnesty International first highlighted reports of a massacre in Mai-Kadra, but was unable to confirm who was behind it, or exactly how many died.

The Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), a political party which controls Tigray, denied involvement, and called for an independent international investigation into the killings.

The conflict started after Ethiopia’s central government accused the TPLF of holding an illegal election and attacking a military base to steal weapons.

In response, Mr Abiy – a former Nobel Peace Prize winner – ordered a military offensive against forces in Tigray, accusing them of treason.

The TPLF sees the central government as illegitimate, arguing Mr Abiy does not have a mandate to lead the country after postponing national elections because of coronavirus.

What did the UN say?

Michelle Bachelet, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, expressed “alarm at reports of a heavy build-up of tanks and artillery around Mekelle”.

She called on all sides to give “clear and unambiguous orders to their forces” to spare civilians.

“The highly aggressive rhetoric on both sides regarding the fight for Mekelle is dangerously provocative and risks placing already vulnerable and frightened civilians in grave danger,” Ms Bachelet said. “I fear such rhetoric will lead to further violations of international humanitarian law.”

The rhetoric has been ramped up in recent days. On Sunday, the Ethiopian army said “there will be no mercy” for Mekelle’s residents when its soldiers “encircle” the city.

Such talk could constitute a war crime, Ms Bachelet said.

Mr Abiy has repeatedly said the Ethiopian army would protect civilians in its campaign against forces in Tigray.

But Ms Bachelet said a virtual communications blackout in Tigray was making it difficult for the UN to monitor the human rights and humanitarian situation.

“Reports continue to emerge of arbitrary arrests and detentions, killings, as well as discrimination and stigmatisation of ethnic Tigrays,” the UN said.

The UN Security Council is due to hold its first meeting on Tuesday to discuss the fighting in Tigray.

At least 40,000 refugees have already crossed into neighbouring Sudan. The UN refugee agency has said it is preparing for up to 200,000 people to arrive over the next six months if the fighting continues.

Families torn apart as refugees flee across the border

A couple sit looking pensive by the wall of the UN building in Hamdayit in eastern Sudan’s Kassala region.

Smoke rising from a charcoal burner partially blurs their faces. The woman lines up tiny cups as she waits for coffee to boil in an earth kettle.

A traditional coffee ceremony is performed even in the worst of circumstances.

They’ve recently arrived at the transit camp, having fled from Tigray.

A young man interrupts this moment when he walks up to me. He worked as a customs official in the Tigray town of Humera but fled three days ago, he tells me.

I ask why he hasn’t yet moved to the refugee camp further away from the border. “I am waiting for my family,” he says.

They are still trapped inside Tigray. Families have been torn apart by the conflict.

What is the fighting about?

The conflict is rooted in longstanding tension between the TPLF, the powerful regional party, and Ethiopia’s central government.

When Mr Abiy postponed a national election because of coronavirus in June, relations deteriorated.

The TPLF said the central government’s mandate to rule had expired, arguing that Mr Abiy had not been tested in a national election.

In September the party held its own election, which the central government said was “illegal”.

Then, on 4 November, the Ethiopian prime minister announced an operation against the TPLF, accusing its forces of attacking the army’s northern command headquarters in Mekelle.

The TPLF has rejected the allegations.

Its fighters, drawn mostly from a paramilitary unit and a well-drilled local militia, are thought to number about 250,000. Analysts believe the conflict could be long and bloody given the strength of Tigray’s forces.