By Alex De Waal- BBC Africa analyst

January 2, 2021

The armed clashes along the border between Sudan and Ethiopia are the latest twist in a decades-old history of rivalry between the two countries, though it is rare for the two armies to fight one another directly over territory.

The immediate issue is a disputed area known as al-Fashaga, where the north-west of Ethiopia’s Amhara region meets Sudan’s breadbasket Gedaref state.

Although the approximate border between the two countries is well-known – travellers like to say that Ethiopia starts when the Sudanese plains give way to the first mountains – the exact boundary is rarely demarcated on the ground.

Colonial-era treaties

Borders in the Horn of Africa are fiercely disputed. Ethiopia fought a war with Somalia in 1977 over the disputed region of the Ogaden.

In 1998 it fought Eritrea over a small piece of contested land called Badme.

About 80,000 soldiers died in that war which led to deep bitterness between the countries, especially as Ethiopia refused to withdraw from Badme town even though the International Court of Justice awarded most of the territory to Eritrea.

It was reoccupied by Eritrean troops during the fighting in Tigray in November 2020.

After the 1998 war, Ethiopia and Sudan revived long-dormant talks to settle the exact location of their 744km-long (462 miles) boundary.

The most difficult area to resolve was Fashaga. According to the colonial-era treaties of 1902 and 1907, the international boundary runs to the east.

This means that the land belongs to Sudan – but Ethiopians had settled in the area and were cultivating there and paying their taxes to Ethiopian authorities.

‘Deal condemned as secret bargain’

Negotiations between the two governments reached a compromise in 2008. Ethiopia acknowledged the legal boundary but Sudan permitted the Ethiopians to continue living there undisturbed.

It was a classic case of a ‘soft border’ managed in a way that did not let the location of a ‘hard border’ disrupt the livelihoods of people in the border zone; there was coexistence for decades until just now, when a definitive sovereign line was demanded by Ethiopia.

The Ethiopian delegation to the talks that led to the 2008 compromise was headed by a senior official of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), Abay Tsehaye.

After the TPLF was removed from power in Ethiopia in 2018, ethnic Amhara leaders condemned the deal as a secret bargain and said they had not been properly consulted.

Each side has its own story of what sparked the clash in Fashaga. What happened next is not in dispute: the Sudanese army drove back the Ethiopians and forced the villagers to evacuate.

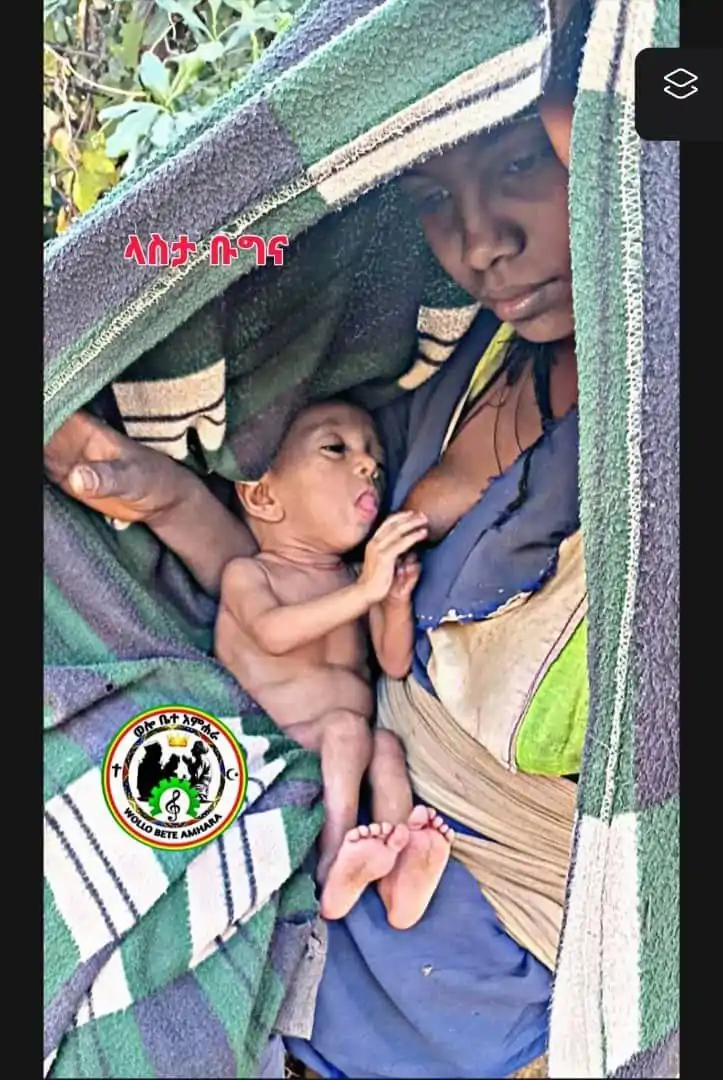

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESAt a regional summit in Djibouti on 20 December, Sudan’s Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok raised the matter with his Ethiopian counterpart Abiy Ahmed.

They agreed to negotiate, but each has different preconditions. Ethiopia wants the Sudanese to compensate the burned-out communities; Sudan wants a return to the status quo ante.

While the delegates were talking, there was a second clash, which the Sudanese have blamed on Ethiopian troops.

As with most border disputes, each side has a different analysis of history, law, and how to interpret century-old treaties. But it is also a symptom of two bigger issues – each of them unlocked by Mr Abiy’s policy changes.

Territorial claims in Tigray

The Ethiopians who inhabit Fashaga are ethnic Amhara – a constituency that Mr Abiy increasingly hitched his political wagon to after losing significant support in his Oromo ethnic group, the largest in Ethiopia. Amharas are the second largest group in Ethiopia and its historic rulers.

Emboldened by the federal army’s victories in the conflict against the TPLF over the last two months, the Amhara are making territorial claims in Tigray.

After the TPLF retreated, pursued by Amhara regional militia, they hoisted their flags and put up road signs that said “welcome to Amhara”. This was in lands claimed by Amhara state but allocated to Tigray in the 1990s when the TPLF was in power in Ethiopia.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESThe Fashaga conflict follows the same pattern of claiming sovereignty – except that it is not about Ethiopia’s internal boundaries, but the border with a neighbouring state.

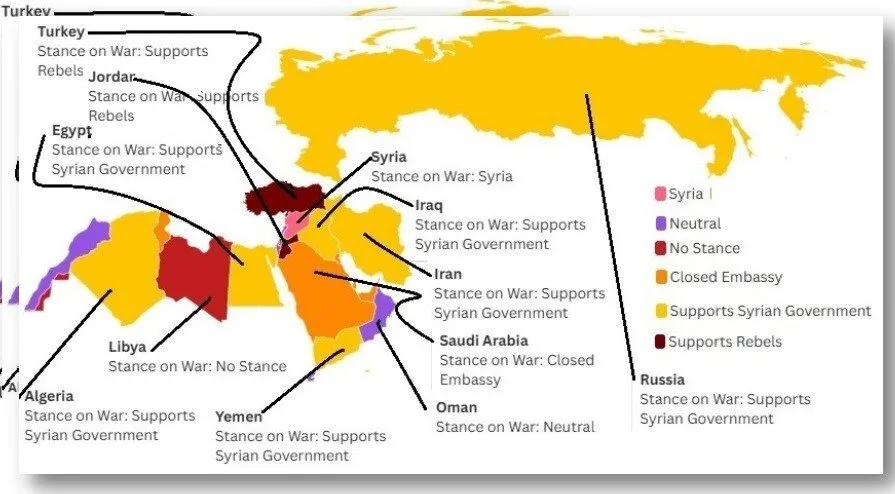

The failure to resolve it peacefully is the indirect result of another of Mr Abiy’s policy reversals: Ethiopia’s foreign relations. For 60 years, Ethiopia’s strategic aim was to contain Egypt, but a year ago Mr Abiy reached out a hand of friendship.

The two countries each regard the River Nile as an existential question.

Egypt sees upstream dams as a threat to its share of the Nile waters, established in colonial era treaties. Ethiopia sees the river as an essential source of hydroelectric power, needed for its economic development.

The dispute came to a head over the construction of the huge Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (Gerd).

The bedrock of the Ethiopian foreign ministry’s hydro-diplomacy used to be a web of alliances among the other upstream African countries.

The aim was to achieve a multi-country comprehensive agreement on sharing the Nile waters. In this forum, Egypt was outnumbered.

Sudan was in the African camp. It was set to gain from the Gerd, which would control flooding, increase irrigation, and provide cheaper electricity.

Egypt wanted straightforward bilateral talks with the aim of preserving its colonial-era entitlement to the majority of the Nile waters.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESIn October 2019, Mr Abiy flew to the Russia-Africa summit at Sochi. On the side-lines he met Egyptian President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi.

In a single meeting, with no foreign ministry officials present, Mr Abiy upended Ethiopia’s Nile waters strategy.

He agreed to Mr Sisi’s proposal that the US treasury should mediate the dispute on the Gerd. The US leaned towards Egypt.

If the young Ethiopian leader, who had just won the Nobel Peace Prize for ending tensions with Eritrea, thought he could also secure a deal with Egypt, he was wrong. The opposite happened: the 44-year-old cornered himself.

Sudan was the third country invited to negotiate in Washington DC. Vulnerable to US pressure because it desperately needed America to lift financial sanctions imposed when it wasdesignated a “state sponsor of terrorism” in 1993, Sudan fell in with the Egyptian position.![]()

Ethiopian public opinion turned against the American proposals and Mr Abiy was forced to reject them, after which the US suspended some aid to Ethiopia. US President Donald Trump warned that Egypt might “blow up” the dam, and Ethiopia declared a no-fly zone over the region where the dam is located.

‘Pattern of mutual destabilisation’

The Nobel laureate can ill-afford further disputes with Egypt, amidst the conflict in Tigray and the clashes in Fashaga. The latter raise the ghosts of a long history of rivalry between Ethiopia and Sudan.

In the 1980s, Communist Ethiopia armed Sudanese rebels while Sudan aided ethno-nationalist armed groups, including the TPLF. In the 1990s, Sudan supported militant Islamist groups while Ethiopia backed the Sudanese opposition.

With armed clashes and unrest in many parts of Ethiopia, and Sudan’s recent peace deal with rebels in Darfur and the Nuba Mountains still incomplete, each country could readily return to this age-old pattern of mutual destabilisation.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESRelations between Sudan and Ethiopia reached their warmest when Mr Abiy flew to Khartoum in June 2019 to encourage pro-democracy protesters and the Sudanese generals to come to agreement on a civilian government following the overthrow of long-term ruler Omar al-Bashir.

It was a characteristic Abiy initiative – high profile and wholly individual – and it needed formalization through the regional body Igad and the diplomatic heavy lifting of others, including the African Union, Arab countries, the US and UK to achieve results.

Sudan Prime Minister Hamdok has tried to return the favour by offering assistance in resolving Ethiopia’s conflict in Tigray. He was rebuffed, most recently at the 20 December summit, at which Mr Abiy insisted that the Ethiopian government would deal with its internal affairs on its own.

As refugees from Tigray continue to flood into Sudan, bringing with them stories of atrocities and hunger, the Ethiopian prime minister may find it more difficult to reject mediation.

He also risks igniting a new round of cross-border antagonism between Ethiopia and Sudan, deepening the crisis in the region.

Alex De Waal is the executive director of the World Peace Foundation at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University in the US.