AWOL ALLO and ABADIR M. IBRAHIM 23 October 2012

(Open Democracy) — From the periphery, Ethiopian Muslim protesters have recently turned a page in the history of the country. They have proven that demonstrations by religious groups can be peaceful, that secularism can be the aim of these groups instead of their nemesis and that a radical Islamist agenda doesn’t have to be the dominant one.

——————————————————————————–

The early contact between Ethiopia and Islam is romantic. It begins in the days when Islam was a new religion in Arabia and Muslims a persecuted minority. When persecution by their Arab kin became unbearable, early Muslim converts sought and were granted refuge by an ancient Ethiopian-Christian King, an asylum that is depicted spectacularly in Islamic theological history. For centuries to come, when Islamic conquest was expanding in the region and beyond, the Muslim Caliphs returned the favour by not invading the Ethiopian-Christian kingdom in accordance with the prophet’s order to “leave the Ethiopians alone”. After a millennium and a half, the two, conjoined in this unique way, may be on the verge of a monumental turning point in their common history.

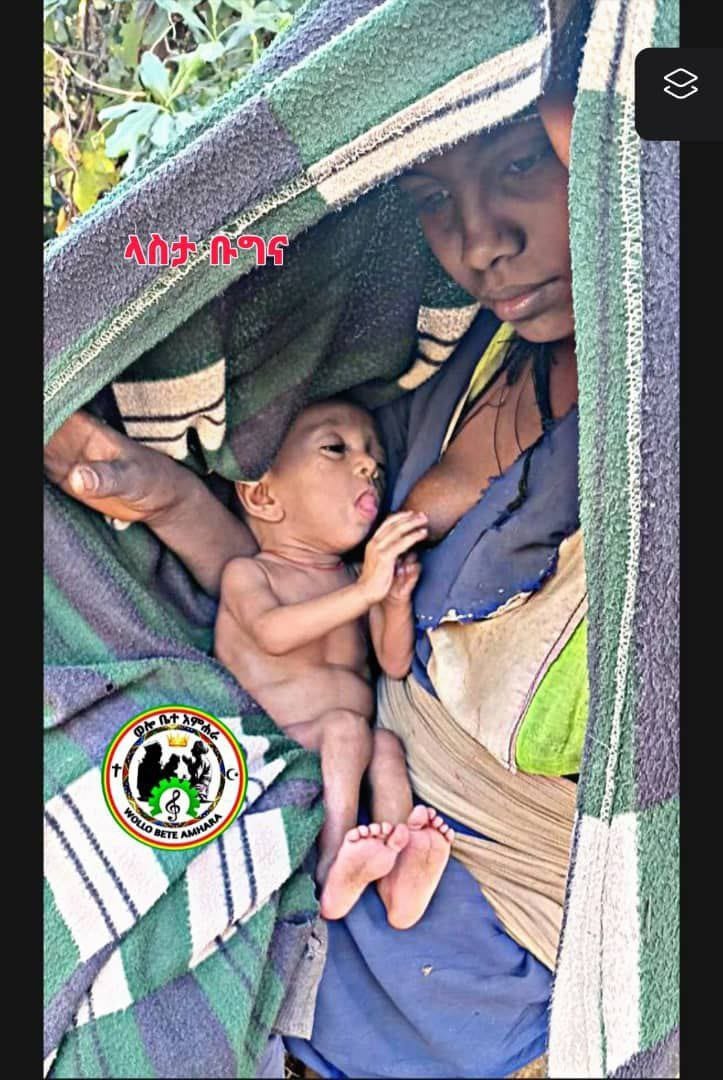

While the romanticized relationship would not last. Muslim Caliphates and Emirates later made numerous attempts at invading the Christian Kingdom only to be halted by the latter. The Empire would also begin persecuting, forcefully baptizing and even, at times, massacring its Muslim minority. As late as the 1980s, when they probably constituted the largest demographic block, Ethiopian Muslims were treated as foreigners in their own country. Ironically it was a Marxist Leninist dictatorship, responsible for the end of imperial rule in the country, which finally established religious equality and secularism. Today, four decades later, formal equality still persists. However, the Orthodox Christian community still represents the socio-cultural mainstream; a situation that leads many Muslims to conceive themselves as inhabiting the periphery on the Ethiopian political map and social ethos.

Even though the principles of freedom of religion, equality and secularism have now been entrenched in its constitution, Ethiopia is far from realizing these ideals. Recently, the state media has been accusing ‘elements’ in the Muslim population of conspiring to commit crimes including terrorism and mass violence. At the same time, voices within the Muslim community, mainly through social media and peaceful protest, have been accusing the state of hijacking Muslim organizations nationwide and introducing and forcefully promoting a new sect in the name of fighting Islamic extremism.

Out of this battle a number of fascinating trends are emerging. In most of the Middle East, Muslims have generally tended to advocate for some form of state recognition of religion or even theocracy, but the Ethiopian Muslim movement is pushing for a secular state. For the first time in the country’s history, also, an organized non-violent protest has been launched. Unlike in the past, the most important political initiative is coming not from the centre but from the periphery, from the Muslim population of Ethiopia.

The Majlis: where the trouble started

At the centre of the controversy lies the institution that is supposedly representative of the Muslim population in Ethiopia: the Ethiopian Islamic Affairs Supreme Council (popularly known as the “Majlis”). Although there seems to be a popular consensus regarding the need for an institution of its ilk, the institution has a dark political history and a dubious legal basis. The Majlis was established by the Marxist-Leninist military regime in solidarity with the urban Muslim population who supported the revolution that led to the downfall of the Orthodox-Christian imperial regime. Unlike other religious organizations, however, the Majlis was not established by or through law; it was established simply because it was willed by a handful of Muslims and the military elite in the capital, Addis Ababa.

After the fall of the military regime, the Majlis’ legal status changed, though its precarious legal identity remained. Established as a non-profit and non-political body corporate, the Majlis now functions more like an administrative-executive arm of the state that not only professes to represent but also regulate the Muslim community and its faith. Every year, together with the leaders of the Catholic, Orthodox and Protestant Churches, the head of the Majlis makes televised public statements on national holidays. But akin to the executive branch of the state, and unlike the other religious bodies, it has additional extra-legal powers. One of these is its de facto power to veto the registration and licensing of any Islamic/Muslim organizations in the country, which means that a legally registered Muslim non-governmental organization or association can be shut down by the Majlis’ orders. Another significant governmental power arrogated to Majlis’ concerns is its regulatory power over issues of visa and travel to Hajj (Muslim pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia). An Ethiopian Muslim going on pilgrimage should get her travel documents and even her air ticket through the Majlis, which charges exorbitant fees and inflated travel costs. Thus, without any legal basis, the organization exercises the power of representation, correspondence, diplomacy and even public administration, and all this in the name of Ethiopian Muslims.

As a de facto organization that is recognized and legitimized by the state, the Majlis has also been able toflout regulatory rules applicable to non-governmental organizations such as licensing, renewal and annual audit reports. The sheer amount of power the Majlis wields is certainly no accident. It exists in a symbiotic relationship with the state whereby it provides control over major mosques, charities and the ‘Muslim voice’. In return, the state provides tenure to its leaders who are taken care of relatively reasonably for occupying formally ‘unpaid’ posts and tolerates the de facto administrative/executive powers that the institution and its leaders have come to enjoy. From the perspective of Muslims, this arrangement is tolerated mainly because the Majlis stands for the idea that Muslims have an organization that represents them on a par with the historically influential Orthodox Christian Church.

Maintaining a delicate balance between right to religion, secularism and political expediency

The Majlis’ operation outside the bounds of the written laws can be partially explained by the precarious type of secularism practiced in the country whereby the state is not explicitly religious but tightly controls religious establishments. This it does without any explicit or implicit authority of the written law. The state’s hegemony over the Majlis, or other religious organizations, has however never gone unchallenged as the community of believers wrestles for and seesaws over control. For most of the last two decades, some mutually tolerable balance was maintained with the right hand always on the side of the state.

This balance was recently disrupted when the state decided essentially to launch a sectarian conflict and weigh in on the side of the underdog that the state had introduced. Prompted by the expansion of Wahabi/Salafi trends in Ethiopia and the neighbouring countries and a spike in inter-religious civil clashes, the state took matters a step farther when it decided to import a new and presumably more peaceful and tolerant Islamic sect from Lebanon under its protection. The followers of the sect, who are primarily Lebanese, are known as the “Ahbash” (trans. “the Ethiopians/Abyssinians”), a reference to its now deceased Ethiopian leader who rose to this rank being exiled to Beirut. Before its state-sponsored introduction, the Ahbash sect did not have more than a dozen or two followers in Ethiopia. Given the capacity of this third world state, struggling to implement even mundane administrative tasks, this was an piece of adventurism destined to fail.

According to the US State Department Terrorism Report, Ethiopia’s Ministry of Federal Affairs launched a nation-wide training in July 2011 to train Imams and Quranic scholars throughout the country. In an article published in Foreign Policy, Mohammed Ademo identifies the trainers as Lebanese Ahbash scholars, confirming the protestor’s claim that the state is undertaking a mass Ahbashization of Ethiopian muslims. The training included both theology and political indoctrination in which mosque leaders and scholars were introduced to Ethiopia’s “revolutionary democracy” as a unique and superior existing system of governance which would guarantee the country’s ‘continued’ political and economic salvation. It looks like the eventual plan was to marginalize or get rid of other sects seen as politically or ideologically hostile to the regime from positions of influence by assigning these scholars as Imams to mosques all over the country.

This was not only a disturbance of the already illegal but delicate balance, but was a clear and escalated violation of the country’s constitution and its international human rights obligations. It was also clumsy in its implementation. The state’s actions including videos of high state officials proclaiming their plot to introduce the new sect flooded the social media. Soon enough, an overwhelming majority of the Muslim population opposed the intervention and rejected the new sect’s doctrines before the latter even reached the market place of ideas. In the end, the fight was not one of theology but of constitutional principle; it was to turn into a genuine struggle by a religious community for a secular state.

Given the history of the nation and the delicate balance in place, the state should have expected that such an overt intervention would not go down well with the majority of Muslims who already think that the state interferes too much in their organization and the public expression of their faith. As the regime begun deploying trained al-Ahbash preachers into mosques and religious schools throughout the country, coercing mosque leaders to cooperate with the new scholars, there emerged a wave of small-scale protests across the country. While the overarching question that animates the life of the protest is the demand for religious freedom, an irreducible political demand lies at its core. Insofar as they are demanding an end to state interference in religious affairs, theirs is a demand for secularism born out of the recognition that the realm of the divine is constitutionally excluded from the dominion of the state. It is a protest against the political use of an institution that supposedly represents and speaks on behalf Muslims but does not really represent them in any meaningful sense of the term.

During a question and answer session in Parliament, the late Prime Minister Meles Zenawi provided the ideological-political framework for the on-going Ahbash debacle. Zenawi denounced the protest, blaming and dismissing the protesters’ demands as an orchestration of violence by “extremist Salafi elements”. The Prime Minister situated the threat posed by ‘Salafi’ ideology within the broader geopolitics of the region. In that same speech, Zenawi drew connections between Salafi ideological proximity to al-Qaeda, its destabilizing role in neighbouring Somalia, and the broader war on terror. Exaggerating the imminence of the threat presented by the movement, in order to favour the supposed moderates, he pointed to two specific sites in Ethiopia—Bale and Arsi—where he said a Salafi cell has been uncovered.

In a nation where there are no vacancies for fact-checkers, Zenawi knew that no one could call him out on specifics. Whatever the facts, Zenawi’s statements had the effect of establishing a hinge between the protest and al-Qaeda, via the “extremist Salafi elements” deemed responsible for orchestrating the protest. His statements were intended to instil fear, a red hysteria that would, in one and the same move, coerce ordinary Ethiopians into submission and prepare them for an inevitable crackdown. In so doing, the late Prime Minister created the framework for interpreting the demands of Ethiopia’s Muslim community: protest-violence-al-Qaeda. Accordingly, the security forces violently crushed protests and arrested several leaders of the movement on a charge of terrorism.

In the following months, the state media, the sole source of information in a nation of close to 90 million, began to demonize protesters and their leaders, blaming them for violence and accusing them of ‘terrorism’; a ready term for callously labelling opposition groups, local and foreign journalists, and political activists. As usual, the state-owned media in Ethiopia helped to eradicate the very condition of visibility and audibility of bodies and voices that speak from the political periphery.

These voices were deemed threats even before being heard, to the very cohesion of the nation. The media began framing the issues as sectarian, an intra-Muslim conflict. The legitimate political and legal claims of the protestors were twisted, distorted and equated with violence. On the other hand, the violence and direct political involvement of the state was defined as the protection of “law and order”.

Framing violence and the leap towards a new culture of protest

The Ethiopian Television Station (ETV), the only TV station in the nation, plays a crucial role of inexorably mapping events into readily available frameworks of meaning and interpretation, always attentive to the geopolitics of the region, and differentially oriented to local and global audiences. In the context of this movement, this has meant raising the specter of Islamic terrorism in ways that are politically productive both within and outside. Internally, Ethiopian Christians and Muslims must feel threatened by the new development, framed as the rise of Islamic extremism in their country. Ethiopian Muslims must be cautioned about taking part in any protest lest they should face a wrath fitting only to terrorists. Party ideologues and cadres are to take their cues from the media not only to begin identifying terrorists but to begin talking to the Muslim population, calling meetings, and identifying those who need to be cleansed of political/ideological deviation if they are to be brought back to a politically righteous path.

Externally, western powers will ‘recognize’ the magnitude of the danger threatening Ethiopia, so that they will tolerate the transient repression as necessary and proportionate to the threat. Without naming names and explicitly referring to the protesters and their leaders as terrorists, this conjures up an image of the movement and the leaders that exhibits characteristic features of “the war on terror”. This is a tactic that amply prepares the body politic for the ultimate political judgments of the state if the protesters refuse to accept the terms put forth by the state.

Once the stage is set by the media machine, the next step is clear and predictable. Despite the huge turnout and uncompromisingly peaceful expression of their grievances, the media portrayed the protesters, predictably, as violent extremists, and ultimately terrorists. In order for this frame of violence to perform the much anticipated political task, there has to be actual episodes of confrontation where protestors will be conveniently televised throwing stones, breaking windows, and setting public and private property on fire. This, in effect, would allow the state to intervene in the name of law and order, violently crush the protest, arrest activists, and prosecute them under one of a range of grotesque laws.

However, no one really expected what followed. The arrests were made, guns fired, protesters hospitalized, eyes and lungs swollen from tear gas exposure. The protesters however, did not reciprocate in kind. Instead of harnessing them into violence, the media framing of the protest and the violence of the state transformed what was a dispersed and localized micro-protest into an exemplary nation-wide movement. Exemplary because of its innovative mode of resistance, its ability to introduce new genres of protest that did not exist on the Ethiopian political map, because of its impeccable rejection of violence as a means, its ability to anticipate, decipher and detect multiple repressive techniques of the state, and because it established itself as disciplined and peaceful.

In adhering to non-violent modes of protest, they not only disrupted the state’s narrative of violence and terrorism, but also denied the state the very weapon upon which it thrives, that crucial hinge that connects the movement to the discourse of terrorism—violence. By refusing to throw stones at public properties, even when the state made public resources such as city buses available in the vicinity of the protest, the movement established itself as anything but violent. Outwitting alleged agent-provocateurs and coordinating through whatever resources available, they disrupted the image of violence the state and the media were busy painting.

By emphasizing the peaceful nature of their demands, the protesters turned to known signs and symbols of peace during protests. Exposing the media’s anticipation of violence as a trick that power uses to lure its subjects, they not only tried to hold on to the core political contents of their protest but also sought to retrieve what had already been usurped, and demanded a hearing for their voice and visibility for their image. By attending to the mediating power of the media, they resisted, if not sufficiently subverted, the violence into which the regime was luring them, and galvanized solidarity from those supposed to be afraid of their extremist aims, namely, Ethiopian Christians.

The unique and appealing secret of this protest lay in a text that is amenable to different interpretations. This protest may not be as captivating as the confrontation between that lone Chinese student and the tank at the Tiananmen Square, but it captures the mis-en-scene of many forms of contemporary protests that must craft strategies local to their circumstances in order to avoid their cooption and re-appropriation by the state. In demanding their constitutional rights, the protestors affirm that they are not revolutionaries. The protestors’ chant, in Arabic – “the people want to bring down the Ahbash/Majlis” – is taken word for word from that of the Arab Spring, except that the Arab Spring revolutionaries had a far wider mission.

In seeking respect for the principle of secularism, strict separation between Church and the State, they draw on enlightenment rationality. They also employ theological and subversive genres—subversive in the postmodernist sense of the term. They chant ‘Allahu Akbar!! [God is great], they carry the white ribbon, and appropriate non-verbal modes of expression to expose and counter the narrative of the state.. Insofar as terrorism figures as a significant trope in the strategy of the state, the protestor’s strategy aims at ‘disruption’ i.e., disrupting the state’s narrative of violence and terrorism, and therefore denying it the very weapon it needs to justify its own violence against protesters.

There’s light at the end of the tunnel, and some crocodiles too

Having arrested key leaders of the movement, the state held long-awaited elections on 7 October 2012. The protesters continued to vehemently oppose the government’s decision to go forward with the election while representatives of the protest remained in jail. They quickly rejected the outcome of the election as a sham and continued to call on the state to respect the fundamental constitutional premise on the separation of state and religion. In his first address to the Parliament, the new Prime Minister, Hailemariam Desalegn congratulated the Muslim community for conducting what he described as a ‘free and democratic’ election and reiterated his commitment to the policies of his predecessor. In a move reminiscent of Meles Zenawi, Desalegn raised the spectre of terrorism as a scare tactic.

For the first time in the country’s history, a solely non-violent culture of protest seems to be taking shape. But non-violent action is an undertaking that is fraught with risks and its success requires consistency, persistence and a creative genius capable of adapting to different situations thrown against it by its Goliathan protagonist. Independently and/or despite the best efforts of its organizers, the protests can also either run out of steam or turn violent. If the protests turn violent or a section within it resorts to violence, not only would the non-violent movement fail but would also fail in its pioneering identity. In the event that the state turns to violence while all involved remain peaceful, the protest will probably retain its pioneering legacy.

Things are moving quickly and they are moving from bad to worse. On 20 October 2012, the state media reported the death of two protestors and a policeman in the northern part of the country. While the protestors have fully embraced a peaceful and non-violent means of expressing their grievances, violence seems to be the inevitable expression of law and order on the Ethiopian political landscape. Unless both the state and the protesters act with the maximum possible restraint and diligence in the lead up to the forthcoming Muslim holiday of Hajj, things might spiral out of control. Tension is already running high. In a country where protest is de facto criminalized, the holiday is an event of a very high political significance. It will be used as an opportunity for the protestors to demonstrate that the October 7 election was indeed a sham, fraudulent and staged exercise by the state. Equally, the government wants to repress and contain any rupture that might escape its control. The protestors have already given a yellow card to the government. If the standoff continues to drag on, there is the risk of political outsiders who have nothing to lose and everything to gain from the escalation of the confrontation. In the end, if the protesters succeed in retaining what is so unique about this protest, they will have set an exemplary precedent in the nation’s history of protest and political activism, irrespective of its material outcome.

About the authors

Abadir M. Ibrahim is a J.S.D. Candidate at St. Thomas University Law School. Previously, he has been a federal public prosecutor at the Ethiopian Ministry of Justice and held adjunct positions teaching law at Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Awol Allo is the Lord Kelvin/Adam Smith Scholar at the University of Glasgow Law School, Glasgow, UK. Previously, Awol was a lecturer at St. Mary’s University College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.