Flouting Ethiopia’s Sovereignty, Impeding Development, and the Italian Invasion in 1938

By Yosef Yacob (PHD)

Lake Tsana Reservoir Project Negotiations

Following the death of Emperor Menelik in 1911, British interest in the waters of Lake Tsana remained in abeyance. In May 1914, Kitchener reported that there was a possibility that the Abyssinian Government, owing to financial difficulties, would be willing to negotiate a definite treaty for the control of the waters of Lake Tsana and the Blue Nile. Kitchener sent with his dispatch a draft showing the form such a treaty might take.

The treaty proposed an option similar to that proposed by Lord Cromer to Menelik in consideration for article 3 of the 1902 treaty, together with a further provision increasing to £20,000 of the annuity to be paid to Ethiopia as soon as the works were actually started. Colonel Doughty Wylie, who was then in charge of the British Legation in Ethiopia, was informed of Kitchener’s views and attempted to negotiate a treaty with Lij Yasu, Emperor Menelik’s successor, along the lines proposed by Kitchener.

However, because of the First World War and internal political struggles in Ethiopia the matter remained in abeyance again from 1915 until March 1920. In 1920, at the request of the Sudan Colonial Government, Major Dodds, Wylie’s successor, obtained Ethiopian permission for Sudan to send two officials to reside at Lake Tsana in order to make surveys.

In spite of his success in obtaining permits for these officials (Black and Grabham) and for other staff who subsequently joined them, Major Dodds did not believe that it would be worth attempting negotiations with Ras Taffari, the Regent, of Ethiopia. Dodds believed Taffari’s position would not be strong enough to enable him to overcome the objections by the Empress Zawditu, who succeeded Lij Yasu, and the local chiefs. Dodds was, however, instructed to open negotiations at the earliest moment he thought feasible.

Accordingly, in November 1922, Major Dodds commenced negotiations because the British Empire Cotton Growing Corporation was pressing the British Government to conclude an agreement based on two installment payments. The first payment up to a limit of £50,000 on the signature of the lease, and the second up to a limit of £150,000 on the completion of the reservoir and of an annual rent up to a limit of £30,000, to date from the completion of the reservoir. In May 1923, the British Minister in Addis Ababa formally communicated a draft treaty, to the Ethiopian Government.

In November Ethiopia announced, that it would conduct an independent investigation into the Tsana scheme before it took any decision. The British broke off the negotiations, “which can be resumed later with better chances of success,” and informed the Abyssinian Government that Britain “would regulate their future conduct towards the Abyssinian Government in the light of the attitude which the latter have seen fit to adopt.” Nothing further transpired until Taffari’s visit to England during the summer of 1924 when the British Prime Minister (Mr. Ramsay MacDonald), explained Britain’s reasons for wishing to secure the concession.

On July 26th 1924 Ras Taffari, who was by then on his way back to Ethiopia, replied in a letter to the British Prime Minister as follows:

The Ethiopian Government in its own interest and for all other purposes is willing to build a dam in order to retain the waters of Lake Tsana … It is also willing to rent to the Sudan Government the surplus waters … For this work it will engage the services of a capable engineer … The Abyssinian Government will then compute the benefit that the Sudan Government will derive from the renting of the water … and fix the amount which shall be paid annually to it by the Sudan Government … After the engineer has finished the work … the Ethiopian Government and the Sudan Government will discuss the amount of money that will annually be paid to the Ethiopian Government for the waters … and any other question in connection therewith. After this an agreement will be signed and the work will begin …

On August 14, the British Prime Minister replied:

the course you suggest appears to offer a chance of an arrangement being reached which would be beneficial both to the Abyssinian Government and to the Sudan.

In March 1925 the whole question was reconsidered by the British, and it was decided, in the interests of the Lancashire cotton industry and of the economic future of the Sudan, that renewed efforts should be made in order to persuade Ethiopia to meet British wishes. It was decided as a first step to secure the support of the Italian Government based on proposals made by Italy in November 1919.

Britain also decided that an attempt should be made, in case of an Anglo-Italian Agreement being reached to secure the support, or at least the acquiescence of the French Government. The views of the Sudan Colonial Government were also obtained and found agreement with those of the British Government. On June 9, the British commenced the discussions, which resulted in the exchange of notes between Great Britain and Italy in 1925.

Following settlement of the crisis surrounding the December 25 exchange of notes, between Britain and Italy, the British Government renewed efforts to secure the acquiescence of the French. The British believed that French support for the British project would have to “be purchased.” On August 4 1926, the French announced that the Italian Government had been informed that instructions had been sent to the French Minister in Ethiopia to maintain friendly and sympathetic neutrality about Anglo-Italian desires in Abyssinia. France considered the British aspiration perfectly fair and unlikely in anyway to injure Abyssinia; in fact, they would probably be of direct benefit.

Accordingly, the British Government decided to renew the negotiations with the Ethiopian Government, taking as a starting-point the proposals of Taffari in 1924. It was felt that, until preliminary negotiations had taken place, it was premature to decide whether the concession should be asked for in the name of the British Government or the Sudan Government, or of a commercial concern with an Anglo-Abyssinian board of directors and capital.

Isolating Egypt

On August 28th 1926, Mr. Henderson, the British Acting High Commissioner at Cairo, called attention to the possible advantages of securing the goodwill, and even the active cooperation, of the Egyptian Government, pointing out that, as had been publicly stated, the dam would benefit Egypt as well as the Sudan. Mr. Henderson suggested that such cooperation would eliminate possible Egyptian encouragement to Ethiopia to oppose the scheme, might tend to lessen Ethiopian suspicions, and might result in Egyptian financial support being more readily forthcoming.

On the other hand, he pointed out that the Egyptian Government might possibly seize the opportunity to advance excessive demands as regard the disposal of the additional volume of water made available. Another possible objection was that the Egyptian Government might insist on participating in the negotiations.

The British decided that it was unwise to bring Egypt into the negotiations until success seemed assured. Further, it would be impossible to offer to Egypt a definite percentage of the water to be made available at first. Egypt might perhaps take a large percentage, but eventually the Sudan would require, and would expect to receive, the whole, or almost the whole, on the hypothesis that by then Egypt’s needs would be met by the dams at Gebel-Aulia and Lake Albert, plus the Sudd channel.

Mr. Henderson was also informed, however, that the British Government should have nothing to conceal. The text of the Anglo-Italian agreement had already been communicated to Egypt, who, if they raised the question, could be informed that negotiations were to be resumed with Ethiopia. Should Egypt touch upon the allocation of the water, they would be informed that a discussion on this point would be premature and would have to be decided in the light of the division of the Nile waters as a whole.

Mr. Bentinck on May 3 delivered a memorandum to Taffari, suggesting that the British Government should be granted the necessary permission to construct the dam and that such rights would not imply any encroachment upon Ethiopian sovereignty. At the same time, Mr. Bentinck handed to Taffari the draft of a treaty. On September 22, Taffari addressed a reply expressing surprise at the terms of the British proposals in view of the intentions of the Ethiopian Government as expressed in Taffari’s letter of July 26, 1924, to Mr. Ramsay MacDonald. Taffari reiterated that Ethiopians proposed to build the dam themselves.

On November 4, 1927, the United States press prematurely announced that Ethiopia had concluded a contract with J. G. White Engineering Company of New York [White] for the construction of the dam. But on the following day, the US State Department informed the British Government that, so far as the State Department was aware, no contract had been signed, or could be signed, as payment was to be effected by the issue of bonds, the principal security for which would be the rent paid for the water by the Sudan Government, whose agreement would first have to be obtained.

Under the proposal, waters of the lake were to be leased for thirty years to a corporation of bondholders and stockholders to be formed in New York with power to build a dam and sell the water. At the end of this period, the dam and the revenues would revert to Ethiopia. A clause was included providing for the generation of hydroelectric power. There was to be a road from Addis Ababa to the dam.

White, as the result of their study of the Grabham and Black Report and of their discussions with the Ethiopian Government, envisaged a US $20 million proposition. This sum was to be financed partly by a public bond issue and partly by stock held by their own finance corporation and other associated firms such as J. P. Morgan. The bonds were to carry eight percent interest; and an essential feature would be a guarantee by the British Government. The figures envisioned a rental in the neighborhood of £750,000 a year.

The publication in November 1927 of the announcement that Ethiopia was in negotiation for the construction of the dam caused a panic in the Egyptian press; which concluded that Egypt was threatened with imminent danger by what was “another diabolical move” on the part of Britain. According to the British, Egyptian interest in the question would not be ignored.

One of the main factors in the scheme was that the Tsana waters would be used by Egypt until such time as they were required by the Sudan, and it was hoped that for this reason the Egyptian Government would contribute substantially to the cost of the dam. The Egyptians felt reassured and withdrew their objections, and in February 1928 the British High Commissioner in Cairo authorized Mr. MacGregor, Irrigation Advisor to the Sudan, to place himself in touch with the Egyptian Minister of Public Works for unofficial discussion as to Egypt’s eventual cooperation.

On March 12 1928, Taffari explained that contacting an American firm was in concert with the wishes of the Ethiopian people who were afraid that the grant of the concession to a British company would eventually result in annexation of the country by Britain. Such fears had been increased by the Anglo-Italian agreement of 1925. On March 24, the British expressed the desire to negotiate on the basis of the Ethiopian Government arranging for the construction of the dam, provided that the British were satisfied as to the competence of the engineers.

Subordinating Ethiopian Interest

On May 16 1928, Ethiopia formally announced that they were negotiating with White and after concluding a suitable agreement, would show that agreement to the British Government. The British decided that before replying to the Ethiopian note it would be as well to try to reach some definite agreement with White. If the British could really satisfy themselves that White could be relied on to act loyally towards the British, the final negotiations might be left to the conduct of White’s representative in Ethiopia, particularly, as the British Minister would always be available to offer White’s representative advice.

Officially, as between the British Government and the Ethiopian Government negotiations could proceed between White and the Ethiopian Government to enter an agreement for operating the dam, providing Britain was satisfied, when the negotiations were concluded, that the agreement was a reasonable one. The British discussed their plan with White, and it was also suggested that MacGregor pay a “private” short visit to America, without the prior knowledge of the Ethiopian Government, to discuss the whole question of the dam. White agreed and the meeting was arranged.

Following his visit Mr. MacGregor reported:

[Dunn] regarded the Abyssinian Government as his clients for the time being, and therefore he could not very well show me the document.

… I went over the technical ground with him. In particular, we discussed the scope of the work at the lake, and the handling of the outfall problem. After this, I left Mr. Dunn and his associates to assimilate their fresh knowledge and to readjust their views on the whole undertaking.

Their primary reaction to the new facts was to scale down their conception of the cost to a figure of 6 million dollars to 8 million dollars. This, in the opinion of the financially interested parties, appeared to change the whole nature of the proposition. They thought that it was too small to be the subject of a satisfactory bond issue. Apart from this they had begun to realize some of the difficulties, e.g., the fact that the rental would necessarily be small in the early years of the under-taking, and would be payable by Egypt, not by the Sudan. They also realized that neither the British nor the Egyptian Governments could reasonably be expected to pay the high rate of interest demanded by American investors when they could finance the work out of their own resources, or borrow at say 5 per cent.

It was clear, also, that it was not sound finance to attempt to amortize the cost of a permanent asset like a dam in the early years after completion and before the works become fully productive. They became conscious, too, without my stressing the point that a body of foreign bondholders would fit uneasily, if at all, into the scheme of things on the Nile.

In the result the whole idea of a corporation of New York investors acquiring a lease of the lake with a view to sub-letting the water to the Sudan appeared to die a natural death as the situation was elucidated.

Arising out of this development, I asked Mr. Dunn whether, so far as he was concerned, the bondholder scheme was an essential feature, or would he be prepared to carry out the work for us in the general way of his business. He said that he would be very willing to do so, but he understood quite definitely … that Ras Taffari attached the greatest importance to the principle of American capital, and was determined that the undertaking should be entirely non-British. I said that we had not got that impression, and that, unless my memory was at fault, Ras Taffari had himself once suggested a mixed company containing both British and American capital. In any case, I said, Ras Taffari was not in a position to squeeze us into an unsatisfactory arrangement.

As regards tactics, Mr. Dunn proposed to continue to press … to secure Ras Taffari’s agreement to the draft concession. This was the natural course for him to take as he had been offered an attractive piece of business, and as he was not supposed to have any communication with us there was no reason for him to depart from the basis of his negotiations with Taffari. It could not commit us in any way. When he had secured the concession he must naturally approach us to discuss terms.

It would at once become apparent that we could not possibly pay a rental sufficient to meet their scheme of finance and it would be necessary to seek means, of reducing the engineering and other costs. I said that this seemed to me a perfectly sound view of the position. I added that Ras Taffari, having committed himself to a scheme, which turned out to be unworkable, would find it difficult to oppose the recasting of the scheme on workable lines.

I had suggested to Mr. Dunn that he should arrange to send out an engineer to reconnoitre the ground so as to get a closer approximation of the cost of the works. Mr. Dunn, however, thought it would be better to postpone that until he had clinched his deal with Ras Taffari. After further consideration I came to the conclusion that Mr. Dunn’s line was the sounder one, and that the adjustment to realities should take place after the Ras had granted the Dunn concession. The terms of this on the financial side are so wildly impossible that no one would be committed except Ras Taffari. It was understood that Mr. Dunn would continue to try to get his concession through.

At my last interview with Mr. Dunn he said that he was very keen to get the job of building the dam. He repeated his assurances of good faith and his anxiety to help us in every way and to give us “a square deal.” He went so far as to say that he was not selfish in the matter, and that if at any stage of the proceedings we would prefer him to fade out of the picture he would be prepared to do so. He thought, however, that having regard to Ras Taffari’s attitude, we ourselves would gain by employing an American agency.

I said that I had the fullest confidence in his good intentions and in the ability of his firm to carry out the job if it came into their hands. I thought that his views as to the value of American support was sound. We had never objected in principle to the employment of a foreign agency; we had only insisted that the agency should be such as to command our confidence. I mentioned the case of M. Zorg, the Swiss engineer, who, we believed, had made some report to the Ras regarding the dam, though nothing further had resulted, and we had never been able to get a copy of the report. I thought the Ras was perhaps inclined to use this question of a foreign agency as a means of procrastination.

On receipt of MacGregor’s report of his discussions in America, the British Government decided to raise no objection to direct negotiations proceeding between Ethiopia and White. This decision was conveyed to Taffari (now King Regent of Ethiopia) in a note of December 19 1928. White sent a representative to discuss matters with the Ethiopian Government, and was successful in obtaining an undertaking from Taffari that they would be given the contract. Taffari also proposed a conference between representatives of the British, Ethiopia, and White to reach an agreement on water requirements, after which negotiations could be commenced to settle the terms of the construction contract.

Subsequently, Taffari informed the British that, before he could proceed further, information was required as to how much water Sudan would require and how much they would pay. It was arranged that a conference should be held at Addis Ababa, which would be attended by British experts. As preliminary to this, meetings were to be held in London in the autumn of 1929 between representatives of the British, Sudan and White in order to discuss the financial and technical aspects of the project.

Anglo-Egyptian Exchange of Notes of 1929

Towards the end of 1928 the British realized that collaboration with Egypt might be necessary to secure Egyptian financial backing. However, the British decided to delay the collaboration to leverage the acceptance of the 1925 Nile Commission’s report by Egypt (then under discussion). When the negotiations were concluded by an exchange of notes signed in May 1929, the British immediately informed the Egyptian Government of the status of the Tsana negotiations. The Egyptian Prime Minister immediately questioned why a conference was taking placing regarding the Nile at which the Sudan but not Egypt was represented.

At the end of December, notes were exchanged between Egypt and Sudan allowing the British Government to represent the interests of Egypt and Sudan during the preliminary phase of the negotiations to secure the Ethiopian Government’s consent to the principle of the construction of the reservoir.

The British agreed to keep Egypt fully informed and gave the assurance that no agreements would be entered in regard to the plans, storage, allocation, cost or the rent which might eventually be necessary to pay to Ethiopia, without prior consultation with the Egyptian Government.

The conference at Addis Ababa between the Ethiopian Government, British experts, and White opened in January 1930. As was “agreed” in the secret meeting in New York between White and MacGregor, the initial proposal made to the Ethiopian Government by White was demonstrated to be financially prohibitive. The British therefore proposed that White further ascertain the exact cost of construction and operation of the dam and the cost of construction of a road linking Addis Ababa to the lake, the latter having been put forward by Ethiopia as an essential condition of the agreement.

The purpose of the meeting was to scale down the project as agreed, in the meeting in New York, between White and MacGregor. It was also agreed that Sudan should meet the cost of these additional surveys by paying the sum of £E 16,000, to the White Company. This arrangement was confirmed in an Exchange of Notes of March 4, 1930.

In February 1930, in accordance with the Anglo-Egyptian Exchange of Notes of December 1929, Egypt was informed of the position reached at Addis Ababa. In April Egypt was also informed of the arrangement that had been reached with Ethiopia for further surveys at the expense of the Sudan.

The Emperor finally presented Sir S. Barton, the new British Minister in Addis Ababa, a copy of a draft containing an outline of what the Emperor had in mind in reference to an accord on Lake Tsana waters. Subsequently, in recognition of the joint benefits to be derived, the Emperor proposed an amendment to Article 7 of his draft be replaced by the following:

Seeing that the dam at Lake Tsana will constitute a system of irrigation for the two countries, the engineers of the two Governments will regulate the flow of waters to the needs of the countries.

By 1931, Ethiopia was in financial difficulties and Sudan was reconsidering its attitude towards the project because of unfavorable developments in the world cotton market. On the other hand, the British believed that it was necessary to come to a decision when the engineers sent out by White submitted their report and estimates to achieve the result sought for the last thirty years.

The British suggested that, if Sudan, for financial or other reason, was unable to reach an agreement with the Ethiopian Government, Egypt might be willing, in partnership with Sudan, to finance an option or the possible construction of the reservoir. In such a partnership, Egypt would assume a larger part of the financial burden, under which the Sudan might retain the right to increase her share at any time in the future up to fifty percent.

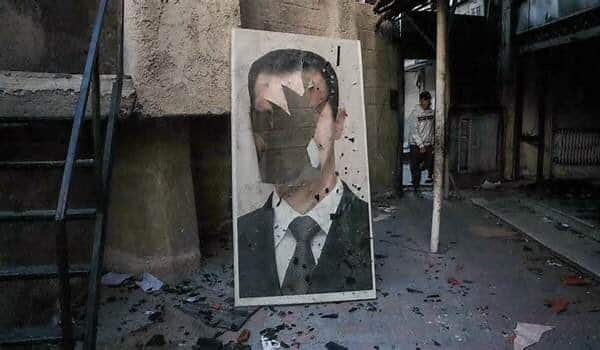

Part 2 of the article will discuss Egyptian and British complicity in the invasion of Ethiopia by fascist Italy.