The Ethiopian elections are an imperfect step in the right direction

June 20, 2021

on June 21, Ethiopians will go to the polls for the country’s sixth general elections

We have been here before. The 2005 election was arguably the first one in Ethiopia’s history that saw meaningful political competition, and the party I led at the time achieved a significant showing. However, in the end, it was a missed opportunity. The government rejected the results and targeted its critics, and I spent over three years as a prisoner of conscience, separated from my young child and often in solitary confinement.

The election on June 21 gives new life to an old hope. But getting to this point has not been easy. Widespread protests in 2018 ushered in the promise of a transition towards a more democratic system, but the global pandemic forced a postponement of the elections scheduled for August 2020. The National Elections Board of Ethiopia (NEBE), which I chair, is the institution solely in charge of administering all elections in the country—but it has needed extensive institutional reforms, which we have been implementing while preparing for the largest election in Ethiopian history.

Our determination to include political parties in exhaustive consultations with the NEBE may have slowed the process, but it has built trust in our institution. When disagreements emerged between political parties and the NEBE, parties took their complaints to the courts rather than the streets. NEBE’s acceptance of court rulings has further built trust. This triple burden—of planning and reforming and trust-building—has been at times overwhelming, but it has been a necessary journey.

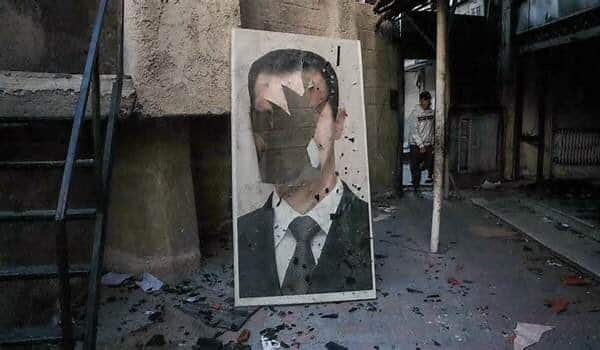

Still, Monday’s election is beset by other, serious challenges. Despite sincere efforts by myself and my colleagues to level the playing field, candidates and supporters faced restricting challenges in parts of the country, and our nascent democratic culture needs more work. As an example, a political party withdrew from the race, citing intimidation. Insecurity, malfeasance, and logistical challenges witnessed in parts of the country mean that voting in those affected areas will take place at a later date. And due to the violent conflict and crisis in Tigray, citizens in that region will not go to polls on June 21 either.

Against this backdrop, many have questioned the value of this election.

But despite the risks, progress—however imperfect—towards genuine democracy ultimately offers the best hope for enduring stability and peace in Africa’s most populous country and in the wider Horn of Africa region. And the best hope for the resolution of Ethiopia’s challenges, including the tragic Tigray crisis, is accountability through periodic, inclusive, and credible elections. This hope demands that we stay the present course and nurture nascent democratic practices and institutions. We cannot let the perfect be the enemy of the good. There are forty-six political parties and over 9,000 candidates competing in this election—more than in any previous process. Their commitment to the process, however imperfect, demands our support for the process in response. It is my strong expectation that for the first time in Ethiopia’s history, diverse and multiple political parties from across the political spectrum will take their seats in Ethiopia’s national and regional parliaments.

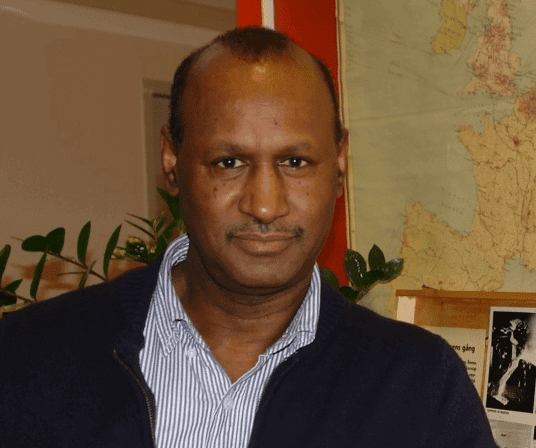

Birtukan Midekssa has been the Chair of the National Election Board of Ethiopia since November 2018; she is a former opposition leader and prisoner of conscience.