Your Excellency:

Your Excellency:

I am a US citizen who has advised Ethiopia’s anti-TPLF opposition on an unpaid basis since 1991 and am probably the TPLF’s most outspoken foreign critic. My partisan perspective on the Tigray conflict is surely distinct from a career diplomat’s such as yours. Yet I take the liberty of sharing this feedback on your Nov. 2 speech at the United States Institute of Peace, inasmuch as it reflected US, AU, and, more generally, western policy, in the hope you will consider my different point of view.

Your remarks expressed dismay at Ethiopians erroneously holding your Meles eulogy against you, frustration at the GoE’s refusal to heed the West’s call for a ceasefire, and, especially, admirable concern over humanitarian access and war crimes. You deny any American bias in favor of the TPLF.

I laud your goals but, based on my thirty years of experience in this field, fear their underlying strategy is proving counterproductive because it is based on several interrelated misapprehensions.

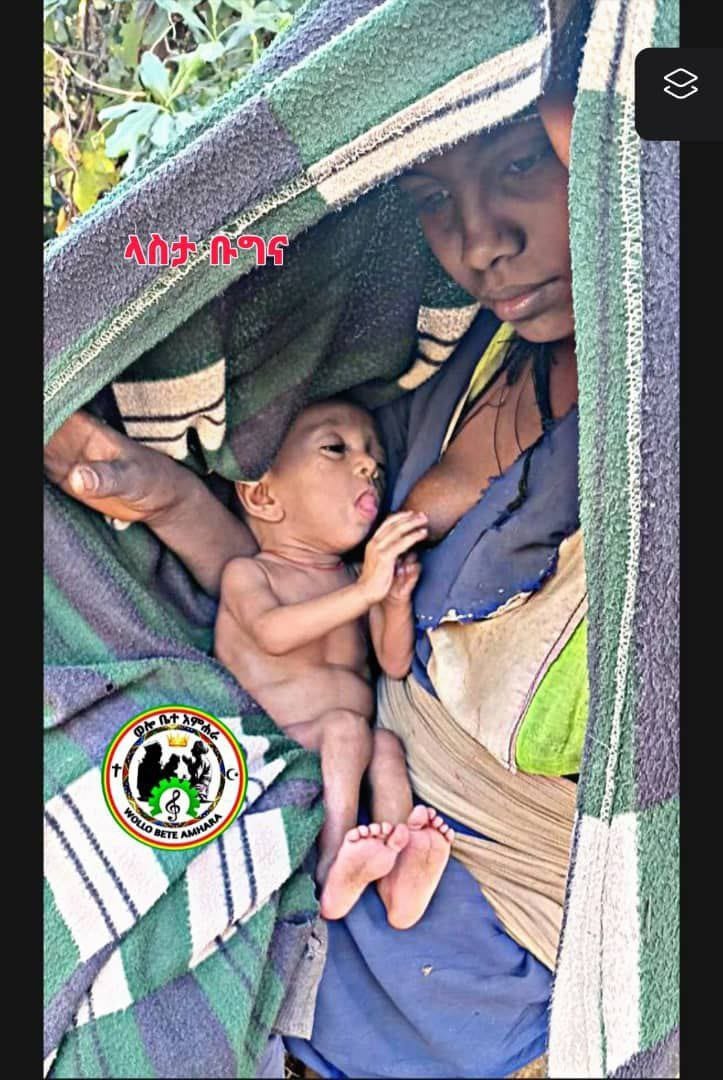

The first is a failure to properly appreciate the terroristic character of the TPLF. Already on the Global Terrorism Database, the TPLF has for decades unquestionably committed acts that only semantics or legalistic hairsplitting could relabel as something other than terror. They were certainly terrifying to their countless Ethiopian victims. Mere American acknowledgement of past TPLF “human rights violations” sounds perfunctory to them.

Unless one allows for the TPLF’s terrorist character, it will be hard to understand the degree to which Ethiopians take offense at calls for talks with that group and still begrudge your praise of Meles. Imagine some diplomat who had once given a speech extolling Bin Laden sought to advise Washington on the conflict between America and Al Qaeda. Would you trust that advice? For that matter, how would America respond to an ally calling for a ceasefire and talks between the United States and Al Qaeda? That’s what western and UN prescriptions sound like to most Ethiopians.

Another characteristic of the TPLF that American diplomats don’t seem to grasp is its intent to regain control of Ethiopia through a TPLF-controlled “transitional government” or “coalition” in order to resume its place at the national-level corruption trough. As you must know, the TPLF pursued that strategy while it was in power and afterward by exacerbating tribal tensions in a divide-and-conquer scheme. This national destabilization operation, linked to the other tribal tensions to which you referred and covertly supported by Egypt, will persist until the TPLF is decisively defeated or decapitated. Talks are unlikely to resolve anything because the TPLF’s history shows that its senior leaders see negotiations—facilitated by what they deem “useful idiots”—as stepping stones to domination instead of a means of finding a just and sustainable modus vivendi with the rest of the country.

Unless some mechanism can be proposed that renders the TPLF destabilization campaign physically impossible, peace talks, which would preserve such dangerous TPLF capability, will continue to be seen as a threat to “Ethiopia’s unity, territorial integrity, and stability” instead of a path to them. The conspicuous sidestepping by foreign diplomats of this reality in their calls for a ceasefire reinforces Ethiopians’ perception of American, European, and UN bias in favor of the TPLF.

Blaming the TPLF’s expansion of the war on the government cutting off humanitarian relief and access in Tigray instead of seeing that expansion as an opportunistic manifestation of the TPLF’s pre-existing plans for re-conquest of the country also sounds to Ethiopians like an inexplicable failure to accept what the conflict is really about. Since the TPLF’s intentions should be obvious to anyone who knows modern Ethiopian history, it is easy for Ethiopians to see pro-TPLF bias as the only possible explanation.

Mistrust and bitterness lead Ethiopians to find dark significance in western diplomats’ word choices. The term “western Tigray” sounds to many like the adoption of a TPLF-authored interpretation of history and approval of an illegal annexation by a criminal regime at gunpoint. US rhetoric frames discussion of Ethiopian international crimes as if they began with the fighting in 2020. This failure to give adequate weight to the longer history of TPLF atrocities, including genocide, and to recognize that the TPLF’s ostensible, regionally “stabilizing” former role was just the opposite, also make Ethiopians see America as strangely blind to the real issues at stake.

Even your implication that Ethiopian human rights are “parochial” matters in contrast to “lofty” UN principles is likely to dismay many. Ethiopians found nothing lofty about your or Sec. Guterres’ normalization of an unelected, homicidal kleptocracy when it was killing and torturing them. To Ethiopians, such language indicated either gross insensitivity or a craven abandonment of democratic values, either of which forever rendered the source unreliable.

Western diplomats and policymakers also don’t seem to realize the extent to which Ethiopians blame them for today’s state of affairs. As most Ethiopians see it, after helping make the Frankenstein monster at their gates, now the West wants them to treat it as a partner for peace and give it a chance to continue tearing their country apart and murdering them.

This attitude is rooted in Ethiopians’ painful memories of how the West, especially the United States, propped the TPLF up for decades with security and financial aid, diplomatic and moral support, and by refusing to react in a meaningful way to its crimes against humanity. They ask, where were the West’s moral outrage and sanctions during the twenty-seven years that the TPLF inflicted its ethnic-based violence on us?

Ethiopians remember Susan Rice’s grotesquely complimentary eulogy of Meles and her laughter over the 2015 TPLF’s 100% election “victory.” They remember President Obama’s cynical descriptions of the TPLF dictatorship as democratic. They remember American diplomats urging them to swallow the stolen 2005 election. The recent endorsement of Tedros Adhanom for director-general of the WHO is seen as another example of US indifference to Ethiopian lives.

No amount of humanitarian aid will wash away these stains on America’s reputation in Ethiopia. But I have never heard a single State Department representative convey the slightest regret for them.

I agree that the US does not want to see the TPLF re-take Addis. But Washington does appear to seek strategic balance between the warring parties. If so, that choice underestimates the existential danger to Ethiopia that the TPLF’s simple survival under its current leadership represents. It ascribes moral equivalency to a quasi-democracy and authoritarian forces. It legitimizes and discounts the TPLF’s prior history and unceasing aggression. And it belies your claim to understand that Ethiopia can’t tolerate an insurgency. These factors undermine Ethiopians’ confidence in what they already regard as a perfidious American ally.

Even the very evidence you offer of US impartiality, that the United States “consistently condemned the TPLF’s expansion of the war outside of Tigray and continue[s] to call on the TPLF to withdraw from Afar and Amhara,” deepens Ethiopian distrust by suggesting that a reversion to the prewar status quo ante would be a viable stage on the road to peace. No explanation is presented as to why Ethiopians should not view such a development as merely postponing the need to confront and end the TPLF’s destabilization efforts. Most fear that the ceasefire urged upon them by their duplicitous or, at best, naïve, American partner, already tainted by decades of collusion with the TPLF, will only facilitate the terror group’s resumption of its deadly subversion.

Failing to address squarely such popular anxieties and resentments hampers your ability to achieve America’s goals in this conflict. Even worse, these policy lapses and linguistic signals have fueled the conflict by encouraging the TPLF. America’s continued insistence on a ceasefire under these conditions wastes time, gives aid and comfort to the TPLF insurgency, mitigates against US foreign policy objectives, and creates regional opportunities for US adversaries.

In light of the foregoing, I urge you to give thought to a new policy that takes these facts into account and better aligns western and Ethiopian interests. First, and with all due deference to your illustrious credentials, contemplate stepping down as Special Envoy and allowing another diplomat without your baggage to take your place.

Second, the US should repair its credibility by acknowledging and apologizing to the Ethiopian people for its former complicity with the TPLF.

Most importantly, try the carrot instead of the stick. America should abandon its apparent goal of promoting a strategic GoE-TPLF balance which prolongs the combat by emboldening the insurgency. Offer instead to side resolutely with Addis Ababa and provide it with all the military, diplomatic, financial, and moral support it needs to put down the counterrevolution (except, of course, boots on the ground)—but only in return for greater, measurable Ethiopian cooperation on humanitarian access, human rights enforcement, GERD negotiations, new parliamentary elections in areas where intimidation by Prosperity Party supporters likely skewed the results, and the freeing of opposition leaders like Eskinder Nega whose charges are clearly unsupported by evidence.

Such a transactional policy shift will not sanitize or immediately end this nightmarish war, but that’s not going to happen anyway. At least, rationalizing conflicting American and Ethiopian aims in this manner will reduce the harm to Ethiopia’s people as much as realistically possible. It will foster regional stability by hindering TPLF destabilization plans and show the US finally takes that menace seriously. It will demonstrate to Ethiopia’s militant opposition that violence doesn’t pay. It will de-incentivize Egypt’s unhelpful behind-the-scenes role and lower overarching GERD tensions which endanger African security even more than the present crisis.

America’s policy is reminiscent of European colonialists of earlier times who thought they could make Africans understand them by shouting louder. It’s time to listen to Ethiopia’s people instead and inject more creativity and agility into the diplomatic process. Smarter policy can still help turn this war into an opportunity for long-term peace.

Sincerely,

David Steinman

Nov. 8, 2021

Does it really matter? USA’s policy is to keep the peace between Israel and Egypt alive at whatever cost. Egypt felt that the balance of power with regard to the Nile is slipping away from its hand if the GERD dam is completed. That upset a lot of Egyptians and they “requested” their government “What do we get as payment for peace with Isreal?” and that request ended up in Isreal and US political leadership and they, in turn, decided to destroy the central government in Ethiopia by supporting TPLF et al. It is the question of self-reliance and knowing your enemy. Antony Blinken and Jeffrey D. Feltman ( to mention some) are part of that puzzle. But something they have not asked themselves (US and the supports of this political premises) is will it solve their problem? For me, no. And there are million and one things that be done to counter their actions. Not a letter. But you have to do what you have to do. So I salute you.