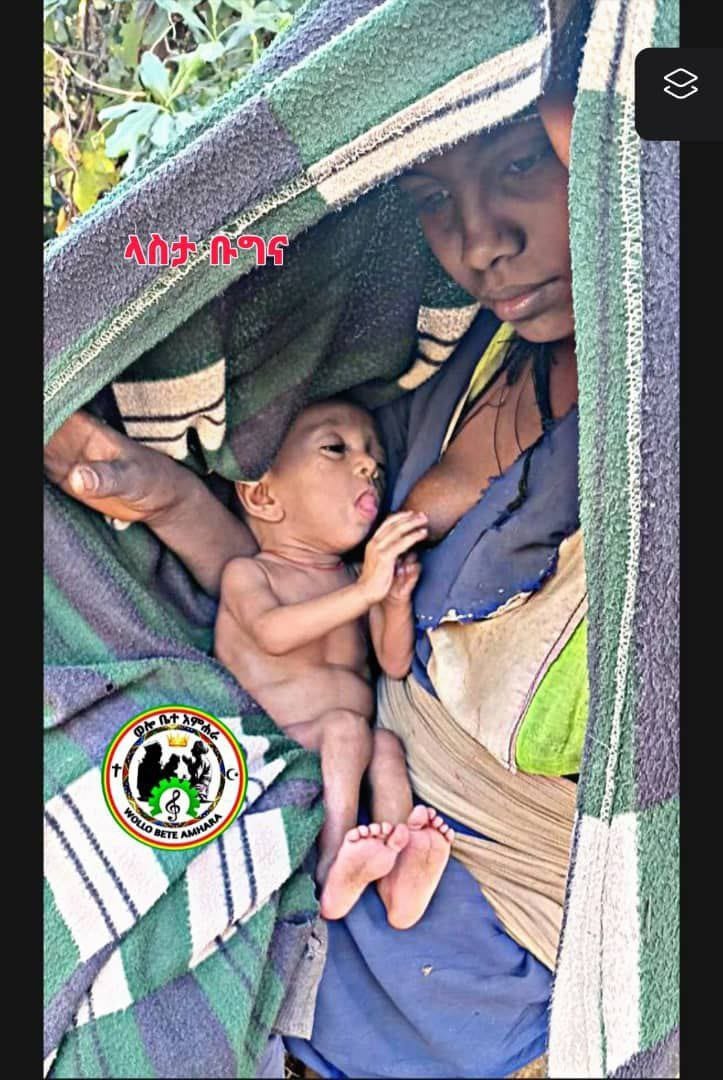

The dark cloud of national-suicide is hovering over Ethiopia. Ethnic killings, extreme poverty, endemic corruption, soaring inequalities, attacks on religious freedom, assaults on personal liberties, the lawlessness of the security forces, and the Zära Yacob syndrome that seems to have taken over the Prime Minister are shrinking the space of freedom, equality, justice and peace. Ethiopians are caught between hope and despair: hope that they will overcome the present obstacles and give themselves a country where every person could live freely and peacefully; despair that the present situation could deteriorate even further, landing them in a catastrophe that will make life unbearable for all. Which will triumph: hope or despair?

Answering this question requires stepping back from events and extemporary reactions, and reflecting carefully on Ethiopia’s problems, what kind of Ethiopia we want, and how to get there, all in ways that will get the assent of Ethiopians. The present text suggests one small step in this direction.

Let us assume that Ethiopia’s future could be that of a prosperous, free, just, and intellectually vibrant society in which all Ethiopians will unconditionally have the right to accede to all the resources necessary for a life that enhances their cognitive, material, spiritual and physical well-being. This means transforming Ethiopia into the “good society.”

One may object that contemporary Ethiopia is a society that suffers from deep political, economic, and social pathologies: to expect that such a society could be transformed into the “good society” is utopian. This objection is credible, but only from the perspective of technocrats and bureaucrats whose expertise and imagination are wedded to Western visions, interests and knowledge. We should reject this objection. If Ethiopia finds herself in the present dire situation, it is because Ethiopians lack a utopian vision: one that is driven by a historically “educated hope” that discloses the tendencies and latencies of emancipation that gestate in Ethiopian history both “vertically” and “laterally” (trans-ethnically). Such a utopia is a “realistic utopia.”

Many philosophers and social scientists have pointed out the important contribution of utopian thinking for creating a better society. Utopian possibilities have always first gestated in thought before they are translated into reality. It is this historical transformation of utopian visions into reality that led Goethe to claim, “only humankind can do the impossible possible.” Karl Mannheim notes, “We cannot imagine… a society without Utopia, because this would be a society without goals. With the relinquishment of Utopias, man would lose his will to shape history and therewith his ability to understand it.” This is a point made by many thinkers, including the neglected Ethiopian thinkers of the qiné and Islamic (Wallo) traditions.

Utopian visions are present in Ethiopia’s intellectual traditions since at least the 13th century, though we have neglected them due to our Gibbonist education. The utopian vision of creating the “good society” is powerfully expressed in the works of Lalibela (13th century). He enjoined Ethiopians to build the “heavenly Jerusalem here on earth,” the “good society,” as it were. He encouraged them to “speak up” to power, to live as “equals,” to master the knowledge of the “bowels of the earth” (what we would call today science and technology), and told them to “hurry up” to create the “good society.” The vision of the “good society” was also present in the teachings of the Däqiqä Estifanos (15th century) who told their followers that one must always aspire to “reach the summit” of what one could be. The 19th century Islamic revival in Wallo entertained the ideas of the “good society.” Even presently, the utopian vision expresses itself in Awra Amba (in Fogera woreda, South Gondar).

We find similar utopian visions in the original gada system. The original gada gestated the utopian ideas of the “commons” and of “commoning.” Its practice of moggaasa transcended ethnicity and pointed towards universality. It considered the provision of “protection and material benefit” to “weak Oromo or non-Oromo” a universal social responsibility. The original gada incubated the “8 generation rule.” It enjoined people to examine their ways every 8-generation to resolve the new challenges generated by the passage of time. The “8 generation rule” intimates the realistic utopian vision that the future is in our hands.

Utopian thinking opens an “extraterritorial space” that allows us to cast an “exterior glance” on our reality, exposing it as unacceptable. It thus enables us to look beyond the present and see alternative ways of thinking, acting and living that we cannot see now, because our political and intellectual horizons are gravely limited by our refusal to leave our ethnic wombs. One of the great tragedies of contemporary Ethiopia, brought about by Gibbonist education and our incapacity to shed our ethnic placenta, is the erasure of the universal utopian dimension of gada culture and its debasement into a source of a violent ethnic ideology. Yet, the universalist dimension of gada tells us: Marii’ atan malee maraatan biyya hinbulchan.

We need to critically appropriate the universal utopian dimensions that simmer in our history—vertically and horizontally—and judiciously re-work them in order to expand our historical imagination in our reflections on our present multiple questions, needs and concerns. It is the lack of such realistic and critical utopian thinking in contemporary Ethiopia that Bäewqätu Siyum, the Ethiopian poet, laments in his ስብስብ ግጥሞች (134):

ሜዳ አድርግት ዳገቱን / Others have flattened the escarpments

ወዴት ላድርገው ጉልበቴን / How could I test my strength?

ከሁሉ በላይ ሽንፈት / I am filled with pride

ያልተዘጋ በር መክፈት / Though I open the doors others have opened

ባክህ ላክልኝ ፈተና / Please put me to the test

አቅሜን ይነግረኛልና/ So that I would know my powers.

The poem intimates that though we Ethiopians are “filled with pride” we nevertheless shun “testing” ourselves by letting others (Westerners, etc.) conquer our “escarpments,” open our “closed doors,” conceptualize our problems, and theorize on our conditions. The West calls “development aid” what it does in our place. It tells us the knowledge of our conditions that it produces is “scientific” and that we have to accept it. We believe these claims and become eager recipients of the knowledge welfare it bestows on us.

However, as Negadras Baykedagn, the early 20th century Ethiopian thinker put it, Ethiopia will decline if Ethiopians abide by knowledge welfare, which he called “broken words,” (in ሥራዎች, 104). Knowledge welfare imprisons us in “broken words” that render Ethiopia “a society without goals”; it subverts our will to go beyond the confines of our ethnic particularities and prevents us from working as a people to make Ethiopia the “good society.”

A century of knowledge welfare has not enabled us resolve Ethiopia’s problems. On the contrary, knowledge welfare has become the crucible of the ethnicization of Ethiopian history and alienated us from each other. It has made us opaque to ourselves and transformed Ethiopia into a political, economic, and intellectual wasteland. That’s why the poem rejects knowledge welfare and pleads: “Please put me to the test / So that I would know my powers.” Having abandoned our birthright to be the authors of our own emancipation as a people, the catastrophe of national-suicide is now hanging over us. How could we avoid this catastrophe-to-come? I will conduct a zäräfa of catastrophe theory to suggest one realistic answer.

The relation between catastrophe and the “good society” is a säm ena wärq relation. This means that the two are not mutually exclusive. On the contrary, it is by working-through the catastrophe-to-come as säm that we could generate the ideas of the “good society” or wärq Ethiopians could create. To see this, let us project ourselves into the future—the Ethiopian catastrophe-to-come—and live it as the fate that awaits us.

Here is the Ethiopian catastrophe-to-come into which we have to insert ourselves imaginatively: Ethiopia will no longer exit. Her territory will be carved up into ethnic states run by ethnic dictators. Like the multi-celled cnidarians that engaged in regressive evolution and evolved backward to become single-celled myxozons, Ethiopia will historically regress and evolve backward into single-celled ethnic states. All her cultural achievements, including the 2,000 years old Orthodox Church and the equally old Ethiopian Islam, will disintegrate into rituals of ethnic politics. Thousands of Ethiopians who reject ethnic dictatorships will become refugees scattered in Africa, Europe, America and beyond. Since the new ethnic states will have little political, economic, and intellectual weight, they will be puppets of the powerful states of Europe, America, Asia, and Africa. Such will be the death of Ethiopia: the catastrophe-to-come.

We Ethiopians should stage now the mourning of the coming death of Ethiopia that, though it has not yet occurred, will surely occur if the present calamitous conditions persist.

Mourning the death of Ethiopia means situating ourselves in this future catastrophe and retroactively inserting counterfactual political, social, economic measures into the past of this future (which is the present in which we now live). That is, we reflect: if we were to do “this” and “that,” now, we could change the direction of our present history away from the catastrophe-to-come. In the process, we figure out alternative political, social, economic paths that could lead us to the “good society.” As Awra Amba shows us, figuring out the counterfactuals that could lead Ethiopia to a better future is the duty of all Ethiopians who want to make Ethiopia the “good society.” It is a collaborative and inclusive future-oriented task.

The catastrophe-to-come approach thus suggests that utopian thinking contributes to the identification of the social, political and economic paths that aid us to prevent the coming catastrophe and to build the “good society.” Were we to recognize and confront now the approaching death of Ethiopia and develop alternatives that prevent it, we would have laid the ground for transforming Ethiopia into the “good society.” We would have then, as the Däqiqä Estifanos would say, “reached the summit” of what we are capable: free, equal, peaceful, and just human beings.

Hope would have then won over despair.

Maimire Mennasemay, Ph.D. Scholar in Residence, Humanities/Philosophy Department, Dawson College, Montreal, Canada. mmennasemay@dawsoncollege.qc.ca