By

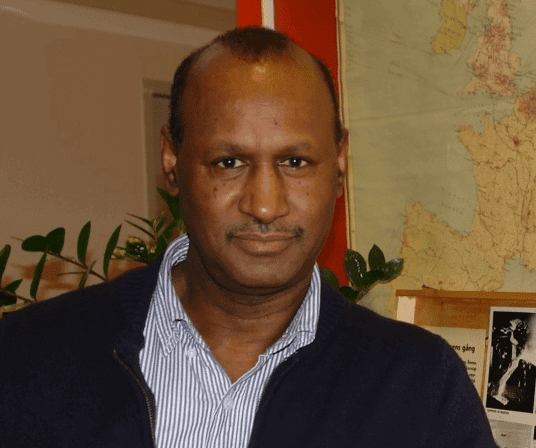

With Kenenisa Bekele, you never know what’s coming. Gone are the days when the Ethiopian ran the distance-running world like a dictator; the 39-year-old’s powers weakened by time, injuries, and an occasional lack of dedication to a craft he once perfected like no other.

Marathon world record-holder Eliud Kipchoge may be defined by his diligence and consistency, but in many ways, Bekele is the opposite. His performances can be utterly astounding or unexplainably poor. Depending on the time of year, he can be ruthlessly driven or hopelessly distracted. He runs with a heart of a warrior, the race craft of a champion, but has developed a habit of quitting if things aren’t going his way.

Bekele is flawed and sometimes flawless, human yet occasionally superhuman. He’s likely the best there’s ever been.

Bekele is flawed and sometimes flawless, human yet occasionally superhuman. He’s likely the best there’s ever been.

At the Berlin Marathon on Sunday, he’ll run his first race in more than 18 months, and as is so often the case with Bekele, no one knows what to expect. He might break the world record. He might drop out. That’s the beauty of watching him: he’s the Russian roulette of great runners.

At the Berlin Marathon on Sunday, he’ll run his first race in more than 18 months, and as is so often the case with Bekele, no one knows what to expect. He might break the world record. He might drop out. That’s the beauty of watching him: he’s the Russian roulette of great runners.

A month ago, a source close to Bekele said “something special is coming” in Berlin, given the way he was training in Addis Ababa in Ethiopia. If that’s true, it would mark an astonishing turnaround for the second-fastest marathoner in history, whose 2:01:41 at the 2019 Berlin Marathon was just two seconds shy of Eliud Kipchoge’s world record, set in Berlin in 2018.

It has not been a smooth year. At the press conference in Berlin on Friday, Bekele said he contracted COVID-19 “nine months ago,” and “it was a really tough time.”

He’s been racing at a world-class level for 20 years now, the latter part of his career pockmarked by multiple dropouts. Yet the 39-year-old feels he has plenty of miles left in his legs.

“I don’t feel my age,” he said. “It’s a good age for marathon.”

A fellow athlete said Bekele was unfit and several kilos over his usual weight when arriving in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, for a training camp in the summer. Yet no one can get fit quick quite like Bekele, who was in that same position in the summer of 2019 before he changed his diet, trained hard, and produced that astonishing run in Berlin.

“We estimate he’s around the shape of two years ago,” Jos Hermens, Bekele’s longtime manager, told Runner’s World earlier this week. “It could also be 2:03, it could also be something else.”

Bekele’s career stands alone for its success across various surfaces: Bekele has 11 world titles in cross country, five on the track, three Olympic golds, and is just two seconds behind Kipchoge on the marathon all-time list.

If he could get the world record, it would all but end the debate over the greatest distance runner in history. Hermens said that’s the goal that has rekindled Bekele’s fire in recent years, making his motivation “the best ever” at the age of 39. Yet Hermens also knows this sport and the odds Bekele is facing.

“We have to be fair, his last good [marathon] was two years ago,” he said. “His preparation was a little short, but he’s very, very serious. It’s Kenenisa Bekele, there’s only one Kenenisa. The motor is still a Ferrari. We just hope the chassis is holding together.”

Sunday’s race will mark the first leg of an ambitious fall double by Bekele; he will race the New York City Marathon just six weeks later on November 7. Racing two marathons six weeks apart is rare but not unheard of at the top level, but there’s method in what many might perceive as madness. One reason it’s achievable, according to Hermens, is the new era of super shoes.

“It’s not like five years ago when people were crippled getting on the podium,” he said. “Now people are recovering better.”

The idea to run both races came from Hermens and Bekele was on board, the reasons for it going back to what they learned during Bekele’s career: He needs races within sight to stay motivated in training.

From 2001 to 2008, Bekele ran the World Cross Country Championships every spring, an event he dominated like no one before. The heavy training he did for that each winter laid a huge aerobic foundation for success that followed on the track each summer, with Bekele virtually unbeatable between 2004 and 2008, setting 5,000-meter and 10,000-meter world records that stood for 16 and 15 years respectively before Uganda’s Joshua Cheptegei broke them last year.

But a bad ankle injury in the fall of 2008 meant Bekele bypassed the World Cross Country in 2009, though he recovered his fitness in time to win double gold on the track at that year’s World Championships in Berlin.

“He ran himself into shape and did the double and thought, ‘Okay, see, I don’t have to train so much in the winter,’” Hermens said. “But he forgot he did it on the base of 10 years of very hard training.”

Bekele never ran the World Cross Country after that and whether it was correlation or causation, he never hit the same level on the track.

His success brought him great wealth and Bekele became more involved in business, which took much time and energy away from training. When he had a goal in sight, Bekele trained hard. When it was far away, he grew distracted, meaning he was often playing catch-up with his training and eating habits before races.

“He regrets that he lost some precious years but now he’s incredibly motivated,” Hermens said. “When he was young, he was always talented and while he worked hard, it came kind of easy to him. He could win when not at 100 percent, and that was working against him in his later thinking.”

Earlier this year Bekele was overlooked for a place on the Ethiopian Olympic team, having failed to toe the line for a 35K trial race in May. He told Sports Illustrated it was a “stupid” decision.

“He’s extra keen to prove to the federation they made a mistake,” Hermens said. “Now he’s very focused, very motivated, very disciplined. He knows he doesn’t have that much time left but the next few years we expect him to do some really special things. That’s my feeling.”

On Sunday a trio of pacemakers will take Bekele to halfway in about 61 minutes—the exact pace has yet to be decided—with the weather conditions during the race looking calm and dry with temperatures (15-20°C/59-68°F) slightly warmer than optimal.

In preparation, Bekele has trained with different groups in Addis Ababa, though COVID-19 restrictions in Ethiopia meant he did much of his training alone over the past year.

“It was a really tough time for me, for everybody,” he said.

His lead coach Haji Adilo told Letsrun.com this week that his fitness is a “little bit better” than in 2019, and Bekele believes that race taught him exactly what is required to become the fastest man of all time.

“To follow the record pace that time I had a little bit of fear,” he said. “This time I have full confidence, I know how [painful] this is. I will try my best.”

How to watch the Berlin Marathon

The Berlin Marathon starts at 9:15 a.m. local time (3:15 a.m. ET) on Sunday, September 26. Viewers in the United States can watch live on NBC Sports from 3 a.m. until 6 a.m. ET.