How Addis Ababa deals with ethnic violence in the region of Benishangul-Gumuz will determine the country’s future.

On Dec. 22, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed visited the vast lowland territory of Metekel in Ethiopia’s far western region of Benishangul-Gumuz, the so-called homeland of five indigenous ethnic groups of which the most populous are the Berta and the Gumuz. It was his first known visit to Metekel, a strategically important area that includes the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) and which has been afflicted by an endless string of gruesome, ethnically targeted massacres in recent months. “The desire by enemies to divide Ethiopia along ethnic & religious lines still exists,” Abiy tweeted following a meeting with local residents and officials. “This desire will remain unfulfilled.”

The next day, more than 200 people—ethnic Amharas, Oromos, and Shinasha—in the village of Bekoji were slaughtered by heavily armed men from the local Gumuz ethnic group in a devastating raid that began at dawn. “No value added,” an angry resident of Assosa, the regional capital, told me over the phone after Abiy’s visit. “He came for nothing.”

The trip to Metekel came a little less than a month after Abiy declared victory in the northern region of Tigray, where Ethiopia’s armed forces have been battling the country’s erstwhile ruling party, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), which dominated Ethiopian politics for decades before it was sidelined by Abiy. Yet that war is not over: Fighting persists in several places, and more than 50,000 people have so far fled to Sudan. The TPLF, whose leadership withdrew to the mountains on Nov. 28, continues assaults against a coalition of Ethiopian federal troops, militiamen from the neighboring Amhara region, as well as an unconfirmed number of soldiers from Eritrea to the north.

While the Tigray war rumbles on, violence elsewhere is spreading to an extent the central government cannot ignore.

But the visit to Metekel was a sign that while the Tigray war rumbles on, violence elsewhere is spreading to an extent the central government cannot ignore. Numerous civilians in Wollega, the far west of Oromia, Abiy’s home region, were killed last month, amid fighting between government forces and Oromo insurgents (who have also suffered hundreds of casualties in recent weeks). The government blamed the rebels for carrying out a massacre of at least 19 civilians. As in Metekel, many of these victims were ethnic Amhara living as minorities in the region.

In both territories, the army has been deployed to restore order: The government of Benishangul-Gumuz called for federal assistance four months ago, following a series of killings that began on Sept. 6. (Federal troops were first sent to Wollega in early 2019.) Prefiguring an approach that would soon be taken on a much larger scale in Tigray, security operations reportedly have also involved Amhara regional security forces, which crossed over the border into Metekel.

The deployment of such regional forces—well armed and ethnically exclusive—is a troubling feature of recent conflicts throughout Ethiopia, but Abiy’s extensive reliance on Amhara troops in Tigray, and to a still limited extent in Benishangul-Gumuz, highlights their growing importance to his security strategy, a development viewed with skepticism by some, including those in his own Oromo camp, who resent their ascendancy.

The fighting in Benishangul-Gumuz has since fragmented, with elements of the local regional security apparatus siding with Gumuz militiamen against the federal army and the line between Gumuz combatants and civilians blurring. “The response of the federal army is to take action on all Gumuz because they can’t identify terrorists from civilians,” a driver working for the regional government forces in Metekel told me.

The bloodshed is also increasingly grisly. Witnesses in Metekel report summary executions, the slaughtering of babies, and the disemboweling of corpses by Gumuz militias. Calls for stronger military measures, particularly from Amhara, are growing louder. In early December, Amhara’s chief of police said he had requested permission from the federal government to intervene in Benishangul-Gumuz. A few days later, a spokesperson for the Amhara regional government warned that if massacres continued, then the state would begin a “second chapter” of the war in Tigray—this time in Benishangul-Gumuz. In October, the country’s deputy prime minister, who is ethnic Amhara, called for Amharas in Benishangul-Gumuz to arm themselves. On Dec. 24, Abiy said he was sending even more troops to the region.

Formally incorporated into the Ethiopian Empire in the late 19th century, Benishangul-Gumuz has long been a frontier space between more powerful neighbors: the Sudanese to the west, highland Ethiopians to the northeast, Oromos to the south. Its indigenous populations—of which the Gumuz, Berta, and Shinasha ethnic groups are the largest—were prey to slave-raiding from all three for centuries and treated as racial inferiors for many years after.

Under Ethiopia’s 1995 constitution, which was largely devised by the TPLF, Benishangul-Gumuz was granted a degree of formal autonomy, with leaders drawn from the local elites. The Benishangul-Gumuz constitution, revised in 2002, designated five ethnic groups as “owners” but excluded the many Amharas, Oromos, Tigrayans, and Agaws who are deemed residents, not citizens.

The Benishangul-Gumuz constitution, revised in 2002, designated five ethnic groups as “owners” but excluded the many Amharas, Oromos, Tigrayans, and Agaws who are deemed residents, not citizens.

They are permitted to vote but cannot, in effect, run for elected office—though they are represented to varying degrees in the local bureaucracy. This makes explicit what is only implicit in the federal constitution: a division between “natives” and “outsiders” whose formal rights, in particular to land, are unequal.

Some of these so-called outsiders were settled in the region in the 1980s, as part of the then-military government’s response to the droughts and famines of that decade. But recently their ranks have swelled, with migrants from the densely populated highlands looking for untouched land or work on commercial plantations; Benishangul-Gumuz is one of the few places in Ethiopia where it is still possible to acquire sizable tracts.

In Metekel, this typically meant Gumuz being pushed out by Amharas and Agaws, many of whom were later evicted in turn; in Kamashi, in southern Benishangul-Gumuz, the pressure came from the Oromos of Wollega. The construction of the GERD in Metekel, close to the border with Sudan, has created new jobs and resources that largely benefit non-Gumuz groups; at the same time, though, it has accelerated the scramble for preeminence in the region.

Seen from a longer view, low-intensity violence is less the exception than the norm. Benishangul-Gumuz was also plagued by rebellion and communal conflict in the early 1990s, an era that shares similarities with the messy shift that began in 2018.

Typically, violence was between so-called settlers (known locally as qey, or “light-skinned”) and the indigenous groups, but it also occurred among the so-called outsiders—Oromos, Amharas, Tigrayans, Agaws—too: The brief occupation of Assosa in 1988 by the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) resulted in a massacre of around 300 Amhara peasants. In 2018, after the OLF returned from exile at Abiy’s invitation, there was a renewed bout of violence between the Oromos and Gumuz over land and resources in Kamashi, which includes rich gold deposits. Scores of people died, and some 150,000 were driven from their homes.

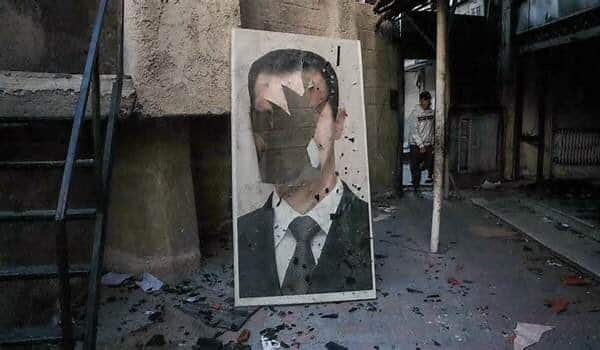

But now the violence is a matter of national importance and not only because of its exceptional scale and intensity. It is also an essential part of the arsenal of allegations deployed by the federal government to justify military intervention in Tigray. This was spelled out in a Nov. 12 statement from the prime minister’s office, which claimed that the “hidden hands of the TPLF” were behind killings of civilians in all corners of the country as part of a plot to destabilize the new administration.

A TV documentary produced by the federal police and broadcast on state-owned channels four days earlier was more specific. It claimed that individuals including a Tigrayan businessman in Metekel had been paid by one of the TPLF’s founders, Abay Tsehaye, to organize Gumuz militias and attack Amhara civilians in the region. At other times, the federal government has claimed that the violence has been orchestrated to interrupt the construction of the GERD, a source of tension between Ethiopia and downstream Egypt that Abiy believes the TPLF has tried to exacerbate.

Such notions are also pervasive within the region itself. “The TPLF are the ones disturbing everything, everywhere,” a resident of Assosa told me in October. As in other peripheral parts of Ethiopia, including neighboring Gambella, the relative underdevelopment of Benishangul-Gumuz has long accorded outsiders disproportionate economic power and influence.

The TPLF’s dominance of the previous ruling coalition, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, and its related patronage networks before 2018 meant Tigrayans were particularly prominent. They owned some of the largest agricultural investments, especially in Metekel, while TPLF-owned or affiliated businesses enjoyed a substantial share of subsidiary contracts in, for instance, the construction sector (as they commonly did elsewhere in Ethiopia).

The fact that the region’s president, Ashadli Hasen, a Berta, was appointed in 2016 and has not been replaced gives an illusion of continuity. But in reality TPLF influence in the region has waned since 2018. Several Tigrayan investors have had their licenses revoked for failing to develop their agricultural leases (a pattern seen elsewhere in the country), while others—reportedly including a wealthy hotel owner in Assosa, according to local sources—have been arrested. Tigrayans are also less prominent in the local bureaucracy than they once were. All this suggests that the carnage in Metekel may be less the result of deliberate sabotage by the TPLF than of a chaotic rush to fill the vacuum that it left behind.

There is, however, little doubt that Amhara civilians have borne the brunt of the bloodshed. Gumuz militias have reportedly told their victims that they would be killed for not respecting orders to leave their region.

“In terms of population, the Amhara are the second most populous in Benishangul-Gumuz. In terms of influence, the Amhara are the most influential, especially in the towns. In terms of the economy, they play a leading role. All these factors contributed to the killings. Why? Because the indigenous populations think the resources are controlled by ‘others,’” a senior Amhara official told me in November.

But it is also clear that violence has gone the other way, too. In 2019, some 200 Gumuz (and Shinasha) were allegedly killed by Amhara militias following tit-for-tat clashes on the Amhara side of the disputed border between the regions, which locals in Benishangul-Gumuz complain went unreported and unpunished. “The government kept silent. They didn’t take action against those who committed that crime,” said Zegeye Belew, a student in Assosa. “Nobody speaks about that genocide.”

During Abiy’s visit, a Gumuz participant in the meeting alleged that Amhara militias and youth groups were “blindly invading” the region in order to grab the land. “They want to chase us away. They’re saying the Gumuz are Sudanese,” he said. “The people of Gumuz were belittled in the past. But now we’re told that we should be exterminated.”