Azmat Sadd Al-Nahda Al-Ethiopi (The Ethiopian Renaissance Dam Crisis) by Mohamed Nasr El-Din Allam, Dar Al-Mahroussa Publishing, Cairo, 2014. pp.242

The story of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, which Ethiopia has already started to construct, has a long history that dates back to the 1950s. Ethiopia has attempted many times to control the sources of the Nile — Egypt’s lifeline.

The book’s author is a former Egyptian minister of irrigation and water resources, who took office in 2009 in a decisive period in which Ethiopia attempted to build an alliance of upstream states against downstream states. The objective of this alliance was to breach the historic Nile treaties.

Certainly the author is not just an official running one of the oldest ministries in Egypt and the most bureaucratic, but he also has intimate knowledge of the minutest details of the issue. This issue is directly linked to Egyptian national security. It goes without saying that all documents, treaties, maps, data and agreements were at his disposal.

The reader is faced with a serious work that is technical and supported with accurate numbers. At the same time, he sets out a practical plan to confront future threats or at least minimise them.

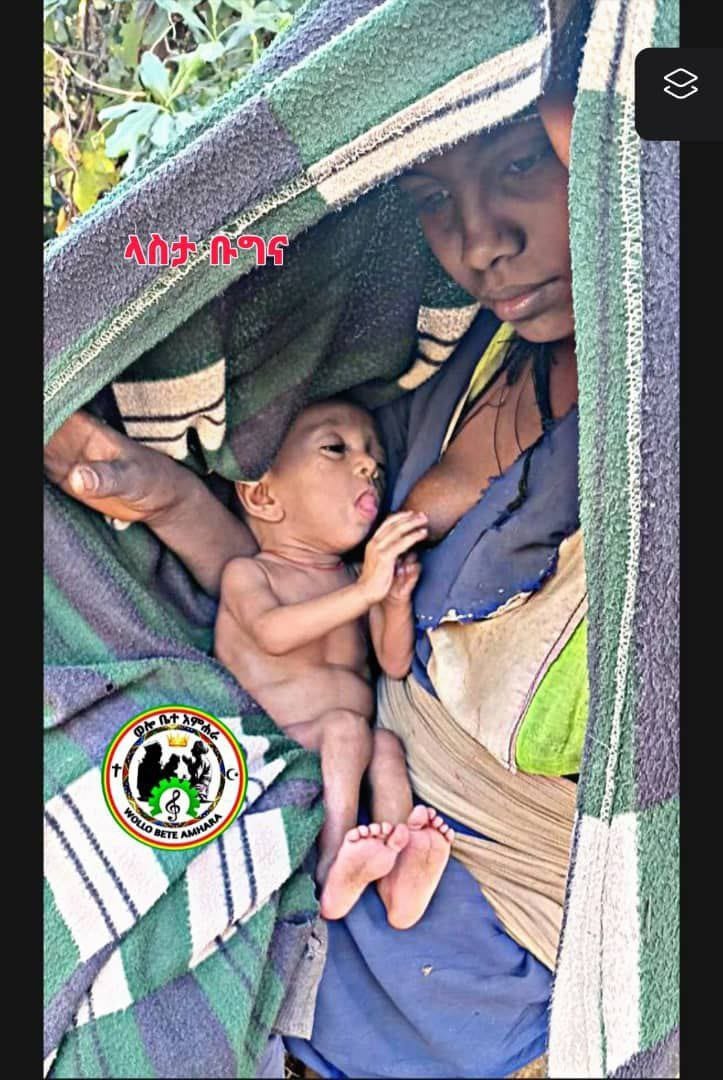

Egypt is facing a real water crisis because its Nile River quota has been almost fixed since 1959, while its water needs have multiplied due to its soaring population (26 million person in 1959 to 90 million person today), its agricultural area has expanded from under 6 million feddans to 8.4 feddans, while its industry has also grown and naturally all this has increased its demand for water.

Since the 1970s, water use has surpassed water resources every year. These deficits are managed by the state through recycling. The water situation is extremely perilous because Egypt gets 95 percent of its water needs from the Nile. Egypt gets its fixed annual quota of water according to a 1959 treaty with Sudan.

It is expected that the crisis will worsen in the near future because of the secession of South Sudan and the impact of this on Egypt’s water quota, and also because of the current approach of the Sudanese state based on distancing itself from Egypt and aligning with Ethiopia.

During the last two decades, Israel’s role became prominent once again, Somalia crumbled, Eritrea became independent, South Sudan became independent and Ethiopia and Uganda became rising regional powers. These two countries specifically played important roles in the region with support from the big Western powers.

In the fourth chapter, the author mentions that Ethiopia, in particular, submitted a legal complaint to the UN protesting the aforementioned 1959 treaty. Emperor Haile Selassie decided to sever the Ethiopian Church from the Egyptian Coptic Church after 1,600 years. In response to constructing the High Dam, the United States government sent a large mission from the American Bureau of Reclamation to Ethiopia to conduct a survey of the Blue Nile lands and construct a number of dams. Some of these were constructed without consulting the downstream states or even notifying them.

Dr Allam asserts that Ethiopia took advantage of the circumstances in Egypt after the January 2011 revolution to begin constructing the dam. International and Egyptian studies show the dam will make large agricultural areas barren, lower the groundwater table and cause negative effects on fish resources, Nile tourism, river transport and a huge decrease in electricity production coming from the High Dam and the Aswan Dam. In addition to this, it will shrink the role of the High Dam in protecting Egypt from famines and the ravages of the years of low flood. It will also result in environmental deterioration, pollution in northern lakes and seawater intrusion in the coastal aquifers. Moreover, Egypt and Sudan will suffer huge dangers if the Renaissance Dam crumbles.

From another perspective, the author sees the Renaissance Dam crisis as a political issue in the first place, which requires a speedy reaction from the Egyptian state in order to achieve a quantum leap in negotiations with the Ethiopian leadership. He suggests, for instance, achieving an immediate agreement on the formation of an international committee to examine the dangers of the Renaissance Dam while requesting a halt in construction activities during the experts’ study, which should not exceed six months, and reaching an agreement about a mechanism to resolve the dispute between the two states.

If such measures fail, Egypt will have no other choice but to file a complaint with the African Union or the UN Security Council or both. This step will internationalise the issue with all the unwanted consequences. Therefore it must be studied thoroughly. Anyway, the author suggests attempting to make Ethiopia agree to resort to either the International Court of Justice or the Arab League, African Union or the Security Council in order to remove the damage caused by constructing the dam, which threatens the regional and international peace and security.

Despite the fact that the author has vast and accurate knowledge in the field of the Nile and his personal awareness of Ethiopian policies, with American and Israeli backing, he does not point out the catastrophic errors of Hosni Mubarak’s regime in this context following the failed assassination attempt against him in Ethiopia in the 1990s. Egypt turned its back for two whole decades on Africa. It did not practise its historical role of preserving its national security through cooperation, understanding and support for the upstream states as Muhammad Ali Pasha did almost two centuries ago.

Source: Ahram Online